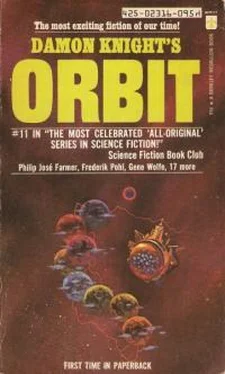

Дэймон Найт - Orbit 11

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Дэймон Найт - Orbit 11» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1973, ISBN: 1973, Издательство: Berkley Medallion, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Orbit 11

- Автор:

- Издательство:Berkley Medallion

- Жанр:

- Год:1973

- ISBN:0425023168

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Orbit 11: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Orbit 11»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Orbit 11 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Orbit 11», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Your sense of history is too strong,” Daw told her. He nearly added, “Like Wad’s,” but thought better of it and said instead, “For some reason that reminds me—you were going to tell me why you were talking to Wad, but you never did.”

“Wad is the boy that looks like you? I said I would if you’d tell me about him.”

“That’s right,” Daw said, “I didn’t finish.” They were leaving the tube now, thrown like the debris from an explosion through an emptiness whose miles-distant walls seemed at first merely roughened, but whose roughness resolved into closely-packed machines, a spininess of shafts and great gears and tilted beams—all motionless.

“You told me about the midshipmen,” Helen reminded him. “I think I can guess the rest, except that I don’t know how it’s done.”

“And what’s your guess?”

“You said that you were Wad—at least in a sense. In some way you’re training yourself.”

“Time travel? No.”

“What then?”

“Future captains are selected by psychological testing when, as cadets, they have completed their courses in basic science. Then instead of being sent to space as junior officers, they go as observers on a two-year simulated flight—all right on Earth. The advantage is that they see more action in the two years of simulation than they’d get in twenty of actual service. They go through every type of emergency that’s ever come up at least once, and some more than once—with variations.”

“That’s interesting; but it doesn’t explain Wad.”

“They have to get the material for the simulations somewhere. Sure, in most of it the midshipman just views, but you don’t want to train him to be a detached observer and nothing else. He has to be able to talk to the people on shipboard, and especially the captain, and get meaningful, typical replies. To get material for those conversations a computer on every navy ship simulates a midshipman whom the captain and crew must treat as an individual.”

“Do they all look like you?”

“They have to look like someone, so they’re made to look—and talk and act—as the captain himself did during his midshipman days. It’s important, as I said, that the captain treat his midshipman as a son, and that way there’s more—” Daw paused.

“Empathy?” He could hear the fragile smile.

“That’s your word. Sympathy.”

“Before it was corrupted by association with pity, that used to mean what empathy does now.”

A new voice rang in Daw’s headphones: “ Captain! Captain!”

“Yes. Here.”

“This is Polk, Captain. We didn’t want to bother you, sir, but we’ve got the numbers from the central registers in that corner module, and from the form—well, we think you’re right. It’s a bearing.”

“You’ve got duplicates of the charts, don’t you? Where were they going?”

“What star, you mean, sir?”

“Yes, of course.”

“It doesn’t seem to be a bearing for any star, Captain. Not on their charts, or ours either.”

Helen Youngmeadow interrupted to say: “But it has to point to some star! There are millions of them out there.”

Daw said, “There are billions—each so remote that for most purposes it can be treated as a nondimensional point.”

“The closest star to this bearing’s about a quarter degree off,” Polk told her. “And a quarter of a degree is, well ma’am,- a hell of a long way in astrogation.”

“Perhaps it isn’t a bearing then,” the girl said.

Daw asked, “What does it point to?”

“Well, sir—”

“When I asked you a minute ago what the bearing indicated, you asked if I meant what star. So it does point to something, or you think it does. What is it?”

“Sir, Wad said we should ask Gladiator what was on the line of the bearing at various times in the recent past. I guess he thought it might be a comet or something. It turned out that it’s pointing right to where our ship was while we were making our approach to this one, sir.”

Unexpectedly, Daw laughed. (Helen Youngmeadow tried to remember if she had ever heard him laugh before, and decided she had not.)

“Anything else to report, Polk?”

“No, sir.”

She asked, “Why did you laugh, Captain?”

“We’re still on general band,” Daw said. “What do you say we switch over to private?”

His own dials bobbed and jittered as the girl adjusted her controls.

“I laughed because I was thinking of the old chimpanzee experiment; you’ve probably read about it. One of the first scientists to study the psychology of the nonhuman primates locked a chimp in a room full of ladders and boxes and so on—”

“And then peeked through the keyhole to see what he did, and saw the chimpanzee’s eye looking back at him.” Now Helen laughed too. “I see what you mean. You worked so hard to see what they had been looking at—and they were looking at us.”

“Yes,” said Daw.

“But that doesn’t tell you where they went, does it?”

Daw said, “Yes, it does.”

“I don’t understand.”

“They were still here when we sighted them, because we changed course to approach this ship.”

“Then they abandoned the ship because we came, but that still doesn’t tell you where they went.”

“It tells me where they are now. If they didn’t leave before we had them in detection range, they didn’t leave at all—we would have seen them. If they didn’t leave at all, they are still on board.”

“They can’t be.”

“They can be and they are. Think of how thinly we’re scattered on Gladiator. Would anyone be able to find us if we didn’t want to be found?”

Far ahead in the dimness her utility light answered him. He saw it wink on and dart from shadow to shadow, then back at him, then to the shadows again. “We’re in no more danger than we were before,” he said.

“They have my husband. Why are they hiding, and who are they?”

“I don’t know; I don’t even know that they are hiding. There may be very few of them—they may find it hard to make us notice them. I don’t know.”

The girl was slowing, cutting her jets. He cut his own, letting himself drift up to her. When he was beside her she said: “Don’t you know anything about them? Anything?”

“When we first sighted this ship I ran an electronic and structural correlation on its form. Wad ran a bionic one. You wouldn’t have heard us talking about them because we were on a private circuit.”

“No.” The girl’s voice was barely audible. “No, I didn’t.”

“Wad got nothing on his bionic correlation. I got two things out of mine. As a structure this ship resembles certain kinds of crystals. Or you could say that it looks like the core stack in an old-fashioned computer—cores in rectangular arrays with three wires running through the center of each. Later, because of what Wad had said, I started thinking of Gladiator; so while we were more or less cooling our heels and hoping your husband would come in, I did what Wad had and ran a bionic correlation on her.” He fell silent.

“Yes?”

“There were vertebrates—creatures with spinal columns—before there were any with brains; did you know that? The first brains were little thickenings at the end of the spinal nerves nearest the sense organs. That’s what Gladiator resembles—that first thin layer of extra neurons that was the primitive cortex. This ship is different.”

“Yes,” the girl said again.

“More like an artificial intelligence—the computer core stack of course, but the crystals too; the early computers, the ones just beyond the first vacuum-tube stage, used crystalline materials for transducers: germanium and that kind of thing. It was before Ovshinsky came up with ovonic switches of amorphous materials.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Orbit 11»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Orbit 11» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Orbit 11» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.