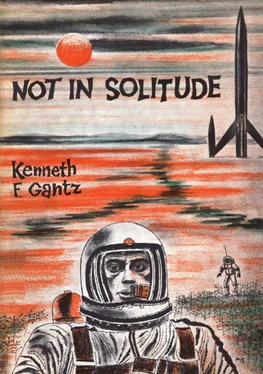

At 0630 daylight was palpably in the air, but they still lived in the ocher folds of the dust storm. “Just let it stop,” McDonald swore. “Just let the damned wind stop blowing and we could see something.”

They could feel no wind, no familiar movement of air, but it was there, three or four miles an hour of it, stirring the feathery dust into vague billows. Like tired smoke. If it would stop, the dust would settle fast in the thin air.

At 0900 they stood together in the haze and agreed that they had come at least five miles. They ought to circle and search. Maybe they had already passed the place. Even if they had been coming out along the right line.

“What’s the use?” Wertz objected. “If the spacecraft is still here, we could be close enough to spit on it and not see it.”

“It’s getting lighter.” Dane tried to sound cheerful. “Maybe it’s settling out.”

“It’s just the sun climbing,” Wertz came back. He pointed up at a brighter spot in the eastern sky.

“We might as well rest awhile and see,” Dane decided. “There’s no use wandering around in it. We can’t go much longer anyway.”

With added gentleness they lowered their burden into the dust. Probably for the last time, Dane thought, not caring much about the fatigue. This is it, he decided. He sat down first and then stretched out full length on the red-dirtying soil, which had long since coated them with its own-claiming color. Waves of relief laved his numb muscles.

HE WAS bouncing around in a boat. Fishing? Somebody was shaking him.

He looked up into broad daylight. At a pressure-helmeted head bending over him. Memory flooded back. The dust had settled!

Then he saw! Behind the transparent visor was the face of Major Noel! He croaked at his microphone.

“Take it easy,” he heard.

Dane sat up. He saw the massive happy shape of the space-craft, geometrical on the red plain. Not a half mile away. He pointed. “Brother, am I glad to see that! We thought for sure that Cragg had left us.”

“He couldn’t,” Major Noel said.

Dane got stiffly to his feet. “Maybe he’s human after all.” He saw that Wertz and Lieutenant McDonald were sitting up, their visors wiped clean of red dust. There were three men with Noel and two carts.

“Couldn’t you hear us calling you?” he blurted. He was appalled now at the fright. Radio blackout, and a man left past hope. Anyway, he was happy. He was happy as all hell, with a great, lightheaded bubbling of spirits. He was thirsty. He was starving. He was everything that was being alive. He decided against the relief tube. In a few minutes they would be rid of the suits. And never again!

Dane, old boy, you made it, he exulted privately. You made it!

Noel said, “I may as well tell you now. The colonel didn’t wait for you. We couldn’t raise you, but the colonel was going anyhow. We couldn’t take off. She wouldn’t fire up. The activators are dead as a last year’s pullet.” He went over to the carts to look at Dr. Pembroke and the others.

It was the way the little major had said it. Dane had no intimate knowledge of the intricate organs of the great space-craft, no familiar kinship with the immense tubular rocket engines or the squat nuclear activators that topped them. Yet a machine was something a mechanic could fix. With time and effort perhaps but, by virtue of his calling, surely. For certainly a machine stood beyond the realm of organic decay or disease or accidental death.

“What’s the matter with them?” he asked.

Noel started the procession off towards the spacecraft. “We don’t know, he said shortly. “We can’t find anything wrong with them. Except that they won’t react for more than ten to twenty per cent power.”

He cut the explanation off as definitely as the slamming of a door and went back to questioning McDonald. Dane decided that only military conversation was desired. He didn’t want to talk anyway. He just wanted to get in the Far Venture and out of the suit as soon as he could. Before he starved to death. No ration pellets this close to the messroom. His watering mouth conjured with the taste image of a thick Air Force steak. With fried potatoes. With pan gravy made from the steak drippings. With ice-cold milk. With homemade bread and yellow butter. Maybe some of the mess cook’s speciality, the baked beans in tomato sauce he always had ready for snacks. It was the best thing about the whole oversized junket, eating in an Air Force mess again, day after day. If he didn’t quit letting his appetite run away, it would be more than a few pounds he had to lose.

Then the airlock was closing and there was the struggle to get out of the suits. Why all the quiet? He saw one or two of the rescuers glance at him and look away without smiling while they jostled out of the stiff suits and passed them up through the manhole for storage, mounting the ladders one by one, manhandling the inert bodies.

“You all quit talking?” he demanded.

Noel nodded at the last two crew members. He waited until they had stowed their gear and started up the ladders. He kept on waiting, his swarthy squeezed-up face contemplating the manual acts of bringing his cigarette to his lips and taking it away again to emit short exhalations of smoke. “To hell with it!” he grunted.

He swung on Dane. “This is it. The top rocket man on board this can is a Pembroke man. Like you. And a civilian. Like you. Now that you’re back on board, do we go?”

Silence swelled thick between them. The little major’s eye did not waver.

“Colonel Cragg?” Dane demanded.

“There are 125 men on this spacecraft,” Noel snapped. “Officers, crew, and scientific personnel. Six were out on the sands. That leaves 119. Besides your friend Vining, that leaves 117 or 118 who think you and Vining messed up the engines.”

“After Colonel Cragg suggested it, I suppose.”

“Suggest hell! He put Vining under arrest.”

Dane stared at him. “How stupid can you fellows get! How could Vining put the engines out? You’ve got rocket engineers on your crew. What’s the matter with them? Wouldn’t they know?”

“That’s just it. They can’t find anything the matter. They’re tearing them all the way down now.”

“Migod!” Dane exclaimed. “What I know about mechanics is how to open a can of sardines, but I do know a man couldn’t do something in a few minutes to those engines that couldn’t be found and fixed in a hurry. He wouldn’t be able to make any noise. He couldn’t use any heavy tools.”

“That’s not what the engineers say. If he is the top rocket man in the United States.”

Dane snorted. “It doesn’t make sense. I want to see this guy Cragg. Now!” Burning up, he reached for the ladder.

Noel said, “Maybe you’d better wait a minute. He’s looking for you, too. He’ll wait. But here’s something you want to think about before you shoot off your mouth. As soon as we spotted you out on the plain this afternoon, the colonel released Vining and put him to work on the engines. That puts your Mr. Vining on somewhat of a spot. You right along with him. If he gets them working, the colonel will probably prosecute the two of you for sabotage or wilfully risking the spacecraft. If we get back to Earth, it’s a trial and maybe prison. Of course if Vining can’t start them, it doesn’t matter much one way or the other.”

His foot on the first rung, Dane turned half around. “What about you? What do you think?”

Noel laughed without mirth. “I know what I want to think. I hope to hell the colonel is right. I want to leave here. And quick. But I’m scared. I don’t figure you’re smart enough for it. I don’t mean you’re dumb. I mean just not sharp smart. I don’t think you’re hard enough to think of giving yourself or Pembroke an ace in the hole with those engines until you could get back here. Vining maybe. But I don’t figure you for it.”

Читать дальше