With the screen, we could attune that mind’s vibration to this sector in spacetime; here, now, between the poles of the screen. Then, space annihilated by the matrix, we could shift the energons of mind and body and bring them here.

My brain played with words like hyperspace and dimension-travel and matter-transmitter, but those were only words.

I dropped into the chair below the screen, bending to calibrate the controls to my own cerebral pattern. I fiddled fussily with the dial, not looking up. “You’ll have to cut out the monitor screen, Callina.”

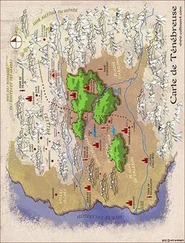

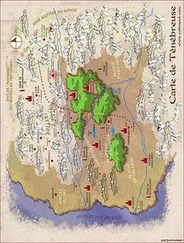

She crossed the room and touched a series of studs; the bank of lights winked out, shunting every matrix on Dark-over out of this monitor. “There’s a bypass relay through the Arilinn tower,” she explained.

A grill crackled and sent out a tiny staccato signal. Callina listened a moment, then said, “Yes, I know, Maruca. But we have cut out the main circuits. You’ll have to hold the energons in Arilinn tonight.”

She waited; then rapped out, “Put up a third-level barrier around Thendara! That is a command from Comyn; acknowledge and comply!” She turned away, sighing.

“That girl is the noisiest telepath on the planet,” she said. “I wish any other Keeper had been at Arilinn tonight. There are a few who can cut through a third-level barrier, but if I asked for a fourth—” she sighed. I understood; a fourth-level barrier would have alerted every telepath on the planet to the fact that something was going on in the Comyn Castle.

We’d chance it. She took her place before the matrix, and I blanked my mind against the screen. I shut out sense impressions, reaching to adjust the psychokinetic waves into the pattern we wanted. What sort of alien would suit us? But without volition on my part, a pattern laid itself down.

I saw, in the instant before my optic nerve overloaded and went out, the dim symbols of a pattern in the matrix; then I went blind and deaf in that instant of overload that is always terrifying.

Gradually, without external senses, I found orientation in the screen. My mind, extended to astronomical proportions, swept incredible distances; traversed, in fractional seconds, whole parsecs and galaxies of subjective spacetime. There came vague touches of consciousness, fragments of thought, emotions that floated like shadows — the flotsam of the mental universe.

Then, before I felt contact, I saw the white-hot flare in the screen. Somewhere another mind had fitted into the pattern. We had cast it out through time and space, like a net, and when we met a mind that fitted, it had been snared.

I swung out, bodiless, divided into a billion subjective fragments, extended over a vast gulf of spacetime. If anything happened, I would never get back into my body, but would float in the spacetime curve forever.

With infinite caution, I poured myself into the alien mind. There was a short but terrible struggle; it was embedded, enlaced in mine. The world was a holocaust of molten-glass fire and color. The air writhed with cold flames, and the glow on the screen was a shadow and then a clearing darkness and then an image, captive in my mind, and then-Light tore at my eyes. A ripping shock slammed through my brain, the floor seemed to rock and the walls to crash together and apart, and Callina was flung, reeling, against me as the energons seared the air and my brain.

Half stunned, but conscious, I looked up at Callina. The alien mind was torn free of mine. The screen was blank.

And in a crumpled heap on the floor, at the base of the Screen, where she had fallen, lay a slender, dark-haired girl.

Unsteadily, Callina knelt beside the crumpled form. I followed slowly, and bent over beside her.

“She isn’t dead?”

“Of course not.” Callina looked up. “But that was terrible, even for us. What do you think it was like for her? She’s in shock.”

The girl was lying on her side, one arm across her face.

Soft brown hair, falling forward, hid her features. I brushed it lightly back — then stopped, my hand still touching her cheek, in dazed bewilderment.

“It’s Linnell,” Callina choked. “Linnell!”

Lying on the cold floor was the girl on the spaceport; the girl I had seen in my first confused moments in Thendara.

For a moment, even knowing as I did what had happened, I thought my mind would give way. The transition had taken its toll of me, too. Every nerve in my body ached.

“What have we done?” Callina moaned. “ What have we done ?”

I held her tight. Of course, I thought; of course. Linnell was near; she was close to both of us; we had both been talking, and thinking of Linnell tonight. And yet…

“You know Cherillys’ two point law?” I tried to put it into simple words. “Everything, everywhere, except a matrix, exists in one exact duplicate. This chair, my cloak, the screwdriver on your table, the public fountain in Port Chicago — everything in the universe exists in one exact molecular duplicate. Nothing is unique except a matrix; but there are no three things alike in the universe.”

“Then this is — Linnell’s twin?”

“More than that. Only once in a million years or so would duplicates also be twins. This is her real twin. Same fingerprints. Same retinal eye patterns. Same betagraphs and blood type. She won’t be much like Linnell in personality, probably, because the duplicates of Linnell’s environment are scattered all over the galaxy. But in flesh and blood, they’re identical. Even her chromosomes are identical with Linnell’s.

I took up the girl’s wrist and turned it over. The curious matrix mark of the Comyn was duplicated there. “Birthmark,” I said, “but the effect is identical in her flesh. See?”

I stood up. Callina stared and stared. “Can she live in this environment, then?”

“Why not? If she’s Linnell’s duplicate, she breathes oxygen in the same ratio we do, and her internal organs are adjusted to about the same gravity.”

“Can you carry her? She’ll get another bad shock if she wakes up in this place!” Callina indicated the matrix equipment.

I grinned humorlessly.- “She’ll get one anyway.” But I managed to scoop her up, one-armed. She was frail and light, like Linnell. Callina held curtains aside for me, showed me where to lay her. I covered the girl, for it was cold, and Callina murmured, “I wonder where she comes from?”

“She was born on a world with gravity about the same as Darkover, which narrows it considerably. Vialles, Wolf, even Terra. Or, of course, some planet we never heard of.” Her speech had impressed me as Terran; but I hadn’t told Callina about that episode on the spaceport, and didn’t intend to. “Let’s leave her to sleep off the shock, and get some sleep Ourselves.”

Callina stood in the door with me, her hands locked on mine. She looked haggard and worn, but lovely to me after the shared danger, shared weariness. I bent and kissed her.

“Callina,” I whispered. It was half a question, but she freed her hand gently and I did not press her. She was right. We were both desperately exhausted. It would have been raving insanity. I put her gently away and went out without looking back. It was raining hard, but until the wet red morning rose sunlessly over Thendara I paced the courtyard, restless, and the drops on my face were not all rain.

Toward dawn I fought back to self-control, and went back to the Keeper’s Tower. I was afraid that without Callina at my side I would not find a way into the blue-ice room, or that Ashara had vanished into some inaccessible place. But she was there; and such was the illusion of the frosty light, or of my tired eyes, that she seemed younger, less guarded; like a strange, icy, inhuman Callina. My brain almost refused to think clearly, but I finally managed to formulate my plea.

Читать дальше