Reaching the lobby, he gazed around him, at the people, the great chandelier overhead. Jory, in many respects, had done a good job, despite the reversion to these older forms. Real, he thought, experiencing the floor beneath his feet. I can’t get over it.

He thought, Jory must have had experience. He must have done this many times before.

Going to the hotel desk, he said to the clerk, “You have a restaurant that you’d recommend?”

“Down the street,” the clerk said, pausing in his task of sorting mail. “To your right. The Matador. You’ll find it excellent, sir.”

“I’m lonely,” Joe said, on impulse. “Does the hotel have any source of supply? Any girls?”

The clerk said in a clipped, disapproving voice, “Not this hotel, sir; this hotel does not pander.”

“You keep a good clean family hotel,” Joe said.

“We like to think so, sir.”

“I was just testing you,” Joe said. “I wanted to be sure what kind of hotel I was staying in.” He left the counter, recrossed the lobby, made his way down the wide marble stairs, through the revolving door and onto the pavement outside.

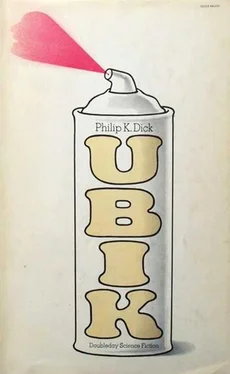

Wake up to a hearty, lip-smacking bowlful of nutritious, nourishing Ubik toasted flakes, the adult cereal that’s more crunchy, more tasty, more yummmish. Ubik breakfast cereal, the whole-bowl taste treat! Do not exceed recommended portion at any one meal.

The diversity of cars impressed him. Many years represented, many makes and many models. The fact that they mostly came in black could not be laid at Jory’s door; this detail was authentic.

But how did Jory know it?

That’s peculiar, he thought; Jory’s knowledge of the minutiae of 1939, a period in which none of us lived—except Glen Runciter.

Then all at once he realized why. Jory had told the truth; he had constructed—not this world—but the world, or rather its phantasmagoric counterpart, of their own time. Decomposition back to these forms was not of his doing; they happened despite his efforts. These are natural atavisms, Joe realized, happening mechanically as Jory’s strength wanes. As the boy says, it’s an enormous effort. This is perhaps the first time he has created a world this diverse, for so many people at once. It isn’t usual for so many half-lifers to be interwired.

We have put an abnormal strain on Jory, he said to himself. And we paid for it.

A square old Dodge taxi sputtered past; Joe waved at it, and the cab floundered noisily to the curb. Let’s test out what Jory said, he said to himself, as to the early boundary of this quasi world now. To the driver he said, “Take me for a ride through town; go anywhere you want. I’d like to see as many streets and buildings and people as possible, and then, when you’ve driven through all of Des Moines, I want you to drive me to the next town and we’ll see that.”

“I don’t go between towns, mister,” the driver said, holding the door open for Joe. “But I’ll be glad to drive you around Des Moines. It’s a nice city, sir. You’re from out of state, aren’t you?”

“New York,” Joe said, getting inside the cab.

The cab rolled back out into traffic. “How do they feel about the war back in New York?” the driver asked presently. “Do you think we’ll be getting into it? Roosevelt wants to get us—”

“I don’t care to discuss politics or the war,” Joe said harshly.

They drove for a time in silence.

Watching the buildings, people and cars go by, Joe asked himself again how Jory could maintain it all. So many details, he marveled. I should be coming to the edge of it soon; it has to be just about now.

“Driver,” he said, “are there any houses of prostitution here in Des Moines?’

“No,” the driver said.

Maybe Jory can’t manage that, Joe reflected. Because of his youth. Or maybe he disapproves. He felt, all at once, tired. Where am I going? he asked himself. And what for? To prove to myself that what Jory told me is true? I already know it’s true; I saw the doctor wink out. I saw Jory emerge from inside Don Denny; that should have been enough. All I’m doing this way is putting more of a load on Jory, which will increase his appetite. I’d better give up, he decided. This is pointless.

And, as Jory had said, the Ubik would be wearing off anyhow. This driving around Des Moines is not the way I want to spend my last minutes or hours of life. There must be something else.

Along the sidewalk a girl moved in a slow, easy gait; she seemed to be window-shopping. A pretty girl, with gay, blond pigtails, wearing an unbuttoned sweater over her blouse, a bright red skirt and high-heeled little shoes. “Slow the cab,” he instructed the driver. “There, by that girl with the pigtails.”

“She won’t talk to you,” the driver said. “She’ll call a cop.”

Joe said, “I don’t care.” It hardly mattered at this point.

Slowing, the old Dodge bumbled its way to the curb; its tires protested as they rubbed against the curb. The girl glanced up.

“Hi, miss,” Joe said.

She regarded him with curiosity; her warm, intelligent, blue eyes widened a little, but they showed no aversion or alarm. Rather, she seemed slightly amused at him. But in a friendly way. “Yes?” she said.

“I’m going to die,” Joe said.

“Oh, dear,” the girl said, with concern. “Are you—”

“He’s not sick,” the driver put in. “He’s been asking after girls; he just wants to pick you up.”

The girl laughed. Without hostility. And she did not depart.

“It’s almost dinnertime,” Joe said to her. “Let me take you to a restaurant, the Matador; I understand that’s nice.” His tiredness now had increased; he felt the weight of it on him, and then he realized, with muted, weary horror, that it consisted of the same fatigue which had attacked him in the hotel lobby, after he had shown the police citation to Pat. And the cold. Stealthily, the physical experience of the cold-pac surrounding him had come back. The Ubik is beginning to wear off, he realized. I don’t have much longer.

Something must have showed in his face; the girl walked toward him, up to the window of the cab. “Are you all right?” she asked.

Joe said, with effort, “I’m dying, miss.” The wound on his hand, the teeth marks, had begun to throb once more. And were again becoming visible. This alone would have been enough to fill him with dread.

“Have the driver take you to the hospital,” the girl said.

“Can we have dinner together?” Joe asked her.

“Is that what you want to do?” she said. “When you’re—whatever it is. Sick? Are you sick?” She opened the door of the cab then. “Do you want me to go with you to the hospital? Is that it?”

“To the Matador,” Joe said. “We’ll have braised fillet of Martian mole cricket.” He remembered then that that imported delicacy did not exist in this time period. “Market steak,” he said. “Beef. Do you like beef?”

Getting into the cab, the girl said to the driver, “He wants to go to the Matador.”

“Okay, miss,” the driver said. The cab rolled out into traffic once more. At the next intersection the driver made a U-turn; now Joe realized, we are on our way to the restaurant. I wonder if I’ll make it there. Fatigue and cold had invaded him completely; he felt his body processes begin to close down, one by one. Organs that had no future; the liver did not need to make red blood cells, the kidneys did not need to excrete wastes, the intestines no longer served any purpose. Only the heart, laboring on, and the increasingly difficult breathing; each time he drew air into his lungs he sensed the concrete block that had situated itself on his chest. My gravestone, he decided. His hand, he saw, was bleeding again; thick, slow blood appeared, drop by drop.

Читать дальше