As the trillbright twisted its way into the distance, I knew what I would have to do. I knew I would have to change the trillbright’s name. After days of deliberation, I decided upon “slaggerbug.” Truth is truth, so I must admit the creatures actually had very little in common with insects, except size. But it was not the accuracy of the word that was important to me. With a little coaxing, “slaggerbug” became the accepted term among the colonists and scientists in the region. I correctly assumed that if I could change the word used by the local population, the rest of the galaxy would follow their lead.

Soon afterwards, I wrote an article for Galactic Science in which I coined another word—“delinction.” “Delinction” was, I proposed, the methodical elimination of a harmful or useless species. We had to acknowledge, I argued, that we no longer had life on a single planet to contend with—or even a handful of planets for that matter. We had an entire galaxy potentially teeming with life. We had to recognize that just because something “did exist,” it did not necessarily mean it “should exist.” The article, I am proud to say, was well received in this part of the galaxy.

Of course, language rarely resolves problems by itself. It is only one of many tools used to address difficult issues. And I used all my tools to help persuade others to see the logic in my argument. But it is language I am addressing here, so I will try to restrict myself to that topic.

Of course things are never as simple as they first appear. Many believe that terraforming is merely using powerful equipment to shape, reform and refine a planet. In reality, terraforming is about managing cause and effect, about judging consequences. When you are working on a planetary scale, every action will have a dramatic reaction, often one you did not predict. It is the terrologist’s job to assess those reactions and respond accordingly. Kolome is an excellent case in point.

Once the slaggerbugs were gone, the small gray plantlike organism which had sustained the colonists began to perish. It was not completely unexpected but many busicrats grew angry when what we had already identified as a possibility actually occurred.

I took, however, another approach. The organism had originally been named “calobush,” so I merely asserted that if we were going to use plant analogies, referring to the organism as a “bush” was not entirely accurate. I rationally recommended changing the organism’s name to “caloweed.” I also pointed out that although the caloweed was capable of sustaining life, much more flavorful and nutritious food could be grown on Kolome. I argued that since the caloweed was already perishing and could be replaced it would be logical to speed up the process.

Once the caloweed was gone, the remaining species declined as well. The “glushworm” and “testimite” were gone within a year. The “cessfish” hung on a little longer.

This brings us to the word “retoration.” “Retoration” would be, I asserted, simply the removal of all life from a planet in order to repopulate it with other life forms to create a more balanced ecology.

But of all the words which arose from the Kolome Project, I believe my personal favorite is “Terra-Exulta.” During the first year of the transformation, things were extremely difficult. The planet had to be temporarily abandoned while the Klarmond ships did their work. Many argued not to return to Kolome at all. I countered by saying that although things were difficult, in the end the result would be “Terra-Exulta,” a perfect world, an ideally-constructed planet.

In the end, I worked on the Kolome project for over five years. After four years, Kolome was once again a viable planet. But you should see it now. It has little resemblance to the frigid wasteland I visited long ago. The entire planet thrives, full of life and features you would quickly recognize. Even though it was one of my early works, I am especially proud of it.

Since that time I have worked on many planets, and with each project came new challenges and new words. The Walgard Project brought us anaclam, fecateria, glomoration, reimmolate, and elimitest. The Glaman Project itself spawned seventeen new nouns, six verbs and one of my favorite words, “ecoviserate.”

Oh, how I could go on, for the list is almost endless. I have, as it is, written far more than I intended. I hope you find this information useful as you continue your studies. Please let me know if you need any more information, for I do so enjoy reminiscing.

As I said at the beginning of this transmission, I will soon be returning to the old system. I am excited about once again seeing the places I left behind so very long ago. I have heard that Mars grows greener with each passing day and the Moon’s rivers run deep and clean. It warms my heart to see the positive changes my profession can make. Such works bring tears to the eyes of even the most seasoned terrologist.

But what I have heard of Earth is quite disheartening. The air is thin and the seas are thick and hot. I have also heard the population has become quite grimpting. Unfortunately, as most of our human race grows strong, there are, regrettably, some few who do not. Earth’s viability falls with each passing day and there is some talk out here of redoing it. For it is out here, among the various scattered species of the galaxy, among those new planets that we have marked with the gifts of my profession, that we have truly perfected the art of terraforming.

I have made some proposals, modest ones I assure you, for improving Earth and anxiously await a response. For is it not obvious that when a planet fails some form of dilinction is in order? Can we not see what a positive influence a retoration can have on even the most ancient of our treasured worlds? Should we not work to ecoviserate those few who are not functioning as they should and replace them with the stronger species that have grown, even flourished, out here on the fringes of civilization?

Will we not take the effort to turn the birthplace of what is now a well-traveled species—a galactic species—into a true Terra-Exulta?

I have already taken the liberty of ordering eight Klarmond ships to head toward Earth. It will be my gift to humanity—using those talents I have developed out here, so very far from Sol—to turn our ancestral home into the Terra-Exulta it deserves to be. What a wonderful opportunity. Who knows what new words will spring from this new project?

Give my love to the family.

Humbly Yours,

Harald K. Jeribob

Terrologist

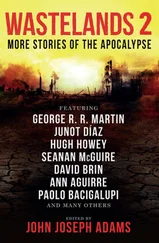

AFTERMATHS

by Lois McMaster Bujold

Lois McMaster Bujold is a five-time winner of the Hugo Award and the winner of three Nebula Awards. She has published nearly two dozen novels, including several in her popular Barrayar series, which mostly feature aristocrat and interstellar spy Miles Vorkosigan. The first of these, The Warrior’s Apprentice , appeared in 1986, but she made her debut a few years earlier in 1984 when she sold a short story to Twilight Zone Magazine . Over the years, she hasn’t written much other short fiction, so this one is a rare treat.

Although Bujold’s career started off in science fiction, lately, she’s turned her hand to fantasy, writing first the Chalion series, then moving onto The Sharing Knife; volume four of that series, Horizon , came out in February. Learn more about her and her work at www.dendarii.com.

This story, which takes place in her Barrayar milieu, takes a rather grim look at some of the professions that will arise in the wake of interstellar war.

The shattered ship hung in space, a black bulk in the darkness. It still turned, imperceptibly slowly; one edge eclipsed and swallowed the bright point of a star. The lights of the salvage crew arced over the skeleton. Ants, ripping up a dead moth, Ferrell thought. Scavengers…

Читать дальше