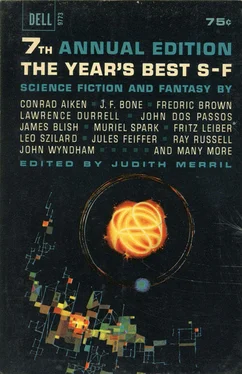

Judith Merril - The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Judith Merril - The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1963, Издательство: Dell, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell

- Жанр:

- Год:1963

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Of course, he has some special advantages. Possibly, this story could only have been written by an author who is both architect (by training) and anatomist (lecturer on, at the Art Students’ League) as well as a painter and poet of some years’ standing, and an editor, writer, and teacher of art. (Among other things, Curator of American Painting and Sculpture at New York’s Metropolitan Museum.)

Let me tell you about a dream I had and what happened afterward, because I think it all adds up.

You see, when this poet turned up a while back telling me he could live upstairs because Mrs. Stettheimer had said he could, there wasn’t much I could do. After all, Mr. Stettheimer had let us have the place free, as long as I painted him one picture a year. And upstairs wasn’t much anyway: it was where they used to keep the hay. There was an old sofa up there full of moths, and we gave him a blanket. He didn’t need a table, he said, because he never wrote anything down, he was extemporaneous. His name was Virgil Cranbrook; he came from Taos and San Francisco.

He wasn’t much trouble in the beginning. Mornings, Olivia used to pound on the ceiling with a mop handle and wake him up. Soon he would open the trap door, call for the stepladder and join us at breakfast. He took mescaline, or peyote, the drug that Huxley wrote about. He’d picked a supply of peyote buds near Taos and carried them around in his pockets. Every now and then he’d slice some with a razor blade, toast them in our toaster, and crumble them into powder. He’d put this powder in a jar of instant coffee, shake it up, and then at breakfast drink a couple of cups. After breakfast he would go upstairs and walk back and forth being extemporaneous.

The trouble was the moths up there couldn’t get used to him. He disturbed them. They’d crawl through the cracks in the ceiling and fly around my studio. Once so many of them got on a wet canvas of mine that they ruined it. I complained to Olivia, so she bought some moth balls and put them around upstairs. She also persuaded Virgil to carry some in his pockets along with the peyote buds.

Let me explain about Olivia. Thelonious Monk was playing at the Jazz Gallery one evening, and I found her next to me in the balcony. She had blank gray eyes, a thin body, and rather fat arms and legs. She wasn’t very attractive, but then I’m afraid I’m not either — and so far I haven’t been very successful. So we worked out an arrangement. She kept house well enough for me, and the nice thing about her was you didn’t know she was around when she was around.

The first thing that made me suspect there was something up between Virgil and Olivia were those whistles. Olivia and Virgil used to like to go to the beach, and one day they came back with a couple of tin whistles they’d found near some empty packages of Cracker Jack. Then they worked up a kind of game in the woods behind my studio — they’d separate from each other and start blowing the whistles. Ultimately they’d find each other and stop blowing. This used to go on while I was painting.

One morning Virgil came down to breakfast as usual, but after breakfast he didn’t go up again; he started declaiming right there — some crazy poem about what sex was like in outer space. Olivia sat on the bed and watched him. She was showing, I thought, a little too much appreciation. For me, this went on too long, so I told him to go upstairs or keep quiet; I wanted to paint. Since he wouldn’t pay any attention, I picked him up and threw him out the door. This wasn’t very hard to do because his co-ordination had been all shaken up by his morning coffee. Nevertheless, I handled him pretty roughly; he lost a couple of moth balls. Olivia looked irritated. I told them they could go out in the woods and blow their damn whistles, then slammed the door on both of them.

Right away they threw this stone, or rock, I guess you might call it, through the studio window. Outside, I heard them start up my car and head down the road.

Virgil’s special brew was still on the table. I mixed up a cup and poured in a lot of sugar. It wasn’t too bad. I drank three cups altogether. Soon I began to feel uneasy and lay down on the bed.

Outside the hole in the studio window, climbing up my rose bush, was a morning-glory vine. The blossoms were a very effective blue. On the floor a square of sunlight was making up into a nice arrangement with the rock they’d thrown through the window. As the sun moved across the floor, it occurred to me that the rock was not an ordinary Long Island rock. Long Island rocks look like Long Island potatoes, but this rock was a deep black, a real ivory black, and it had metallic flecks in it. I got off the bed, though it took a great deal of effort, and picked the rock up. It was terribly heavy for its size and roughly conical in shape— altogether, it had a lot of style. I decided I’d give it to Zogstein. He’d been making some very nice things out of iron lately, with a rock in the middle.

There came a loud knock, so I put the rock on the bed and opened the door. On the doorstep was a tall man carrying an open can of beer in one hand and a live lobster in the other. At first I thought he was an artist, because he hadn’t shaved and his shirt was such a tasteful, faded blue. But he didn’t have that troubled look, he had a general air of assurance; I decided he was a native of the place.

“Morning,” he said. “Got any pictures you want to trade?”

I understood the situation immediately. Jackson Pollock had come to Springs in 1947, and very shortly a number of other Abstract Expressionists, who are now famous, had followed him. Things were not so good in those days, so the grocer had occasionally let them exchange paintings for groceries. Lately, the grocer had been written up in Life magazine as a great collector, and had sold his Pollock for a price that had increased at every telling.

“I’m Lester Barnes, from over at Louse Point,” said the man at my door. “I’m putting up a little mess of drawings. They come cheaper than the big stuff, and I figure, I figure—” He seemed confused, and took a gulp of beer. “I figure that, well…”

“You mean that though they’re sort of small they still carry the personality of the artist?”

“Yep!” exclaimed Mr. Barnes enthusiastically. “That’s just what I mean. Now I’ve just been over to Mike Goldfarb’s. He gave me a drawing for seven lobsters. But I figured that after that panning you got in Art News you might let me have one for three.”

I didn’t like this much.

“All right,” I said.

“Here’s one down.” Mr. Barnes handed me the lobster. “I’ll bring the other two later.” He started down the path, hesitated, and came back. “The one I gave you — maybe you won’t eat him right away.”

“Why not?”

“Well, you see—” He took another gulp of beer and looked down at the ground. “You see, we’ve had him for quite a while. You might call him sort of a household pet. He’s even learned to play marbles with the kids.”

I took the lobster inside and put him down in the square of sunlight. He crawled across the room right away and went under the bed. That was all right, because it left the floor clear for me to do a little painting. I was feeling much better and was beginning to have ideas. Art News had said that my work was too busy, too many things in it. I decided I’d try for a very simple statement. Just two strong forms, one geometrical and one amorphous: And just two colors playing against each other, but strong ones.

I placed a forty-eight-by-fifty canvas on the floor, mixed up some vermilion, and painted in a nice round disc up near the top of the canvas. Then I got a can of ivory black and poured some out in a little pool down near the bottom.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.