“Very soon,” Klicks said. “I don’t mean any day now, of course.” He grinned. “But we were aiming for the point in geologic history at which the last dinosaur fossils were found. Our time-travel technology has a fundamental, unavoidable uncertainty about it. The end of the dinosaurs could be as much as three hundred thousand years in the future. Or it could be much, much sooner.”

“What is planet five like?” Diamond-snout asked suddenly.

“Planet five?” I said, lost.

The yellow orbs swung on me. “Yess, yess,” the thing hissed. “Fifth planet from sun.”

“Oh, Jupiter,” I said. “In our time, it’s pretty much the same as we think it always has been: a gas giant, a failed star.” I scratched my ear. “It’s got a nice little ring now, though, which might not have existed in this time. Nothing like Saturn’s, of course, but still pretty neat.”

“Jupiter … oh, see I do,” said the Het. “And between Mars and Jupiter?”

“The asteroid belt, of course.”

“Of course,” said Diamond-snout quickly. The three troodons looked at each other, then turned, their stiff tails swishing through the air; Klicks and I had to step back to avoid being whipped by them. In unison they began to march away.

“Wait a minute,” called Klicks. “Where are you going?”

Diamond-snout swiveled its pointed head back at us for a moment, but the troodons didn’t stop striding away. Giant yellow eyes closed and opened in turns as it rasped, “To attend to our hygiene.”

I was soon to discover the differences between Canada and the United States. My American peers, starting out as assistant professors like me, could expect their first grants in the $30,000 to $40,000 range. I was told that National Research Council of Canada grants begin at about $2,500.

—David Suzuki, Canadian geneticist (1936– )

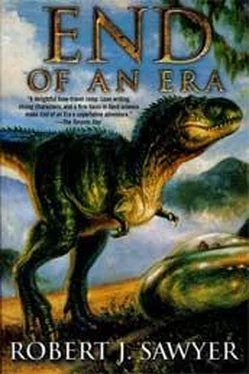

I was born the year Apollo 11 landed on the moon. I was forty-one when the National Research Council of Canada approached me about a time-travel mission. I’d expected our expedition to be along the lines of that moon shot: no expense spared in putting together cutting-edge technology. But there was no big money for pure science anymore—not even in the States, where most of the remaining technological efforts were concentrated on fighting the growing drought in the Midwest. It turned out that big-bucks science had been a purely mid-twentieth-century phenomenon, starting with the Manhattan Project and ending with the fall of the Soviet Union.

The scientific community hadn’t been prepared for this end of an era. But in rapid succession in the early 1990s, the planned Super-Colliding Super Conductor was scrapped, leaving a big hole in the ground where it was supposed to go. About the same time, SETI—the search for extraterrestrial intelligence with radio telescopes—was killed. The International Space Station, originally to be called Freedom , was downsized so much that people quipped it would have to be renamed Space Station Fred , since there wouldn’t be room for the full name on its side—and then, as the various national partners (including Canada) backed out, pleading empty pockets, the few modules that had been assembled in orbit were shut down. The proposed trip to Mars—originally planned for just six years from now, the fiftieth anniversary of Armstrong’s one small step—was likewise chopped. Beg, borrow, and steal became the order of the day in labs throughout the world; big government grants were a fondly remembered thing of the past.

Oh, some military money had trickled in Ching-Mei’s direction for a while. The hawks had seen time travel as strategic, making possible the ultimate in preemptive strikes. They’d provided sufficient funds for Ching-Mei to build a working Huang Effect generator, along with a good-sized power plant to run it. Why, they’d almost finished building Gallifrey —that was the code name for the prototype habitat module that ended up being the Sternberger —when the implications of Ching-Mei’s equations became clear. She’d been quite honest, telling the Department of National Defence from the outset that the amount of energy required for time travel depended on how far back you were going. What she didn’t tell them was that it was, in fact, inversely proportional to the length of time you wanted to travel.

To go back 104 million years, which seemed to be the maximum that the Huang Effect allowed (one of the equations produced a negative number after that point) required virtually no energy at all. To go back 103 million years required a little energy, 102 a little more, and so on. To cast back 67 million years, as we had done, took a huge amount of power. Any attempt to travel back into historical times, a thousand years or so, would take the entire energy output of the Earth for the better part of a century, and to venture back into the last few decades would require the harnessed energy of a small nova.

Time travel, it turned out, was of little good to anyone except paleontologists.

Unfortunately, paleontology has never been a big-money affair. A dig, not a moon shot, became the model for what we were doing. We scraped together what equipment we could, struck sponsorship deals with the private sector, and, slashing expenses as much as possible, came up with just enough to get the two-person test mission going.

Even so, we had to watch every dollar. That’s why we did the Throwback in February, a month in which no sane person would normally visit the Red Deer River valley. Since the air temperature was already thirty degrees below zero Celsius, we saved a bundle cooling the superconducting batteries that were a key part of the Huang Effect generator.

Now that Klicks and I were ready to leave the vicinity of the Sternberger , I would have loved to have some high-tech vehicle with giant springy wheels and dish antennas and nuclear engines. Instead, we had a plain ordinary Jeep, donated because the chairperson of Chrysler Canada had fond memories of his boyhood membership in the ROM’s Saturday Morning Club. There was nothing special about this vehicle; it was just the latest 2013 model from Detroit. It even came with the optional AM/FM stereo and rear-window defogger, both of which had seemed pointless to me.

Getting the Jeep out of its tiny garage was going to be tricky. With the Sternberger high on the crater wall, the vehicle would have to be brought down a very steep incline. We were fortunate that the garage door had ended up facing northwest, pretty much over the outer edge of the crater wall, instead of back toward the bowl of the crater. The Jeep never would have been able to climb out of there, but at least we had a chance of getting it down to ground level in one piece this way.

From inside the Sternberger ’s habitat, I swung open the middle of the three doors along the five-meter-long rear wall. Four steps led down to the tiny garage’s floor, and I squeezed past the left side of the Jeep and slipped into its cab.

Strapping myself in, I looked at the dashboard. I felt like Snoopy in his Sopwith Camel: I check the instruments. They are all there . I’d been practicing in this Jeep for weeks before the Throwback, but it really was true that if you learned to drive with automatic transmission, it was hard to become comfortable with manual later on. I hit the button mounted on the dash, and the garage-door opener—a standard model from Sears—slid the articulate strips of glassteel up.

From my vantage point in the cab, I couldn’t see any ground in front of me. The crater wall fell away so steeply that the Jeep’s hood blocked it from my vision. Instead, I saw the mud plain up ahead and far below. Maybe we could just walk while we’re here…

Читать дальше