“I feel up to it.” Klicks grinned broadly, but it quickly slipped into a patronizing smile. “Brandy, failing to act is a decision in and of itself.”

He’s been reading my diary , I thought briefly, but immediately rejected the idea. It was password-protected on my palmtop, and I’m twenty times the programmer Klicks is. Although he’s doubtless seen me tapping away at the keyboard, there’s no way he could have accessed the file. Still, those words, those cruel words—

Failing to act is a decision in and of itself.

Dr. Schroeder had said that to me when I talked to him about my father.

Failing to act…

“It’s not a decision I’m comfortable making,” I said at last, my head swimming.

Klicks shrugged, then settled back into the contours of his crash couch. “Life isn’t always comfortable.” He looked me straight in the eye. “I’m sorry, Brandy, but the great moral decision is up to you and me.”

“But—”

“No buts, my friend. It’s up to us.”

I was about to object again, when suddenly, 65 million years before the invention of Jehovah’s Witnesses, of Avon Ladies, of nosy neighbors, there was a knock at the door.

We know accurately only when we know little; with knowledge doubt increases.

—Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, German dramatist (1749–1832)

Klicks got up off his crash couch and made his way across the semicircular floor of the Sternberger ’s habitat to door number one. He pulled it open, walked down the short access ramp, and peered out the little glassteel insert in the main hatchway. I followed him down and looked over his shoulder. It was a big drop to the crater wall, but there, standing on it, was a dancing green troodon, hopping like a Mexican jumping bean to keep balanced on the ragged slope.

Klicks opened the outer door and looked down at the thing. “What do you want?”

The reptile was silent for half a minute. At last, it made a series of low roars like corrugated cardboard being ripped apart. Klicks turned to look at me. “I don’t think this one talks.”

I scratched my beard. “What’s it doing here, then?”

The cardboard ripping noises were growing softer, less harsh. Finally, English came from the reptile’s mouth. “Nothing, man,” it said, except it sounded more like “Nuttin’, mon.”

I had to smile. “No wonder he’s a bit slow, Klicks,” I said. “This must be the one who learned to speak from you.” I faced the troodon. “Hey, man! Day O!”

The reptile looked at the ground as if thinking. “Daylight come and me want go home,” it said at last.

I laughed.

“Your wastes are eliminated?” it said. “Your bodies cleansed?”

“Yes,” I said warily.

“Then now we shall talk.”

“All right,” I said.

“I come in?” said the troodon.

“No,” I said. “We’ll come down.”

The troodon held up a scaly hand. “Later.” In a flash, it was gone, skittering down the crater wall. I stepped to the threshold myself and looked out. It was shortly after noon. The sun, brilliantly bright against a cloudless sky, had begun to slip down toward the western horizon. Overhead I could see a trio of gorgeous copper-colored pterosaurs lazily rising and falling on columns of heated air. I took the giant first step out the door and skidded down the crater wall and onto the mud flat. Klicks, holding an elephant gun, followed behind me.

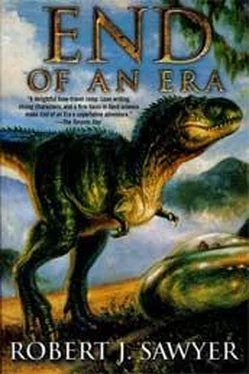

The three troodons were standing about thirty meters from the crater wall. As soon as we were both down, they moved toward us with surprising speed, long legs eating up distance rapidly. Their curved necks worked back and forth as they walked, just like pigeons, but because the dinosaurs had much longer necks, the effect was elegant instead of comical. Their stiff tails, sticking straight out from lean rumps, bounced up and down as they moved. At once, the troodons came to an instantaneous halt: no slowing down, the last stride no different from any of the previous ones. They simply stopped, cold, about three meters away from us.

The one with the diamond-shaped patch of yellow skin on its muzzle—the one that spoke like me—once again did most of the talking. “We have questions for you,” it said.

“What about?” I asked.

“Mars,” said Diamond-snout. I looked into its huge yellow eyes with their rippling irises, almost hypnotically beautiful. “I ask you again about Mars of the future.”

I shook my head, breaking away from the gaze. “And I tell you again: I’ve never been there.”

Diamond-snout seemed unconvinced. “But if you ply time, doubtless you also ply space. And even if you donut"—a one-two blink—" do not , you must have magnifying optical devices that allow you to tell much about our home.”

I looked at Klicks. He shrugged. “What you say is true, of course,” I offered. “But without knowing what Mars is like currently here in the Mesozoic, we can’t very well describe how it differs, if at all, in our time. Surely you can understand that.”

“Stop calling me Shirley,” said Diamond-snout. It used my voice; it used my jokes. “Doubtless you can give us a thumb-claw sketch of Mars without us wasting time describing its current state. Do so.”

“All right, dammit,” I said. “You might as well know, anyway.” I looked at Klicks once again, giving him a final chance to stop me if he thought I was making a huge mistake. His face was impassive. “I was telling the truth,” I said, looking back into Diamond-snout’s golden orbs. “No human being has yet been to Mars—but we’ve sent some robot explorers there. They found a lot of weird chemistry in the soil, but no life.” I looked at Diamond-snout. Its head had dipped low, the golden orbs with their vertical, cat-like pupils staring at the cracked mud. It was madness to try to interpret its expressions, to try to apply human emotions to a glob of jelly and its dinosaur marionette, and yet, to me, the thing looked shaken. “I’m terribly sorry,” I said.

“Mars dead,” said the troodon, looking up again, the reflections of the afternoon sun like little novas in its glistening eyes. “Confirm that that is your meaning.”

“I’m afraid it’s true,” I said, surprised at the emotion in my own voice. “Mars is indeed dead.” The beast’s muscles went limp as the Het within presumably tried to digest this information. My heart went out to the being. And yet, on the other hand, if a time traveler were to arrive in 2013 from 65 million years in the future, I’d fully expect him to say that my kind had passed from the face of the Earth, too. “Look,” I said softly. “It’s not so bad. We’re talking about an inconceivably long time from now.”

The troodon fixed me with a steady gaze. It reminded me of Klicks’s how-dense-can-you-be look. “As said we before, our history goes back almost double that length of time. For us, it is not inconceivably distant.” Again it dipped its long face, looking at the dried mud’s pattern of cracks and curled edges. “You speak of our extinction.”

Klicks smiled reassuringly. “All lifeforms die out eventually,” he said. “It’s the nature of things. Take the dinosaurs—”

“Klicks…”

“They’ve also been around for over a hundred million years and sometime very soon they’re going to be wiped out.”

Diamond-snout’s head snapped up. The golden eyes locked on Klicks. “What?”

It was too late to stop him. “It’s true, I’m afraid,” Klicks continued. “Earth’s ecosystem is about to change and the dinosaurs won’t be able to hack it.”

“Soon,” said Diamond-snout, the single word sounding like a hiss. “You say soon. How soon?”

Читать дальше