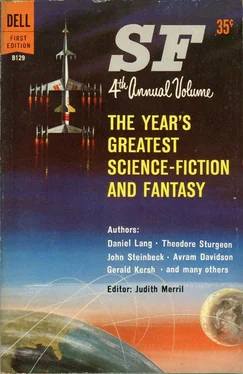

Judith Merril - The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Judith Merril - The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1959, Издательство: Dell, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell

- Жанр:

- Год:1959

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Man’s age-old physical and psychological needs and frailties, it seems—”the human factors,” as man-in-space experts call them—make him a rather poor risk for space voyaging, and some of the scientists I have talked to, or whose treatises I have read, have expressed mild disappointment with man for not coming up to the astronautical mark. “Man’s functional system cannot be fooled by gimmicks and gadgets,” a comprehensive report on space flight got up for the Air University Command and Staff School, in Alabama, remarks. “He cannot be altered dimensionally, biologically or chemically. None of the conditions necessary to sustain his life-cycle functions can be compromised to any great extent.” Wherever man is and whatever his circumstances, the report says, in effect, he simply must have many of the things that sustain him here below—air, food, and a certain amount of intellectual and physical activity. “Encapsulated atmosphere is what we’re after,” one scientist told me, and went on to explain that the space traveler— whether wearing a space suit in an airless cabin or, as most scientists would prefer, wearing ordinary clothes in a pressurized cabin—would have to have enough of the familiar earthly environment to see him through his voyage. “A spaceship,” this scientist said, “must, you see, be a ‘terrella,’ a little earth.”

The human factors in space travel are being studied on a broad front, and at every level from the immediately practical to the highly theoretical, by special groups set up within our armed services, universities, and private aircraft companies—groups like the Space Biology Branch of the Air Force Aero Medical Field Laboratory, in Alamogordo, New Mexico, and the Human Factors Engineering Group of the Convair Division of General Dynamics Corporation, in San Diego, California. The assignments these groups have taken on are myriad, and practically every one of them necessarily involves guesswork, or what one man calls “the vagueness of imagination,” to a degree that most scientists abhor. Nonetheless, the job is being tackled, in its various aspects, by biochemists (who are concerned with the space traveler’s physical care and feeding), radiobiologists (who worry about the effects of cosmic rays in outer space), sanitary engineers (who are figuring out how to dispose of wastes and insure the cleanliness of the terrella), anthropometrists (who measure the functional capacities of man), astrobotanists (who are attempting to discover what sort of food, if any, the space man might find on other celestial bodies), and psychologists (who tend to doubt whether a man can roam extraterrestrially for years, months, or even weeks without going batty). Physiologists, chemists, pharmacologists, physicists, and astronomers are also making contributions to the man-in-space program, as are sociologists, whose responsibilities would seem to be remote at the moment but who foresee all kinds of catastrophic dilemmas in the future. “What will happen to a man’s wife and children when he embarks on a prolonged space trip, perhaps for years, with every chance of not returning?” one scholar asked not long ago, in a symposium called “Man in Space: A Tool and Program for the Study of Social Change,” which was held in the sober halls of the New York Academy of Sciences. “How long a separation in space would justify divorce, and if he should return, how will the [possible] Enoch Arden triangle be handled?” At the same symposium, Professor Harold D. Lasswell, of the Yale Department of Political Science, envisioned an even more drastic jolting of the status quo. He asked his learned audience to imagine what might happen if a spaceship’s crew landed on a celestial body whose inhabitants were not only more than a match for us technologically but had created a more peaceable political and social order. “Assume,” he said, “that the explorers are convinced of the stability and decency of the . . . system of public order that exists alongside superlative achievements in science and engineering. Suppose that they are convinced of the militaristic disunity and scientific backwardness of earth. Is it not conceivable that the members of the expedition will voluntarily assist in a police action to conquer and unify earth as a probationary colony of the new order?”

Before the space traveler can return to earth, with or without a police force at his back, he must go into space, and psychologists are now engaged in a sharp debate as to just what type of person would be best suited to embark on a long extraterrestrial trip. Addressing a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Indianapolis a few months ago, Dr. Donald N. Michael, a psychologist who has been doing research on the effects of automation, estimated that a journey to Mars might take about two and a half years, and concluded that our culture was unlikely to produce anyone with that much patience; good space men, he said, might be found in “cultures less time-oriented and more sedentary”—in a Buddhist monastery, perhaps, or among the Eskimos. Reasoning along other lines, Dr. Philip Solomon, chief psychiatrist at the Boston City Hospital, has come out for extrovert space voyagers. Like other medical men in all parts of the country, Dr. Solomon has been conducting what are called “sensory-deprivation experiments”—specifically, confining volunteers of various personality types in iron lungs to see how they bear up in isolation—and in a recent issue of Research Reviews, a monthly put out by the Office of Naval Research, he writes: “It appears that the self-centered introvert, whom you might expect to be quite content in the respirator, holed up in his own little world, so to speak, is precisely the one who breaks down soonest; whereas the extrovert, who is more strongly oriented to people and the outside world, can stand being shut off, if he has to, more readily. Sensory deprivation places a strain on the individual’s hold on external reality, and it may be that those who are jeopardized most by it are those whose ties to reality are weakest.”

Women have notoriously strong ties to reality, and for this reason, among others, some experts are convinced that they would fare better than men on a pioneering journey through space in cramped quarters. Another reason is that women live longer than men, and some of the envisioned journeys would take an extended period of time; still another is that women could probably weather long periods of loneliness better, because they are more content to while away the hours dwelling on trivia. Writing in the American Psychologist a couple of months ago, Dr. Harold B. Pepinsky, a psychology professor at Ohio State University, came up with the notion that the ideal space voyager would be a female midget with a Ph.D. in physics. When I asked a physiologist what he thought of this idea, he not only supported it heartily but embellished it. “It would be good if this midget woman Ph.D. came from the Andes,” he said. “We’re going to have to duplicate the traveler’s normal atmosphere in the ship, and it’s easier to duplicate a rarefied fourteen-thousand-foot atmosphere than a dense sea-level atmosphere.” The cards, though, seem to be stacked against any woman’s blasting off ahead of a man. One important officer, Lieutenant Colonel George R. Steinkamp, of the Space Medicine Division at the Air Force School of Aviation Medicine, in San Antonio, Texas, said recently, “It’s just plain not American. We put women on a pedestal, and they belong there.” The pedestal apparently should be anchored firmly to the ground.

As for the Ph.D. in physics, I gathered that while it would definitely be an asset, some of the experts are worried lest a physicist might not know all he should about astronomy. An astronomer, on the other hand, might be weak in meteorology, and a meteorologist might well bungle some vital engineering problem. An engineer might know how to operate and maintain his ship but would probably not be able to cope with any illness that happened to befall him. The possibility of illness in outer space is receiving its share of attention, to judge by a paper that Drs. Donald W. Conover and Eugenia Kemp, of Convair’s Human Factors Engineering Group, submitted to the American Rocket Society several months ago, in Los Angeles. “Space men and women must have almost perfect health in order to avoid bringing disaster on the flight by physical incapacity,” they declared, and went on to say that even these paragons of fitness should “be trained in self-medication and, particularly, the use of antibiotics.” From that point of view, the ideal traveler would seem to be a physician, but Professor Lasswell, the Yale political scientist, has a different idea. An anthropologist-linguist, he feels, would make a good space traveler, especially when it came to communicating with the inhabitants of remote celestial bodies; other candidates the Professor has nominated include individuals gifted with extrasensory perception—perhaps members of the Society for Psychical Research, Western parapsychologists, or Eastern mystics.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.