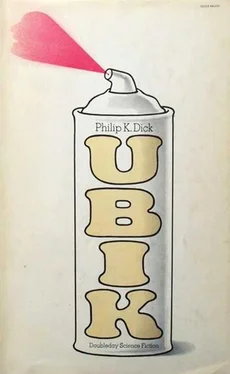

Philip Dick - Ubik

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Philip Dick - Ubik» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Ubik

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ubik: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Ubik»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Philip K. Dick’s searing metaphysical comedy of death and salvation (the latter available in a convenient aerosol spray) is tour de force of paranoiac menace and unfettered slapstick, in which the departed give business advice, shop for their next incarnation, and run the continual risk of dying yet again.

Ubik — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Ubik», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Furthermore, the epigraphs, by their non-pertinence to the narrative (where Ubik is a “reality-support” which comes in a spray-can and is not mentioned until chapter 10), may also be seen as a further subversion of the metaphysical concept of representation. An epigraph, like a title, is expected to serve as a comment and/or digest of the contents of a chapter, as if meaning were contained in the writing and could be summed up in the way that labels tell us what is inside a can at the supermarket. Impertinent or facetious epigraphs (or chapter headings, as in Maze of Death ) are a deliberate mislabeling which violates the commercial contract at the basis of the traditional novel.

The ironically inappropriate epigraphs to each chapter are thus a prelude to a more complex refutation of teleology and metaphysics in Ubik which depends upon recognizing the metaphysical presuppositions of the novel form itself. The classical bourgeois novel has been described in recent French literary theory as itself a metaphysical construct: traditionally, the novel has been a representative medium, and the concept of representation implies that the text is a restatement of some pre-existent meaning. 3 This attitude reduces reading to a looking through the text to the “real” meaning, whether that meaning be empirical reality, the author’s conscious design or his unconscious intentions. Such a transcendental bias valorizes the meaning (the signified ) while reducing the signifier to a means; it thereby masks and mystifies the text itself, both in its materiality (its texture) and in its production (the act of writing), in much the same way that—as Marx has shown—exchange value effects a masking and mystification of an object’s use-value as well as of the concrete human labor invested in it. 4

The traditional “representational novel” functions in this way as an ideological support for capitalism: it reinforces a transcendental conception of reality which mystifies the actual reality of the capitalist mode of production and the resultant repression and alienation. And although SF stories depict an imaginary reality, they have traditionally been concerned with the representation of a “fictional alternative to the author’s empirical environment” which is usually consistent and regulated by knowable laws. 5 As in other novels, there is a discernible, comprehensible meaning which informs the SF novel. (And this quite apart from any criticism one could make of the “contents” of the traditional SF novel.) But the reader of Ubik is refused any such final, definitive interpretation. At the end of the novel the reader seems to have at last achieved a complete explanation of the events according to which Joe Chip and the others are in half-life while Runciter is alive trying to contact them. The reader’s usual satisfaction in finishing a novel and looking back over how everything fits together derives from the formal confirmation of his conception of reality and, in the case of Ubik, from his relief at having finally resolved the disquieting tension between fictional reality and illusion. But this satisfaction is short-lived, for as Runciter leaves the Moratorium he discovers that the coins and bills in his pocket all bear the likeness of Joe Chip (as, at the beginning of the second part of the novel, Joe Chip and the other inertials’ money bore the likeness of Runciter)—an indication that this reality is also an illusion. And the novel concludes, as Runciter looks disbelievingly at his money: “This was just the beginning”: the beginning of an endless series of illusory realities, but for the careful reader, also the beginning of an end to a number of illusions about both reality and the novel. There is no satisfactory single interpretation of Ubik, my own included; and the reader’s traditional response—the discovery of that interpretation—is frustrated. However, that frustration was planned; this kind of text is no longer a window opening onto a transcendental meaning, but a mirror which reflects the reader’s look, forcing him out of his familiar reading habits while drawing his attention to the functioning of the novel as a form of manipulation.

UBIK IS NOT ONLY A DECONSTRUCTION of the metaphysical ideologies and the metaphysical formal implications of the classical bourgeois novel , but also of what (in Solaris ) Lem has described as the anthropomorphic presuppositions of science and of SF. Science is expressly demystified, first of all, through the disregard for scientific plausibility and through the single “scientific” description of a technological device in the novel:

A spray can of Ubik is a portable negative ionizer, with a self-contained, high-voltage, low-amp unit powered by a peak-gain helium battery of 25kv. The negative ions are given a counterclockwise spin by a radically biased acceleration chamber, which creates a centripetal tendency to them so that they cohere rather than dissipate. A negative ion field diminishes the velocity of anti-protophasons normally present in the atmosphere; as soon as their velocity falls they cease to be anti-protophasons and, under the principle of parity, no longer can unite with protophasons radiated from persons frozen in cold-pac; that is, those in half-life. The end result is that the proportion of protophasons not canceled by anti-protophasons increases, which means—for a specific time, anyhow—an increment in the net put-forth field of protophasonic activity… which the affected half-lifer experiences as greater vitality plus a lowering of the experience of low cold-pac temperatures. (§16)

This passage parodies scientific jargon which is often used to conceal ignorance rather then to convey information or knowledge (try reading a textbook description of cancer, for instance, a “disease” which science can “describe” without understanding it).

More importantly, Ubik is a critique of the a priori modes of perception which inform scientific thinking and which science often claims as objective empirical principles. 6 Dick undertakes this critique of scientific imperialism and tunnel-vision by carrying subjectivity to an extreme, by reminding us—as he has done perhaps most effectively in The Clans of the Alphane Moon and in Maze of Death —that the position of the observer is an extremely subjective perspective from which to deduce universal laws; that “reality” is a mental construct which may be undermined at any time.

Dick’s writing has often been labeled schizophrenic, but it is time to recognize that this is not necessarily a criticism, that schizophrenia may be, in R.D. Laing’s words from The Politics of Experience , a “breakthrough” rather than a “breakdown.” Philip K. Dick’s writing is an example of such a breakthrough, not only in the sense of a deconstruction of the SF novel, but also of a breaking through the psychological and perceptual confines imposed on us by capitalism.

For the repression of the individual under capitalism goes beyond the obvious economic and military machinery of imperialism or the internal police control which Dick has frequently denounced in his public letters and speeches. It also functions in a more subtle and dangerous way through the control and direction of our forms of perception and thought, making a radically different reality either unthinkable or horribly monstrous. The well-known SF film, The Forbidden Planet (1956), for instance, is a classic presentation of the theme of the “monsters of the id,” those libidinal energies which (from the notion of “original sin” to the contemporary theories of man’s innate aggressiveness), we have been taught to fear and distrust, which society seeks to dominate and control, and which are unleashed from the unconscious whenever the individual’s conscious vigilance is relaxed. Unlike this film which contains an explicit warning against the unbinding of those forces, Van Vogt’s Voyage of The Space Beagle reveals a more ambiguous attitude towards that repression. For what is striking about Van Vogt’s novel (especially in view of his expressed political philosophy) is not so much the voyage, which is both a voyage of self-discovery and the familiar SF theme for the need for synthesis and integration of different scientific methods and disciplines in order to meet the challenges of a changing world, but the narrative of a series of contacts between humans and hostile space creatures. Like the monsters of The Forbidden Planet , these creatures are symbols of the raw, unrepressed libidinal energies which threaten the fabric and smooth functioning of capitalism. Yet in his presentation of these monsters we can detect as well an implicit (or illicit) desire for their force and power which contradicts the novel’s explicit message of science containing those threats. During each confrontation in Van Vogt’s novel, the reader looks for a time through the monster’s eyes, feeling and perceiving reality as the monster experiences it. This identification, however brief, provokes our admiration and envy. To an even higher degree, this is the case in the emphatic understanding of what it would be like to be a Loper in Simak’s City , where almost the entire population of Earth emigrates to Jupiter when offered the chance of becoming such a monster.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Ubik»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Ubik» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Ubik» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.