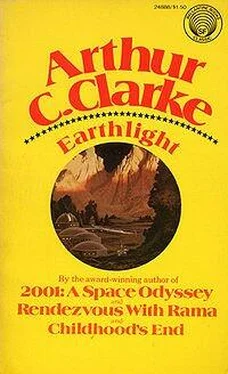

Arthur Clarke - Earthlight

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Arthur Clarke - Earthlight» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1955, ISBN: 1955, Издательство: Muller, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Earthlight

- Автор:

- Издательство:Muller

- Жанр:

- Год:1955

- ISBN:0-151-27225-5

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Earthlight: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Earthlight»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is the story of this emerging conflict.

Earthlight — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Earthlight», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

There was, of course, an obvious answer to such weapons. The electric and magnetic fields which produced them could also be used for their dispersion, converting them from annihilating beams into a harmless, scattered spray.

More effective, but more difficult to build, were the weapons using pure radiation. Yet even here, both Earth and the Federation had succeeded. It remained to be seen which had done the better job—the superior science of the Federation, or the greater productive capacity of Earth.

Commodore Brennan was well aware of all these factors as his little fleet converged upon the Moon. Like all commanders, he was going into action with fewer resources than he would have wished. Indeed, he would very much have preferred not to be going into action at all.

The converted liner Eridanus and the largely rebuilt freighter Lethe —once listed in Lloyd’s register as the Morning Star and the Rigel —would now be swinging in between Earth and Moon along their carefully plotted courses. He did not know if they still had the element of surprise. Even if they had been detected, Earth might not know of the existence of this third and largest ship, the Acheron. Brennan wondered what romantic with a taste for mythology was responsible for these names—probably Commissioner Churchill, who made a point of emulating his famous ancestor in as many ways as he possibly could. Yet they were not inappropriate. The rivers of Death and Oblivion—yes, these were things they might bring to many men before another day had passed.

Lieutenant Curtis, one of the few men in the crew who had actually spent most of his working life in space, looked up from the communications desk.

“Message just picked up from the Moon, sir. Addressed to us.”

Brerman was badly shaken. If they had been spotted, surely their opponents were not so contemptuous of them that they would freely admit the fact! He glanced quickly at the signal, then gave a sigh of relief.

OBSERVATORY TO FEDERATION. WISH TO REMIND YOU OF EXISTENCE IRREPLACEABLE INSTRUMENTS PLATO. ALSO ENTIRE OBSERVATORY STAFF STILL HERE. MACLAURIN. DIRECTOR.

“Don’t frighten me like that again, Curtis,” said the commodore. “I thought you meant it was beamed at me. I’d hate to think they could detect us this far out.”

“Sorry, sir. It’s just a general broadcast. They’re still sending it out on the Observatory wavelength.”

Brennan handed the signal over to his operations controller, Captain Merton.

“What do you make of this? You worked there, didn’t you?”

Merton smiled as he read the message.

“Just like Maclaurin. Instruments first, staff second. I’m not too worried. I’ll do my damnedest to miss him. A hundred kilometers isn’t a bad safety margin, when you come to think of it. Unless there’s a direct hit with a stray, they’ve nothing to worry about. They’re pretty well dug in, you know.”

The relentless hand of the chronometer was scything away the last minutes. Still confident that his ship, encased in its cocoon of night, had not yet been detected, Commodore Brennan watched the three sparks of his fleet creep along their appointed tracks in the plotting sphere. This was not a destiny he had ever imagined would be his—to hold the fate of worlds within his hands.

But he was not thinking of the powers that slumbered in the reactor banks, waiting for his command. He was not concerned with the place he would take in history, when men looked back upon this day. He only wondered, as had all who had ever faced battle for the first time, where he would be this same time tomorrow.

Less than a million kilometers away, Carl Steffanson sat at a control desk and watched the image of the sun, picked up by one of the many cameras that were the eyes of Project Thor. The group of tired technicians standing around him had almost completed the equipment before his arrival; now the discriminating units he had brought from Earth in such desperate haste had been wired into the circuit.

Steffanson turned a knob, and the sun went out. He flicked from one camera position to another, but all the eyes of the fortress were equally blind. The coverage was complete.

Too weary to feel any exhilaration, he leaned back in his seat and gestured toward the controls.

“It’s up to you now. Set it to pass enough light for vision, but to give total rejection from the ultra-violet upward. We’re sure none of their beams carry any effective power much beyond a thousand Angstroms. They’ll be very surprised when all their stuff bounces off. I only wish we could send it back the way it came.”

“Wonder what we look like from outside when the screen’s on?” said one of the engineers.

“Just like a perfectly reflecting mirror. As long as it keeps reflecting, we’re safe against pure radiation. That’s all I can promise you.”

Steffanson looked at his watch.

“If Intelligence is correct, we have about twenty minutes to spare. But I shouldn’t count on it.”

“At least Maclaurin knows where we are now,” said Jamieson as he switched off the radio. “But I can’t blame him for not sending someone to pull us out.”

“Then what do we do now?”

“Get some food,” Jamieson answered, walking back to the tiny galley. “I think we’ve earned it, and there may be a long walk ahead of us.”

Wheeler looked nervously across the plain, to the distant but all too clearly visible dome of Project Thor. Then his jaw dropped and it was some seconds before he could believe that his eyes were not playing tricks on him.

“Sid!” he called. “Come and look at this!”

Jamieson joined him at a rush, and together they stared out toward the horizon. The partly shadowed hemisphere of the dome had changed its appearance completely. Instead of a thin crescent of light, it now showed a single dazzling star, as though the image of the sun was being reflected from a perfectly spherical mirror surface.

The telescope confirmed this impression. The dome itself was no longer visible; its place seemed to have been taken by this fantastic silver apparition. To Wheeler it looked exactly like a great blob of mercury sitting on the skyline.

“I’d like to know how they’ve done that,” was Jamieson’s un-excited comment. “Some kind of interference effect, I suppose. It must be part of their defense system.”

“We’d better get moving,” said Wheeler anxiously. “I don’t like the look of this. It feels horribly exposed up here.”

Jamieson had started throwing open cupboards and pulling out stores. He tossed some bars of chocolate and packets of compressed meat over to Wheeler.

“Start chewing some of this,” he said. “We won’t have time for a proper meal now. Better have a drink as well, if you’re thirsty. But don’t take too much—you’ll be in that suit for hours, and these aren’t luxury models.”

Wheeler was doing some mental arithmetic. They must be about eighty kilometers from base, with the entire rampart of Plato between them and the Observatory. Yes, it would be a long walk home, and they might after all be safer here. The tractor, which had already served them so well, could protect them from a good deal of trouble.

Jamieson toyed with the idea, but then rejected it. “Remember what Steffanson said,” he reminded Wheeler. “He told us to get underground as soon as we could. And he must know what he’s talking about.”

They found a crevasse within fifty meters of the tractor, on the slope of the ridge away from the fortress. It was just deep enough to see out of when they stood upright, and the floor was sufficiently level to lie down. As a slit trench, it might almost have been made to order, and Jamieson felt much happier when he had located it.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Earthlight»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Earthlight» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Earthlight» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.