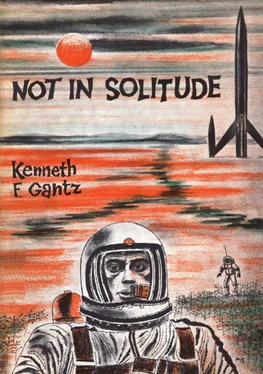

Dane got to the photo plane monitor and switched it into the message circuit on observation deck antenna. A scramble of meaningless lines danced randomly, like a madman’s game of jackstraws.

The Martian was jammed! At least for the moment it was incoherent.

“Colonel Cragg!” he cried. “Are you all right?”

“Get me out from under!” Cragg sang out, loud in the quiet. They lifted McDonald’s body off him.

Cragg stared at the blood on his hands. “I don’t think it’s me.” He felt inside his torn robe. “I don’t think so.”

“Give it full speed and let’s get away fast!” Dane urged. “The Martians’ transmission is all fouled up. Maybe we have stunned it. Now’s our chance.”

They helped Cragg to his feet and supported him while he watched the spasmodically flashing lines in the oscilloscope. He nodded to Dane. “Looks like you hit it right on the head.”

He threw a glance at the angle-of-flight indicator before he raised the phone he had never let go. “Beloit. Give me maximum acceleration as fast as possible. To hell with the damage,” he retorted. “Just give me as much speed as you can as quickly as you can. I want to get out in space. Away out in space. We’ll worry about course later.”

With acceleration the floor became the floor again. Shapes assumed their normal form. The Far Venture was again the familiar world where men stood upright.

FOR AN hour the spacecraft shot up from the planet Cragg let the acceleration grow until the ride felt like an elevator going through the roof.

Once he grinned. “She’s responding perfectly to control. Now we make space, and it’s good-by to your Martian.” Then he sat with his eyes fixed on the command banks while the minutes worked around the clock. The fell radiation had vanished, but the radiomen could not raise Earth.

Finally he spoke to Major Beloit The automatic acceleration control took over, and they stood free of their boots and weights at apparent gravity Earth. Then he said to Dane, “Give me a push. Let’s take a look.”

They went down the lift to 2-low and opened a port. The variegated disk of Mars bulged its green and red shapes of false continents and seas out from the tail cone against the star-spangled blackness.

Cragg pushed out his silver case brusquely at Dane and lighted one of the black stogies for him. Dane marveled at the man’s vitality. If the rough-and-tumble take-off had any physical effect on him, it had been tonic. Cragg put the lighter to his own stogie and breathed out the first cloud of the pungent smoke, his eyes looking over the flame at Dane. “I think we’ve carried it off. Unless your Martian mind has got a long reach when it snaps out of its razzle-dazzle.”

Dane said, “It disturbs me. I can’t feel good about it. I hate to think that we found intelligence on Mars and then maybe destroyed it. Or left it impaired. Maybe insane. It’s a pity we couldn’t make it understand us!”

“Maybe it did.” Cragg said. “Though for its own purposes. Maybe it understood us well enough to know it didn’t want anything we had to bring. Maybe it just didn’t like the idea of change.”

Dane said, “We’ve had quite a history of that on Earth. Either you agree with me or I’ll smash you for your wickedness, which you have already proved by your disagreement with me.”

Cragg looked his stogie over carefully, rotating it in his fingers, inspecting the entire wrapper leaf. “When I was a young man I used to worry a lot about the poor prospects of heresy. The thing that bothered me was that the very idea of change came inevitably from reflective thought, but then the man who reflected couldn’t help choosing some of his reflections as the best ones to believe. The next thing he inevitably did was to believe the others were wrong to believe. From there he had only one more step to take to intolerance and a new orthodoxy.”

He stopped to puff at his failing light. “So we weren’t so far from home on Mars after all. Your Martian’s self-worship of its oneness is not so different from what we call doctrine. We were the heretics on Mars by the very fact of our existence. Why are we surprised? I’m pretty far away from my line, making a speech like that,” he broke off with a deprecatory grin.

Dane shook his head. “Colonel, you’ve been the source of a lot of surprises to me on the Far Venture. Never any more than now.”

“You once labeled me a man of action. I’m pretty sure you didn’t mean it to be any compliment. That what you mean?”

“I underestimated you.”

Cragg shook his head. “I underestimated you more than plenty. A week ago I’d have bet a million you didn’t have the foggiest idea why sometimes you’ve got to make a decision and act on it just like it was one hundred per cent right. Even if you’re not sure of anything else except that it’s high time to do something, one way or the other. Now I’ve seen you act when you couldn’t add up the score. Like the night you brought Noel in. And today. When you took him out again. You turned out to be quite a man of action yourself.

“What I was trying to say about that heresy business,” he went on, “was that I found in the Air Force the simple and satisfying belief in translating objectives into action. If you think about it that way, maybe even the way a guy like you would look at it, a man can have a rational and deliberate belief in the necessity of action. You can believe along with us that action is a right end in itself and that in its larger aspects, in what we call strategy and tactics, it stems from reflection. But what put the icing on my cake for me, what I’m trying to get across, is that I found out, after some time, I admit, that the only fixed Air Force doctrine was the insistence on constant change. The high rating on surprise and divergence from anything that could be predicted. Under the uniform of discipline I found a society of heretics. I don’t say it very well, but that’s what I mean.”

Dane said, “Well, maybe so. But while we’re on the subject of action and decision, I want to tell you it’ll take quite a bit of something to match the way you jerked the Far Venture off the ground of Mars by singlehanded main strength and pure cussedness.”

Cragg wheeled over to a phone. “We’re going on course for Earth,” he said to Dane. “You want to watch?”

Dane was pleasantly warmed by Cragg’s embarrassment. He was going to end up liking the guy if he didn’t watch out.

“You know,” he said, “you’ve maybe put the pieces of this trip back together for me. We’ve all got to hump like hell to avoid a society that organizes us into something like the Martian mind. It’s a lot harder than avoiding the twentieth-century-style totalitarian state. Maybe the real danger is not so much in majorities squelching the heretics but in the simple gravitation of ideals to mass averages of conduct and attainment. After all, the worst threat of the twentieth century wasn’t the nuclear revolution but the population explosion and the taboos that encouraged it. We don’t want any Martian society of the common man stifling the uncommon man. That’s the story I want to take back, but it will gag every wire of Amalgamated.”

“You’d better sugar-coat it a little,” Cragg said dryly.

Hour after hour the Far Venture sped among the star-bright constellations along its straight-line collision course with Earth. Noel’s Automatic Interspatial Navigation Control delicately noted the Doppler shifts in the spectra of its three-star fix under the onrushing speed of the spacecraft and threaded them through its computer, balancing against them the shifting angle of Earth, checking the perturbations of course by sun and planets, firming the constancy of acceleration, juggling and firing the gimbaling steering jets, even seeking the mystic point in space toward which home rolled in its orbit at eighteen miles a second, its own speed slimmed to a trifle by the massive velocities accumulating to the Far Venture.

Читать дальше