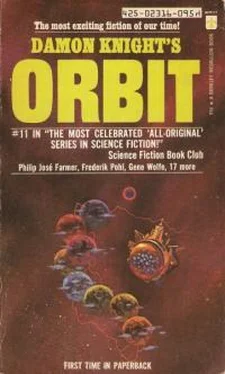

Дэймон Найт - Orbit 11

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Дэймон Найт - Orbit 11» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1973, ISBN: 1973, Издательство: Berkley Medallion, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Orbit 11

- Автор:

- Издательство:Berkley Medallion

- Жанр:

- Год:1973

- ISBN:0425023168

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Orbit 11: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Orbit 11»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Orbit 11 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Orbit 11», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It hurts. It takes a long time, and I can’t even see their shadows. It hurts.

They finish, they untie me, they thrust me out. I hear them laughing as I stumble onto the moving floor. It is an ugly sound. My head aches. I go back to my place and sit down. The lights are too bright, the blacks too dark, but I’m not allowed to stop. My hands are trembling. I remember that I’ve thought of a new way to make myself see, and for a while I can forget the pain.

Finally my time is up. The floor takes us back to our sleeping places. I crawl inside, crouching. I must fit my ankle against the cannulae or the panel at my feet will not slide shut, and I will be punished. I remember soft fragrant pallets of pine boughs and the pleasant soft scratchiness of those needles. Tonight I do not fear the pain. I do what is expected of me and wait for the panel to cut off the light.

I reach up and touch my eyes. Anticipation tickles my throat. It will be so good to see the colors again and remember what they really are. I know this way will work. I reach up—

My hands jerk away. They cannot punish me here. They cannot. This is my place, my time. ... I reach again, and the shock is stronger. My fingers jerk back reflexively and the back of my head hurts from the pressure of the bed. My hands creep up once more. The shock is so strong that the spark flashes back to my brain. I smell seared flesh, and my fingers are numb. I put them to my lips. I can taste blood. I know they will hurt tomorrow, when I must use them at my work.

But even if they did not hurt, I could not touch my eyes. The shadow-people will not let me. If only they would, I know that I could see.

I want to cry. I wish that I had tears.

Frederik Pohl

I REMEMBER A WINTER

I remember a winter when the cold snapped and stung, and it would not snow. It was a very long time ago, and in the afternoons Paulie O’Shaughnessy would come by for me after school and we’d tell each other what we were going to do with our lives. I remember standing with Paulie on the corner, with my breath white and my teeth aching from the cold air, talking. It was too cold to go to the park and we didn’t have any money to go anywhere else. We thumbed through the magazines in the secondhand bookstore until the lady threw us out. “Let’s hitch downtown,” said Paulie; but I could feel how cold the wind would be on the back of the trolley cars and I wouldn’t. “Let’s sneak in the Carlton,” I said, but Paulie had been caught sneaking in to see the Marx Brothers the week before and the usher knew his face. We ducked into the indoor miniature golf course for a while; it had been an automobile showroom the year before and still smelled of gas. But we were the only people there, and conspicuous, and when the man who rented out the clubs started toward us we left.

So we Boy Scout-trotted down Flatbush Avenue to the big old library, walk fifty, trot fifty, the cold air slicing into the insides of our faces, past the apple sellers and the winebrick stores, gasping and grunting at each other, and do you know what? Paulie picked a book off those dusty old shelves. We didn’t have cards, but he liked it too much to leave it unfinished. He walked out with it under his coat; and fifteen years later, shriveled and shrunken and terrified of the priest coming toward his bed, he died of what he read that day. It’s true. I saw it happen. And the damn book was only Beau Geste.

I remember the summer that followed. I still didn’t have any money but I found girls. That was the summer when Franklin Roosevelt flew to Chicago in an airplane to accept his party’s nomination to the Presidency, and it was hotter than you would believe. Standing on the corner, the sparks from the trolley wheels were almost invisible in the bright sun. We hitched to the beach when we could, and Paulie’s pale, Jewish-looking face got red and then freckled. He hated that; he wanted to be burned black in the desert sun, or maybe clear-skinned and cleft-chinned with the mark of a helmet strap on his jaw.

But I didn’t see much of Paulie that summer. He had finished all the Wren books by then and was moving on to Daredevil Aces ; he’d wheedled a World War French bayonet out of his uncle and had taken a job delivering suits for a tailor shop, saving his money to buy a .22. I saw much more of his sister. She was fifteen then, which was a year older than Paulie and I were. In his British soldier-of-fortune-role-playing he cast her as much younger. “Sport,” he said to me, eyes a little narrowed, half-smile on his lips, “do what you like. But not with Kitty.”

As a matter of fact, in the end I did do pretty much as I liked with Kitty, but we had each married somebody else before that and it was a long way from 1932. But even in 1932 I tried. On a July evening I finally got her to go up on the roof with me; it was no good; somebody else was there ahead of us, and Kitty wouldn’t stay with them there. “Let’s sit on the stoop,” she said. But that was right out in the street, with all the kids playing king-of-the-hill on a pile of sand.

So I took her by the elbow, and I walked her down the avenue, talking about Life and Courage and War. She had heard the whole thing before, of course, as much as she would listen to, but from Paulie, not from me. She listened. It was ritual courtship, as formal as a dog lifting his leg. It did not seem to me that it mattered what I said, as long as what I said was masculine.

You can’t know how masculine I wanted to be for Kitty. She was without question the prettiest doll around. She looked like—well, like Ginger Rogers, if you remember, with a clean, friendly face and the neatest, slimmest hips. She knew that. She was studying dancing. She was also studying men, and God knows what she thought she was learning from me.

When we got to Dean Street I changed from authority on war to authority on science and told her that the heat was only at ground level. Just a little way above our heads, I told her, the air was always cool and fresh. “Let’s go up on the fire escape,” I said, nudging her toward the Atlantic Theatre.

The Atlantic was locked up tight that year; Paulie and I were not the only kids who didn’t have movie money. But the fire escapes were open, three flights of strap-iron stairs going up to what we called nigger heaven. I don’t know why, exactly. The colored kids from the neighborhood didn’t sit up there; in fact, I never saw them in the movies at all. The fire escapes made a good place to go. Paulie and I went up there a lot, when he wasn’t working, to look down on everybody in the street and not have anyone know we were watching them. So Kitty and I went up to the second landing and sat on the steps, and in a minute I put my arm around her.

And all of this, you know, I’d thought out like two or three months in advance, going up there by myself and experimentally bouncing my tail up and down on the steps for discomfort, calculating in a wet morning in May what it would be like right after dark in August, and all. It was a triumph of fourteen-year-old forethought. Or it would have been if it had come to anything. But somebody coughed, higher up on the fire escape.

Kitty jabbed me with her elbow, and we listened. Somebody was mumbling softly up above us. I don’t know if he had heard us coming. I don’t think so. I stood up and peered around the landing, and I saw candlelight, and an old man’s face, terribly lined and unshaven and sad. He was living there. All around the top landing he had carefully put up sheets of cardboard from grocery cartons, I suppose to keep the rain out. If it rained. Or perhaps just to keep him out of public view. He was sitting on a blanket, leaning his forearm on one knee, looking at the candle, talking to himself.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Orbit 11»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Orbit 11» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Orbit 11» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.