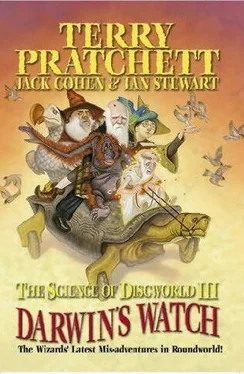

Terry Pratchett - Darwin's Watch

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Terry Pratchett - Darwin's Watch» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Darwin's Watch

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Darwin's Watch: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Darwin's Watch»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Darwin's Watch — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Darwin's Watch», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The recent amazing 'dinobird' discoveries in China - transitional creatures part way between dinosaurs and birds - have totally changed scientists' view of bird evolution. At some stage some dinosaurs started to develop feathers, though they couldn't then fly. The feathers had some other function, probably keeping the animal warm. Later, they turned out to be useful in wings. Some dinobirds effectively had four wings - two at the front, two at the back. It took a while before the standard `bird' body-plan settled down.

As for the dodo - we all know what it looked like, right? Fat little thing with a big hooked beak ... Such a famously extinct creature must be well documented in the scientific literature.

No, it's not. What we have is about ten paintings and half a stuffed specimen.[1]' We have more specimens of the archaeopteryx than we

[1] Rajith Dissanayake, 'What did the Dodo look like?' Biologist 51 (2004), 165-8.

do of the dodo. Why? The dodo went extinct, remember? And it did so before science really got interested in it. So few people recorded it, or studied it. It was there, not requiring special attention, and then it wasn't, and it was too late to start studying it. It isn't even certain what colour it was - many books say `grey', but it was more likely brown.

Yet, we all know exactly what it looked like. How come? Because we all saw it illustrated by Sir John Tenniel in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.

Say no more.

The great strength of Discworld narrative is that it makes fun of just those places where `education' has left us feeling a bit vulnerable: where we change the subject in the pub, or when our five-year-old asks us those probing questions. A running joke throughout the Science of Discworld series is what grammarians call 'privatives'. These are concepts that our minds seem quite happy with, even though a moment's thought shows that they're complete nonsense. Chapter 22 of The Science of Discworld discussed this notion, and we recap briefly.

It is entirely normal to speak of `cold coming in the window' or `ignorance spreading among the masses'. The opposites of these concepts, heat and knowledge, are real, but we've dignified their absence with words that do not correspond to actual things. In Discworld, we find 'knurd', which is super-sober, as far from ordinary sober as drunk is in the alcoholic direction. There are jokes about the speed of dark, which must be faster than the speed of light because dark has to get out of the way. On Discworld, Death exists as a (perhaps the) major character, but on Roundworld that word refers only to the absence of life.

People habitually label the absence of something with a word, instead of (or as well as) its presence: such words are the aforementioned privatives.

Sometimes this habit leads to mistakes. The classic case was the label `phlogiston', the substance that appears to be emitted by burning materials. You can see it coming out as smoke, flame, foam ... It took many years to demonstrate that burning was an intake of oxygen, not the emission of phlogiston. During the intervening period, many people had demonstrated that when metals burned they got heavier, and had therefore argued that phlogiston had negative weight. These were clever people; they weren't being stupid. The phlogiston idea really did work - until oxygen supplanted its explanations, and alchemists suddenly found that the paths into rational chemistry were easier.

Privatives are often very tempting. In What is Life?, a short book published in 1944, the great physicist Erwin Schrodinger asked precisely that question. At that time the Second Law of Thermodynamics - everything runs down, disorder always increases - was thought to be a fundamental principle about the universe. It implied that eventually everything would become a grey, cool soup of maximum entropy, maximum disorder: a `heat death' in which nothing interesting could happen. So in order to explain how, in such a universe, life could occur, Schrodinger claimed that life could only put off its individual tiny heat death by imbibing negative entropy, or 'negentropy'. Many physicists still believe this: that life is unnatural, selfishly causing entropy to increase more in its vicinity than it would otherwise do, by eating negentropy.

This tendency to deny what is happening before our very eyes is part of what it is to be human. Discworld exploits it for humorous and serious purposes. By building Discworld flat, Terry pokes fun at flat-Earthers; rather, he recruits his readers into a `we all know the Earth is round, don't we?' fellowship. The Omnians' belief in a round Disc, in Small Gods, adds a further twist.

We want to put what rational people are coming to believe into a general human context, so let's look at what everyone believes. In these days of fundamentalist terrorists we would do well to understand why a few people hold beliefs that are so different from the rational. These unexamined beliefs may be vitally important, because the ignorant people who espouse them think that they provide a good reason for killing us and our loved ones, even though they have never considered alternatives. People Who Know The Truth, by heredity or personal revelation or authority, are not concerned with logic or the validity of premises.

Nearly everybody who has ever lived has been one of those.

There have been a few sparse times and places - and we are hoping that the twenty-first century will host a few of them - in which onlookers are more ready to believe a disputant who is unsure, than one who is certain. But in today's politics, changing your mind in response to new evidence is seen as a weakness. When he was ViceChancellor at Warwick University, the biologist Sir Brian Follett remarked: `I don't like scientists on my committees. You don't know where they'll stand on any issue. Give them some more data, and they change their minds!' He understood the joke: most politicians wouldn't even realise it was a joke.

In order to discuss the kinds of explanation and understanding that are going to have future values, we need at least a simple geography of where human beings pin their faiths now. What kinds of world picture are most common? They include those of the authoritarian theist, the more-or-less imaginative theist, the more critical deist, and various kinds of atheists - from Buddhists and the followers of Spinoza to those, including many scientists and historians, who simply believe that the age of religion is behind us.

Most human beings of the last few millennia seem to have been authoritarian theists, and we still have many of them in our world; perhaps they are still a majority. Does this mean that we must give intellectual 'equal time' to these views (plural, because they're all very different: Zeus, Odin, Jahweh ... ), or can we just dismiss them all with `I have no need of that hypothesis', as Laplace supposedly said to Napoleon. Voltaire, aware that God making man in His image meant that God's nature might be deduced from man's, thought it at least possible that God has mischievously misinformed us about reward and punishment. Perhaps sinners are rewarded by Heaven and saints are given a taste of Hell. Our view is that all the various authoritarian theists are the contemporary bearers of an extremely successful memeplex, a package of beliefs designed and selected through the generations to ensure its own propagation.

A typical memeplex is the Jewish shema: `And these words ... you shall teach them to your children, muse on them when you get up and when you lie down ... Write them upon the doorposts of your house and upon your gates.' Like e-mail chain letters that threaten you with punishment if you fail to send them on to many friends, and with `luck' if you do send them on, the world's great religions have all promised pleasures for committed believers and transmitters, but pain for those who fail to adhere to the faith. Heretics, and those who leave the faith, are often killed by the faithful.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Darwin's Watch»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Darwin's Watch» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Darwin's Watch» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.