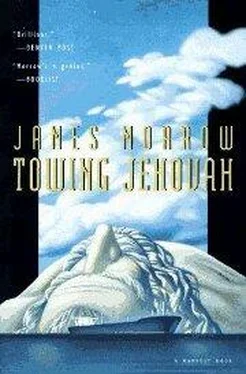

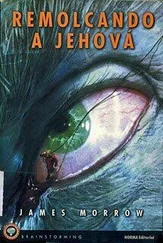

Van Horne stood atop the mahogany bar, outfitted in his dress blues, the sobriety of the dark serge intermittently relieved by brass buttons and gold piping. “Well, sailors, we’ve all seen it, we’ve all smelled it,” he told the assembled company. “Believe me, there’s never been such a corpse before, none so large, none so important.”

Third Mate Dolores Haycox shifted her weight from one tree-stump leg to the other. “A corpse, sir? You say it’s a corpse ?”

A corpse? thought Neil.

“A corpse,” said Van Horne. “Now — any guesses?”

“A whale?” ventured gnomish little Charlie Horrocks, the pumpman.

“No whale could be that huge, could it?”

“I suppose not,” said Horrocks.

“A dinosaur?” offered Isabel Bostwick, an Amazonian wiper with buck teeth and a buzz cut.

“You’re not thinking on the right scale.”

“An outer-space alien?” said the alcoholic bos’n, Eddie Wheatstone, his face so ravaged by acne it looked like a used archery target.

“No. Not an outer-space alien — not exactly. Our friend Father Thomas has a theory for you.”

Slowly, with great dignity, the priest walked in a wide loop, circling the company, corralling them with his stride. “How many of you believe in God?”

Rumblings of surprise filled the wardroom, echoing off the teakwood. Leo Zook’s hand shot up. Cassie Fowler burst into giggles.

“Depends on what you mean by God,” said Lianne Bliss.

“Don’t analyze, just answer.”

One by one, the sailors reached skyward, fingers wiggling, arms swaying, until the wardroom came to resemble a garden of anemones. Neil joined the consensus. Why not? Didn’t he have his enigmatic something-or-other, his En Sof, his God of the four A.M. watch? He counted a mere half-dozen atheists: Fowler, Wheatstone, Bostwick, a corpulent demac named Stubby Barnes, a spidery black pastry chef named Willie Pindar, and Ralph Mungo, the decrepit guy from the union hall with the I LOVE BRENDA tattoo — and of these six only Fowler seemed confident, going so far as to thrust both hands into the pockets of her khaki shorts.

“I believe in God, the Father Almighty,” said Leo Zook, “maker of heaven and earth, and in His only Son, Jesus Christ our Lord…”

The priest cleared his throat, his Adam’s apple bumping against his Roman collar. “Keep your hand up if you think that God is essentially a spirit — an invisible, formless spirit.”

Not one hand dropped.

“Okay. Now. Keep your hand up if you think that, when all is said and done, our Creator is quite a bit like a person — a powerful, stupendous, gigantic person, complete with bones, muscles…”

The vast majority of arms descended, Neil’s among them. Spirit and flesh: God couldn’t be both. He wondered about the three sailors whose arms remained aloft.

“Now you’re talking about Jesus Christ,” said Zook, his hand fluttering about like a drunken hummingbird.

“No,” said the priest. “I’m not talking about Jesus Christ.”

A falling sensation overcame Neil. Reaching into his jeans, he squeezed the bronze medal his grandfather had received for smuggling refugees to the nascent nation of Israel. “Wait a minute, Father, sir. Are you saying… ?” Gulping, he repeated himself. “Are you saying… ?”

“Yes. I am.”

Whereupon Father Thomas lifted a gleaming white ball from the billiard table, tossed it straight up, caught it, and proceeded to relate the most grotesque and disorienting story Neil had heard since learning that the Datsun containing his parents had fallen between the spans of an open drawbridge in Woods Hole, Cape Cod, and vanished beneath the mud. Among its assorted absurdities, the priest’s tale included not only a dead deity and a prescient computer, but also weeping angels, confused cardinals, mourning narwhals, and a hollowed-out iceberg jammed against the island of Kvitoya.

As soon as he was finished, Dolores Haycox jabbed her thick index finger toward Van Horne. “You told us it was asphalt,” she whined. “Asphalt, you said.”

“I lied,” the captain admitted.

From the middle of the crowd, the squat and wan chief engineer, Crock O’Connor, piped up. “I’d like to say something,” he drawled, wiping his oily hands on his Harley-Davidson T-shirt. Steam burns dappled his cheeks and arms. “I’d like to say that, in all my thirty years at sea, I never heard such a pile of pasteurized, homogenized, cold-filtered horseshit.”

The priest’s voice remained measured and calm. “You may be correct, Mr. O’Connor. But then how are we to interpret the evidence currently floating off our starboard quarter?”

“A snare set by Satan,” Zook replied instantly. “He’s testing our faith.”

“A UFO made of flesh,” said Chief Steward Sam Follingsbee.

“The Loch Ness Monster,” said Karl Jaworski.

“One of them government biology experiments,” said Ralph Mungo, “gotten way outta hand.”

“I’ll bet it’s just rubber,” said James Echohawk.

“Yeah,” said Willie Pindar. “Rubber and fiberglass and such…”

“Okay, maybe a deity,” said Bud Ramsey, the chicken-necked, weasel-faced second assistant engineer, “but certainly not God Himself.”

Silence settled over the wardroom, heavy as a kedge anchor, thick as North Sea fog.

The sailors of the Valparaíso looked at each other, slowly, with pained eyes.

God’s dead body.

Oh, yes.

“But is He really gone?” asked Horrocks in a high, gelded voice. “Totally and completely gone?”

“The OMNIVAC predicted a few surviving neurons,” said Father Thomas, “but I believe it’s working with faulty data. Still, each of us has the right to entertain his own private hopes.”

“Why doesn’t the sky turn black?” demanded Jaworski. “Why doesn’t the sea dry up and the sun blink out? Why aren’t the mountains crumbling, forests toppling over, stars falling from heaven?”

“Evidently we’re living in a noncontingent, Newtonian sort of universe,” Father Thomas replied. “The clock continues ticking even after the Clockmaker departs.”

“Okay, okay, but what’s the reason for His death?” asked O’Connor. “There’s gotta be a reason.”

“At the moment, the mystery of our Creator’s passing is as dense as the mystery of His advent. Gabriel urged me to keep thinking about the problem. He believed that, by journey’s end, the answer would become clear.”

What followed was a theological free-for-all, the only time, Neil surmised, that a supertanker’s entire crew had engaged in a marathon discussion of something other than professional sports. Dinnertime came and went. The new moon rose. The sailors grew schizoid, a company of Jekyll-and-Hydes, their bouts of Weltschmerz alternating with fresh denials (a CIA plot, a sea serpent, an inflatable dummy, a movie prop), then back to Weltschmerz, then more denials still (communism’s last gasp, the Colossus of Rhodes emerging from the seabed, a distraction concocted by the Trilateral Commission, a faз ade concealing something truly bizarre). Neil’s own reactions bewildered him. He was not sad — how could he be sad? Losing this particular Supreme Being was like losing some relative you barely knew, the shadowy Uncle Ezra who gave you a fifty-dollar bill at your bar mitzvah and forthwith disappeared. What Neil experienced just then was freedom. He’d never believed in the stern, bearded God of Abraham, yet in some paradoxical way he’d always felt accountable to that nonexistent deity’s laws. But now YHWH wasn’t watching. Now the rules no longer applied.

“Guess what, sailors?” Van Horne jumped from the mahogany bar to the Oriental rug. “I’m canceling all duties for the next twenty-four hours. No chipping, no painting — and you won’t lose one red cent in pay.” Never before in nautical history, Neil speculated, had such an announcement failed to provoke a single cheer. “From this moment until 2200,” said the captain, “Father Thomas and Sister Miriam will be available in their cabins for private consultations. And tomorrow — well, tomorrow we start doing what’s expected of us, right? How about it? Are we merchant mariners? Are we ready to move the goods? Can you give me an aye on that?”

Читать дальше