The baby lost interest and went to wade in the stream but Adam watched, his elbow on his knee, and once he said, “Don’t crush the blackberries,” and reached out to get them. He ate a handful, slowly.

Then he heard his mother gasp, “Oh, praise God!” and after a moment both his parents became still. And after a little while longer he looked to see that the baby was okay and then went to the intertwined, gently-breathing bodies, which were more beautiful than anything he had ever seen.

Adam knelt beside them and kissed his father’s neck and his mother’s lips. Siss opened her arms and enfolded her son, too.

And Adam asked, with his face against his mother’s cheek, which was wet and warm, “Is this what love is?”

And his mother answered, “Yes, honey,” and his father said, in a muffled kind of way, “It’s everything there is, son.”

Adam reached out for the berries and put one in his mother’s mouth and one in his father’s and one in his. Then he got up to give one to the baby.

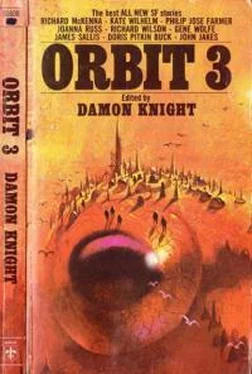

In Orbit 1, it was “The Secret Place”; in Orbit 2, “Fiddler’s Green.” Now here is “Bramble Bush,” and it is the last. After this, there will be no more stories by Richard McKenna in Orbit.

This remarkable story was written early in McKenna’s career: he brought it to the Milford Writers’ Conference in 1960 or thereabouts. I did not understand a word of it then, and concluded that it was a failure. After McKenna’s death in 1964, it turned up in a batch of manuscripts Eva McKenna sent me. Reading it again, with more care, I discovered that far from being muddled all the way through, it was a brilliant and perfectly lucid story, buried under a mass of trivial confusions inadvertently or deliberately introduced by the author. With Mrs. McKenna’s permission, therefore, I made a number of minor changes, mostly in the characters’ names. (In the original version, half a dozen of the characters had names that looked or sounded alike.) Except for these, the story remains as McKenna wrote it. It is that rare thing, a pure science fiction story. It deals with one of the most puzzling questions in relativity, one to which Einstein never gave an unequivocal answer: If all four spacetime dimensions are equivalent, how is it that we perceive one so differently from the rest?

Only a writer with McKenna’s peculiar talents and training could have given this solution, which involves the anatomy of the nervous system, symbology, anthropology, the psychology of perception ... and magic.

Bramble Bush

by Richard McKenna

Team Leader Ed Gard did not tell them until after Explorer Vessel M-24 rotated irreversibly into subspace.

“We’ll not come out by kappa-12 Carinae,” he said then to the five men standing clumped in the" control room. “We’re going to alpha-1 Centauri.”

Fat Webb Onderdonck, the climatologist, exploded. “A field trip for kids! How come?”

“Isn’t it already settled?” asked Minelli, the slender geologist.

Shipman Isaac McPherson punched a reference combination and glanced at the lighted screen.

“One Earth-type planet named Proteus,” he said, frowning. “Never been a landing. Now why didn’t I ever wonder about that before? My God, the nearest system to Earth—”

“Only in the Riemannian sense,” Onderdonck broke in. “Means nothing relative to subspace.” McPherson’s craggy face cleared.

“But we’ve taken them in order of Riemannian contiguity all along,” objected Chalmers, the biochemist. “This exception does seem unaccountable. There must be a reason.” His thin, sharp features were troubled.

“Overlooked in the shuffle. Maybe a misfiled report. What’s one planet anyway, among a billion?” Webb Onderdonck scowled.

“Not so, Webb,” Gard said, squaring massive shoulders. “In the past century the Corps projected several trips to Proteus. Each one aborted through a long series of personnel accidents and other delays. We are the first to get away.”

“Why the secrecy? Who’s being fooled?”

“Fate, maybe. A sop to superstition. Sit down, people, and I’ll explain.”

Seated along the wall bench, all but the scowling fat man, they listened as their tall leader paced and talked. Proteus had been his personal mystery since he was ten years old, he said, and the mystery was that no one else was curious.

“Everybody shushed my questions and got mad when I persisted,” he said. “Just one of those things, they kept telling me, too many planets to worry about any single one. It came to me that the most insoluble mystery is one that no one will admit exists.”

He aimed his education at the Explorer Corps, he went on, enlisted and in time qualified as team leader. When he tried to rouse official interest in a trip to Proteus he hit a stone wall of indifference grading into covert hostility. But finally he had infected Vane, the project coordinator at Denverport, with his own curiosity. Together they had planned this secret diversion of a routine Carina trip.

“So here we go, people. Don’t all hate me at once.” He put up his hands in mock-guard.

“Curiosity killed a cat,” Onderdonck snorted, jowls quivering. “Your mystery is childish nonsense. This will finish you in the Corps, and Vane too.”

“How did curiosity kill the cat?” Hank Chalmers asked. “I don’t like this either, Webb, but I can’t put my finger on a reason.”

“A planet’s a planet, all in the day’s work,” Minelli soothed. “Let’s do a job on this Proteus and there’ll be no more mystery.”

Joe Svirsky, the biologist, stood up. He was a stocky, graying man with cheekbones prominent in a broad face under slanting gray eyes.

“This is no ordinary mission, my brothers,” he said gravely. “We must be careful.”

“Amen to that,” Gard grinned. “Afterward let the Corps bounce me as far as it likes. I’ve been pointing for this all my life.”

Proteus circled the smaller star close in. Its day was fourteen standard hours, no axial tilt and so no seasons, gravity point seven, air breathable but hot and humid, the instruments told them. Gard called a pre-landing conference in the main workroom on their second day in orbit.

“Mean relief under ninety feet. Eighty-five percent sea, most of it epeiric. Never saw an Earth-type so leveled off,” Minelli said.

“Mean annual temperature estimate twenty degrees above optimum,” Onderdonck said, looking at Gard across the table. “That alone rules out settlement. No landing necessary now or ever and pop goes your mystery. Let’s go home.”

“We must sample the biota for a complete report,” Gard disagreed. “We serve man’s land hunger and his curiosity.”

“Speak for yourself!” Onderdonck snapped, rising and propping himself on pudgy fingers. “I invoke article ten of regulations and call for a vote of supersession.”

“Hold on, Webb, that makes bad feeling,” Pete Minelli said. “Besides, I want a closer look at that textbook peneplain down below.”

Onderdonck insisted. Only Chalmers, glancing apologetically at Gard, voted with him.

“Take her down, Ike, the place Minelli picked,” Gard told the shipman.

McPherson set her down on a continental dome, a comparatively well-drained area of grassy swales and broad-leaf tree clumps.

“Looks ordinary as hell,” McPherson said, standing at the foot of the ramp.

“Hot as hell too,” Minelli said. “Steam bath. Me for swimming trunks.” He started back aboard.

“Just a minute, Pete,” Gard called after him. “I was about to propose we stay on ship-time on account of the short local day. Okay with you?”

Читать дальше