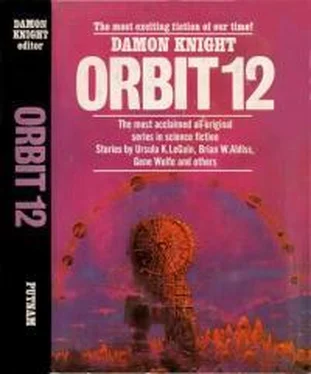

Дэймон Найт - Orbit 12

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Дэймон Найт - Orbit 12» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Orbit 12

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Orbit 12: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Orbit 12»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Orbit 12 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Orbit 12», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

As he was making this dismal speech, he was leading me through a side door and across a narrow court. His steps were heavy, his manner slow and deliberate. I wondered at him and his situation. I had no doubt that he was among the greatest painters in the land, and not just in Malaria; yet he had wasted a decade here—indeed, seemed to have settled here, forever dawdling on the Mantegan frescoes, forever experimenting with a dozen other arts. Sometimes he quarrelled with Volpato and threatened to leave. All the while, he complained of Volpato’s stinginess. Yet Volpato also seemed to have some justice on his side when he, in his turn, complained that he housed and supported an idle painter and got no reward for it

We entered the banqueting hall, with its pendant vaulting and splendid lattice window, fantastic with carved transoms, overlooking the River Toi. Dalembert’s unfinished frescoes took their orientation from this window, and their lighting schemes. The theme was the Activities of Man and the Prescience of God. Only one or two pastoral scenes and the dinosaur hunt were complete; for the rest, one or two isolated figures or details of background stood out in a melancholy way behind the scaffolding.

As Dalembert plodded to and fro, expounding what he intended to do, I could see something of his vision, could see the entire hall as a sweet elegiac rhapsody of Youth, as he planned it to be. The cartoons scattered about showed that his wonderful phantasies, his glorious and ample figures, drawn together in grandiose colour orchestrations, opened new horizons of painting. In the marriage scene, sketched in and part painted, the wedding of an early Mantegan to Beatrice of Burgundy was commemorated. What delicacy and perception!

“The secret is the light,” I said.

For light seemed to linger on the princess with a serene if sad intimacy, and on her banners and followers with no less lucidity. The church with its galleries and the view beyond were carefully drawn in, proof of Dalembert’s marvellous command of perspective.

The artist paused before a military scene, where soldiers were shooting birds and a peasant boy stood comically wearing a large helmet and holding a shield. In the background rose a small fantastic city, drawn and washed over.

Dalembert dismissed it all with a curt wave of one hand.

“That’s all I’ve done here since we last met. The whole task is impossible without adequate funds. Adequate talent, too.”

“It’s beautiful, Nicholas. The city, with its ragged battlements, its towers, domes, and overhanging garde-robes—how well it’s set amid its surroundings!”

“Well enough, perhaps, yet there’s nothing there which my master, Albrecht, could not have done thirty years ago—fifty years ago.”

“Surely perfection is more important than progression?”

He looked at me with his dark and burning eyes. “I didn’t take you for a man who preferred a stagnant pond to running water. Ah, I can do nothing, nothing! Outside beyond these crumbling walls is that great burning world of triumphs and mobilities, while I’m here immobile. Only by art, only through painting, can one master it and its secrets! Seeing is not enough—we do not see until we have copied it, until we have faithfully transcribed everything . . . everything . . . especially the divine light of heaven, without which there is nothing.”

“You would have here, if you could only continue with your work, something more than a transcription—”

“Don’t flatter me. I hate it sincerely. I’ll take money, God knows I’ll take money, but not praise. Only God is worthy of praise. There is no merit anywhere but He gives it. See the locks of that soldier’s hair, the bloom on the boy’s cheek, the bricks of the walls of the fortification, the plumage of the little bird as it flutters to the sward—do I have them exact? No, I do not! I have imitations! You don’t imagine—you are not deceived into believing there is no wall there, are you?”

“But I expect the wall. Your accomplishment is that through perspective and colouring, you show us more than a wall.”

“No, no, far less than a wall ... A wall is a wall, and all my ambition can only make it less than a wall. You look for mobility and light—I give you dust and statuary! Its blasphemy—life offered death!”

I did not understand him, but I said nothing. He stood stock still, fixing his gaze in loathing on the fortified city he had depicted, and I was aware of the formidable solidity of him, as if he were constructed of condensed darkness inside his tattered cloak.

Finally he turned away and said, as if opening a new topic of conversation, “Only God is worthy of praise. He gives and takes all things.”

“He has also given us the power to create.”

“He gives all things, and so many we are unable to accept. We stand in a new age, Master Prian. This is a new age—I can feel it all about me, cooped up though I am in this dreadful place. Now at last—for the first time in a thousand years, men open their eyes and look about them. For the first time, they construct engines to supplement their muscles and consult libraries to supplement their meagre brains. And what do they find? Why, the vast, the God-given continuity of the world! For the first time, we may see into the past and into the future. We find we are surrounded by the classical ruins of yesterday and the embryos of the future! And how can these signs from the Almighty be interpreted save by painting? Painting gives and therefore demands universal knowledge . . .”

“And, surely, also the instincts are involved—”

“Whereas I know nothing—nothing! For years and years—all my life I’ve slaved to learn, to copy, to transcribe, and yet I have not the ability to do what a single beam of light can do—here, my friend, come with me, and I’ll show you how favourably one moment of God’s work compares with a year of mine!”

He seized my tunic and drew me from the hall, leaving the door to swing behind us. Again we retraced the court, which echoed to his grudging step. We returned to the stable that housed him. The little children sprawled and played. Dalembert brushed them aside. He climbed the ladder to his loft, pushing me before him. The children cried words of enticement to him to join their play; he shouted back to them to be silent.

The loft was his workshop. One end was boarded off. The rest was filled with his tables and materials, with his endless pots and brushes of all sizes, with piles of unruly paper, with instruments of every description, with geometrical models, and with a litter of objects which bespoke his intellectual occupations: an elk’s foot, a buffalo horn, skulls of aurochs and hypsilophodon, piles of bones, a plaited hat of bark, a coconut, fir cones, shells, branches of coral, dead insects, and lumps of rock, as well as books on fortifications and other subjects.

He brushed through these inanimate children too. Flinging back a curtain at the rear of the workshop, he gestured me in, crying, “Here you can be in God’s trouser pocket and survey the universe! See what light can paint at the hand of the one true Master!”

The curtain fell back into place. We were in a small, stuffy and enclosed dark room. A round table stood in the centre of it. On the table was a startling picture painted in vivid colours. I took one glance at it and knew that Dalembert had happened on some miraculous technique, combining all arts and all knowledge, which set him as far apart from all other artists as men are apart from the other animals with which they share the globe. Then something moved in the picture. A second glance told me this was nothing but a camera obscura! Looking up, I saw a little aperture through which the light entered. Directed by a lens, it shone in through a small tower set in the roof of the stable.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Orbit 12»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Orbit 12» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Orbit 12» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.