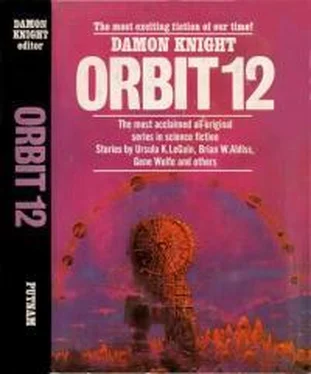

Дэймон Найт - Orbit 12

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Дэймон Найт - Orbit 12» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Orbit 12

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Orbit 12: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Orbit 12»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Orbit 12 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Orbit 12», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“How can your husband afford to pay him?”

She laughed. “He can’t! That’s why Dalembert still lives here. He is so lazy! At least he has a free roof over his head. And he’s safer here in isolation now there’s plague again in Malacia.”

“It always comes with the hot weather.”

“Go and talk to him. You know the way. Well meet this evening in the chapel.”

It was always pleasant to stroll through the irregularities of the Mantegan family castle. Its perspectives were like none I knew in the world, with its impromptu landings, its unexpected chambers, its dead ends, its never-ending stairs, its descents from stone into wood, its fine marbles and rotting plasters, its noble statues and ignoble decay.

The Mantegan family had never been rich within memory of living man; now they were positively bankrupt, and my brother-in-law, Volpato, was the last of the line. It was whispered of him that he had poisoned both his elder brother, Claudio, and his elder sister, Saprista, in order to gain control of what little family wealth remained—Claudio by spreading a biting acid on the saddle of his stallion, so that the deadly ichor moved from the anus upward to the heart, Saprista by smearing a toxic orpiment on a golden statue of the Virgin which she was wont to kiss during her private devotions, so that she died rotting from the lips inward. If all this was true or not, Volpato did not reveal. Evil stories clustered about him, but he acted kindly enough in his treatment of my sister, as well as having the goodness to be away for long periods, seeking his fortune among the megatherium-haunted savannahs of the New World.

Meanwhile, his castle on the banks of the Toi fell into decay, and his wife did not become a mother. But I was proud of it, and of my dear sister for marrying so well—the only one of us to marry into court circles.

The way to Dalembert’s quarters lay through a long gallery in which Volpato displayed some of his treasures. Rats scuttled among them in the dim light. Among much that was rubbish were some fine blue-glazed dishes brought back from the lands of the Orinoco; ivories of mastodon carved during the last Neanderthal civilization for the royal house of Itssobeshiquetzilaha; parchments rescued by a Mantegan ancestor from the great library at Alexandria (among them two inscribed by the library’s founder, Ptolemy Soter) and portraits on silk of the seven Alexandrian Pleiades preserved from the same; a case full of Carthaginian ornament; jewels from the faery smiths of Atlantis; an orb reputed to have belonged to Birsha, King of Gomorrah, with the crown of King Bera of Sodom; a figurine of a priest with a lantern from the court of Caerleon-on-Usk; the stirrups of the favourite stallion of the Persian Bahram, Governor of Media, that great hunter; tapestries from Zeta, RaSka, and the courts of the early Nemanijas, together with robes cut for Miluitin; a lyre, chalice, and other objects from the Mousterian Period; a pretty oaken screen carved with dim figures of children and animals which I particularly liked, said to have come from distant Lyonesse before it sank below the waves; together with other items of some interest. But all that was of real worth had been sold off long ago, and the custodian sacked, to keep the family in meat and wine.

Tempted by a whim for which I could not account, I paused on my way among the mouldy relics and flung open an iron-strapped chest at random. Books bound in vellum met my gaze, among them one more richly jacketed, in an embroidered case studded with beads of ruby and topaz.

Taking it over to the light, I opened it and found it had no title. It was a collection of poems in manuscript, probably compiled by their creator. At first glance, the poems looked impossibly dull, odes to Liberty and the Chase, apostrophes to the Pox and Prosody, and so on. Then, as I flicked the pages, a shorter poem in terza rima caught my eye.

The poem consisted of four verses—the first two of which were identical with those adorning my bedroom window! Its title had reference to the emblematic animal over the main archway of the castle: “The Stone Watchdog at the Gate Speaks.” Whoever had transcribed part of the poem onto the window had been ingenious in accrediting its lines to the transparent glass. Amused by the coincidence, for coincidences were my daily dish, I read the final verses.

No less, while things celestial proceed

Unfettered, men and women all are slaves,

Chaining themselves to what their hearts

most need.

Methinks that whatsoe’er the mind once craves,

Will free it first and then it captive take

By slow degrees, down into Free Will’s graves.

Alas, Prosody had not replied when addressed! Yet the sentiment expressed might be true. I generally agreed with myself on the truth of the moralising in poems. Perhaps very little could be said that was a flat lie, provided it rhymed. Thoughtfully, I tore the page from its volume and tucked it in my doublet, tossing the book back into the chest, among the other antiquities.

Beyond the long gallery was the circular guard room, with its spiral stair up to the ramparts. Although the guard room had once been a building standing alone, it had long since come within the strangling embrace of the castle which, like some organic thing, had thrown out galleries and wings and additional courts, century by century, engulfing houses and other structures as it went. The old guard room retained something of its outdoor character despite being embedded inside the masonry of the castle; a pair of cavorts skimmed desperately round the shell, trapped after venturing in through carelessly boarded arrow slits on the inside-facing wall. On the floor lay a shred of Poseidon’s fur which the birds had dropped in their panic.

The character of the building changed again beyond the guard room. Here were stables, now converted to the usages of the Mantegan family’s resident artist, Nicholas Dalembert. Dalembert worked up in the loft, while his many children romped over the cobbles below.

I called to him. After a moment, his head appeared in the opening above, he waved, and began to climb down the ladder. He started to speak before he reached the bottom.

“So, Master Prian, it’s almost a year—it’s a long while since we’ve seen you at Mantegan. As God is my witness, this is an inhospitable place. I wonder what can have brought you here now. Not pleasure, I’ll be bound.”

I explained that I had been ill, that my sister was caring for me, and that I might be leaving on the morrow. “At first I thought it was the plague troubling me! There’s much of it in Malacia, especially in the Stary Most district—brought from the East, the medicos say, on the backs of the Turkish armies. Whenever you fall into a fever these days, you fear the worst.”

“You’re safe from the plague here, that at least I’ll say. The plague likes juice and succulence, and there’s nothing of that in this place.” He cast a gloomy eye down on his children, then busy flogging an old greyhound they had cornered; certainly they were not the plumpest of children.

Dalembert was a hefty fellow, as befits an artist who spends much time dissecting men, horses, and dinosaurs. The years had bowed his broad shoulders and trained a mass of grey hair about his shoulders. He had a huge cadaverous face with startling black eyes whose power was reinforced by the great black line of his eyebrows.

“I came to see how the frescoes were progressing, Nicholas.”

“They’re as incomplete as they were last Giovedi Grassi Festival, when you and the players were performing here. Nothing can be done—I can’t work anymore without pay and, although I don’t want to complain to you about your own brother-in-law, Milord Volpato would be better employed setting his lands in order than involving me in his schemes for self-aggrandisement. I’m so hard up I’ve even had to sack the lad who was colouring in my skies for me.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Orbit 12»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Orbit 12» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Orbit 12» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.