“Care for a Lucky Strike?” the girl asked him, extending her pack toward him. “ ‘They’re toasted,’ as the slogan goes. The phrase ‘L.S.M.F.T.’ won’t come into existence until—”

Joe said, “My name is Joe Chip.”

“Do you want me to tell you my name?”

“Yes,” he grated, and shut his eyes; he couldn’t speak any further, for a time anyhow. “Do you like Des Moines?” he asked her presently, concealing his hand from her. “Have you lived here a long time?”

“You sound very tired, Mr. Chip,” the girl said.

“Oh, hell,” he said, gesturing. “It doesn’t matter.”

“Yes, it does.” The girl opened her purse, rummaged briskly within it. “I’m not a deformation of Jory’s; I’m not like him—” She indicated the driver. “Or like these little old stores and houses and this dingy street, all these people and their neolithic cars. Here, Mr. Chip.” From her purse she brought an envelope, which she passed to him. “This is for you. Open it right away; I don’t think either of us should have delayed so long.”

With leaden fingers he tore open the envelope.

In it he found a certificate, stately and ornamented. The printing on it, however, swam; he was too weary now to read. “What’s it say?” he asked her, laying it down on his lap.

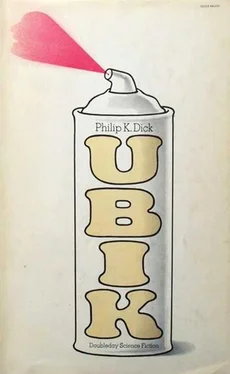

“From the company that manufactures Ubik,” the girl said. “It is a guarantee, Mr. Chip, of a free, lifetime supply, free because I know your problem regarding money, your, shall we say, idiosyncrasy. And a list, on the reverse, of all the drugstores which carry it. Two drugstores—and not abandoned ones—in Des Moines are listed. I suggest we go to one first, before we eat dinner. Here, driver.” She leaned forward and handed the driver a slip of paper already written out. “Take us to this address. And hurry; they’ll be closing soon.”

Joe lay back against the seat, panting for breath.

“We’ll make it to the drugstore,” the girl said, and patted his arm reassuringly.

“Who are you?” Joe asked her.

“My name is Ella. Ella Hyde Runciter. Your employer’s wife.”

“You’re here with us,” Joe said. “On this side; you’re in cold-pac.”

“As you well know. I have been for some time,” Ella Runciter said. “Fairly soon I’ll be reborn into another womb, I think. At least, Glen says so. I keep dreaming about a smoky red light, and that’s bad; that’s not a morally proper womb to be born into.” She laughed a rich, warm laugh.

“You’re the other one,” Joe said. “Jory destroying us, you trying to help us. Behind you there’s no one, just as there’s no one behind Jory. I’ve reached the last entities involved.”

Ella said caustically, “I don’t think of myself as an ‘entity’, I usually think of myself as Ella Runciter.”

“But it’s true,” Joe said.

“Yes.” Somberly, she nodded.

“Why are you working against Jory?”

“Because Jory invaded me,” Ella said. “He menaced me in the same way he’s menaced you. We both know what he does; he told you himself, in your hotel room. Sometimes he becomes very powerful; on occasion, he manages to supplant me when I’m active and trying to talk to Glen. But I seem to be able to cope with him better than most half-lifers, with or without Ubik. Better, for instance, than your group, even acting as a collective.”

“Yes,” Joe said. It certainly was true. Well proved.

“When I’m reborn,” Ella said, “Glen won’t be able to consult with me any more. I have a very selfish, practical reason for assisting you, Mr. Chip; I want you to replace me. I want to have someone whom Glen can ask for advice and assistance, whom he can lean on. You will be ideal; you’ll be doing in half-life what you did in full-life. So, in a sense, I’m not motivated by noble sentiments; I saved you from Jory for a good common-sense reason.” She added, “And god knows I detest Jory.”

“After you’re reborn,” Joe said, “I won’t succumb?’

“You have your lifetime supply of Ubik. As it says on the certificate I gave you.”

Joe said, “Maybe I can defeat Jory.”

“Destroy him, you mean?” Ella pondered. “He’s not invulnerable. Maybe in time you can learn ways to nullify him. I think that’s really the best you can hope to do; I doubt if you can truly destroy him—in other words consume him—as he does to half-lifers placed near him at the moratorium.”

“Hell,” Joe said. “I’ll tell Glen Runciter the situation and have him move Jory out of the moratorium entirely.”

“Glen has no authority to do that.”

“Won’t Schoenheit von Vogelsang—”

Ella said, “Herbert is paid a great deal of money annually, by Jory’s family, to keep him with the others and to think up plausible reasons for doing so. And—there are Jorys in every moratorium. This battle goes on wherever you have half-lifers; it’s a verity, a rule, of our kind of existence.” She lapsed into silence then; for the first time he saw on her face an expression of anger. A ruffled, taut look that disturbed her tranquility. “It has to be fought on our side of the glass,” Ella said. “By those of us in half-life, those that Jory preys on. You’ll have to take charge, Mr. Chip, after I’m reborn. Do you think you can do that? It’ll be hard. Jory will be sapping your strength always, putting a burden on you that you’ll feel as—” She hesitated. “The approach of death. Which it will be. Because in half-life we diminish constantly anyhow. Jory only speeds it up. The weariness and cooling-off come anyhow. But not so soon.”

To himself Joe thought, I can remember what he did to Wendy. That’ll keep me going. That alone.

“Here’s the drugstore, miss,” the driver said. The square, upright old Dodge wheezed to the curb and parked.

“I won’t go in with you,” Ella Runciter said to Joe as he opened the door and crept shakily out. “Goodby. Thanks for your loyalty to Glen. Thanks for what you’re going to be doing for him.” She leaned toward him, kissed him on the cheek; her lips seemed to him ripe with life. And some of it was conveyed to him; he felt slightly stronger. “Good luck with Jory.” She settled back, composed herself sedately, her purse on her lap.

Joe shut the cab door, stood, then made his way haltingly into the drugstore. Behind him the cab thud-thudded off; he heard but did not see it go.

Within the solemn, lamplit interior of the drugstore a bald pharmacist wearing a formal dark vest, bow tie and sharply pressed sharkskin trousers, approached him. “Afraid we’re closing, sir. I was just coming to lock the door.”

“But I’m in,” Joe said. “And I want to be waited on.” He showed the pharmacist the certificate which Ella had given him; squinting through his round, rimless glasses, the pharmacist labored over the gothic printing. “Are you going to wait on me?” Joe asked.

“Ubik,” the pharmacist said. “I believe I’m out of that. Let me check and see.” He started off.

“Jory,” Joe said.

Turning his head the pharmacist said, “Sir?”

“You’re Jory,” Joe said. I can tell now, he said to himself. I’m learning to know him when I encounter him. “You invented this drugstore,” he said, “and everything in it except for the spray cans of Ubik. You have no authority over Ubik; that comes from Ella.” He forced himself into motion; step by step he edged his way behind the counter to the shelves of medical supplies. Peering in the gloom over one shelf after the other, he tried to locate the Ubik. The lighting of the store had dimmed; the antique fixtures were fading.

“I’ve regressed all the Ubik in this store,” the pharmacist said in a youthful, high-pitched Jory voice. “Back to the liver and kidney balm. It’s no good now.”

Читать дальше