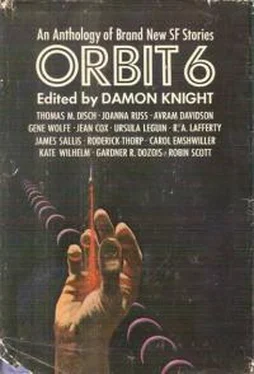

Дэймон Найт - Orbit 6

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Дэймон Найт - Orbit 6» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1970, Издательство: G. P. Putnam's Sons, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Orbit 6

- Автор:

- Издательство:G. P. Putnam's Sons

- Жанр:

- Год:1970

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Orbit 6: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Orbit 6»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Orbit 6 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Orbit 6», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

This, admittedly, lacked clarity. It had come to him thick and fast, and it was colored not a little by cheap red wine. To fix its outlines a bit more firmly in his own mind he tried to “get it down” in his letter to Art News:

Sirs:

I write to you concerning F.R. Robertson’s review of my book, though the few words I have to say bear but slightly upon Mr. Robertson’s oracles, as slightly perhaps as these bore upon Homo Arbitrans.

Only this — that, as Gödel has demonstrated in mathematics, Wittgenstein in philosophy, and Duchamp, Cage, and Ashbery in their respective fields, the final statement of any system is a self-denunciation, a demonstration of how its particular little tricks are done — not by magic (as magicians have always known) but by the readiness of the magician’s audience to be deceived, which readiness is the very glue of the social contract.

Every system, including my own and Mr. Robertson’s, is a system of more or less interesting lies, and if one begins to call these lies into question, then one ought really to begin with the first. That is to say, with the very questionable proposition on the title page: Homo Arbitrans by John Benedict Harris.

Now I ask you, Mr. Robertson, what could be more improbable than that? More tentative? More arbitrary?

He sent the letter off, unsigned.

V

He had been promised his photos by Monday, so Monday morning, before the frost had thawed on the plate-glass window, he was at the shop. The same immodest anxious interest to see his pictures of Eyüp possessed him as once he had felt to see an essay or a review in print. It was as though these items, the pictures, the printed words, had the power to rescind, for a little while, his banishment to the realm of judgment, as though they said to him: “Yes, look, here we are, right in your hand. We’re real, and so you must be too.”

The old man behind the counter, a German, looked up mournfully to gargle a mournful ach . “Ach, Mr. Harris! Your pictures are not aready yet. Come back soon at twelve o’clock.”

He walked through the melting streets that were, this side of the Golden Horn, jokebooks of eclecticism. No mail at the consulate, which was only to be expected. Half-past ten.

A pudding at a pudding shop. Two lire. A cigarette. A few more jokes: a bedraggled caryatid, an Egyptian tomb, a Greek temple that had been changed by some Circean wand into a butcher shop. Eleven.

He looked, in the bookshop, at the same shopworn selection of books that he had looked at so often before. Eleven-thirty. Surely, they would be ready by now.

“You are here, Mr. Harris. Very good.”

Smiling in anticipation, he opened the envelope, removed the slim warped stack of prints.

No.

“I’m afraid these aren’t mine.” He handed them back. He didn’t want to feel them in his hand.

“What?”

“Those are the wrong pictures. You’ve made a mistake.”

The old man put on a pair of dirty spectacles and shuffled through the prints. He squinted at the name on the envelope. “You are Mr. Harris.”

“Yes, that is the name on the envelope. The envelope’s all right, the pictures aren’t.”

“It is not a mistake.”

“These are somebody else’s snapshots. Some family picnic. You can see that.”

“I myself took out the roll of film from your camera. Do you remember, Mr. Harris?”

He laughed uneasily. He hated scenes. He considered just walking out of the shop, forgetting all about the pictures. “Yes, I do remember. But I’m afraid you must have gotten that roll of film confused with another. I didn’t take these pictures. I took pictures at the cemetery in Eyüp. Does that ring a bell?”

Perhaps, he thought, “ring a bell” was not an expression a German would understand.

As a waiter whose honesty has been called into question will go over the bill again with exaggerated attention, the old man frowned and examined each of the pictures in turn. With a triumphant clearing of his throat he laid one of the snapshots face up on the counter. “Who is that, Mr. Harris?”

It was the boy.

“Who! I… I don’t know his name.”

The old German laughed theatrically, lifting his eyes to a witnessing heaven. “It is you, Mr. Harris! It is you!”

He bent over the counter. His fingers still refused to touch the print. The boy was held up in the arms of a man whose head was bent forward as though he were examining the close-cropped scalp for lice. Details were fuzzy, the lens having been mistakenly set at infinity.

Was it his face? The mustache resembled his mustache, the crescents under the eyes, the hair falling forward…

But the angle of the head, the lack of focus — there was room for doubt.

“Twenty-four lire please, Mr. Harris.”

“Yes. Of course.” He took a fifty-lire note from his billfold. The old man dug into a lady’s plastic coin purse for change.

“Thank you, Mr. Harris.”

“Yes. I’m… sorry.”

The old man replaced the prints in the envelope, handed them across the counter.

He put the envelope in the pocket of his suit. “It was my mistake.”

“Good-bye.”

“Yes, good-bye.”

He stood on the street, in the sunlight, exposed. Any moment either of them might come up to him, lay a hand on his shoulder, tug at his pantleg. He could not examine the prints here. He returned to the sweetshop and spread them out in four rows on a marble-topped table.

Twenty photographs. A day’s outing, as commonplace as it had been impossible.

Of these twenty, three were so overexposed as to be meaningless and should not have been printed at all. Three others showed what appeared to be islands or different sections of a very irregular coastline. They were unimaginatively composed, with great expanses of bleached-out sky and glaring water. Squeezed between these, the land registered merely as long dark blotches flecked with tiny gray rectangles of buildings. There was also a view up a steep street of wooden houses and naked wintry gardens.

The remaining thirteen pictures showed various people, and groups of people, looking at the camera. A heavyset woman in black, with black teeth, squinting into the sun — standing next to a pine tree in one picture, sitting uncomfortably on a natural stone formation in the second. An old man, dark-skinned, bald, with a flaring mustache and several days’ stubble of beard. Then these two together — a very blurred print. Three little girls standing in front of a middle-aged woman, who regarded them with a pleased, proprietorial air. The same three girls grouped around the old man, who seemed to take no notice of them whatever. And a group of five men: the spread-legged shadow of the man taking this picture was roughly stenciled across the pebbled foreground.

And the woman. Alone. The wrinkled sallow flesh abraded to a smooth white mask by the harsh midday light.

Then the boy snuggling beside her on a blanket. Nearby small waves lapped at a narrow shingle.

Then these two still together with the old woman and the three little girls. The contiguity of the two women’s faces suggested a family resemblance.

The figure that could be identified as himself appeared in only three of the pictures: once holding the boy in his arms; once with his arm around the woman’s shoulders, while the boy stood before them scowling; once in a group of thirteen people, all of whom had appeared in one or another of the previous shots. Only the last of these three was in focus. He was one of the least noticeable figures in this group, but the mustached face smiling so rigidly into the camera was undeniably his own.

He had never seen these people, except, of course, for the woman and the boy. Though he had, hundreds of times, seen people just like them in the streets of Istanbul. Nor did he recognize the plots of grass, the stands of pine, the boulders, the shingle beach, though once again they were of such a generic type that he might well have passed such places a dozen times without taking any notice of them. Was the world of fact really as characterless as this? That it was the world of fact he never for a moment doubted.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Orbit 6»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Orbit 6» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Orbit 6» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.