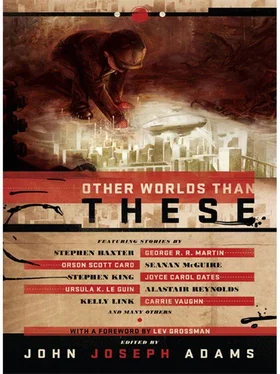

OTHER WORLDS THAN THESE

Stories of Parallel Worlds

edited by John Joseph Adams

“Go then, there are other worlds than these.”

–Jake Chambers, to Roland Deschain of Gilead [from

The Gunslinger by Stephen King]

When I read The Chronicles of Narnia as a child, it didn’t so much introduce me to the idea that there was another world as confirm my already grave suspicions on the subject. Even at the tender age of eight I was—as I suspect you were, and are, if you’re reading this book—one of reality’s natural critics. Oh, I knew that the real world had its good points. One must be charitable after all. Candy, for example, and cats, and hot baths. But by and large the material was just a bit thin. The jokes weren’t funny, the catering was uneven, and the less said about one’s fellow players the better. I had a powerful urge to see what was on in the next theater over.

Until I read The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe —and Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and The Phantom Tollbooth, and The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, and The Chronicles of Amber—I thought I was the only one who felt that way. Of course this can’t be all there is: this ludicrous excuse for a universe can only be a rough draft, a temporary substitute, the amateur opening act before the main event, which will be more magical, more exciting, more meaningful, more ecologically sound and otherwise superior in every way.

This wasn’t actually the point of any of those books, of course. That fact was lost on me then, but it isn’t now. Now I understand that the children in the Narnia books went to another world in order to imbibe crucial life lessons at the paws of the lion-god Aslan. Then when they were deported back to England at the end of the book they could experience reality, such as it was, with a renewed appreciation, and they could spread the Word of Jesuslan to the unenlightened.

That would have been the “correct” lesson to draw from The Chronicles of Narnia, but if any child has ever read those books correctly I will eat my hat. When he wrote them Lewis unwittingly let loose a monster of an idea, one even more powerful than the idea he was actually trying to put across. The lesson you receive from The Chronicles of Narnia is that reality is not where it’s at, my friend, so get out by any point of egress you can find and get into somewhere better.

Of course, Lewis didn’t invent that idea. It’s an old fantasy, far older than Narnia—far older, I suspect, than Christianity. The idea that you can enter another world, generally heaven or some heaven-analog, without having to die first exists in any number of religions; it is technically known as ascension, or assumption, or (my personal favorite) translation. The Virgin Mary managed it, as did Elijah, and for that matter Bilbo and Frodo Baggins. It was given new life in the twentieth century, and a new spin, pun intended, by the so-called many-worlds interpretation of quantum theory, which posits the idea that all possible universes are in fact real, and the multiple possible outcomes of every event spawn multiple universes in which each of those outcomes is realized. Schrödinger’s cat is dead in one, and alive and purring in another. This theory is actually taken seriously by quite a few non-insane physicists.

Far more compelling would be a very-many-worlds hypothesis, in which all universes exist, both the possible and the impossible, but unfortunately no one sane believes that, not even an old traveler in the realms of gold like me. Fortunately there is a device, entirely real, which can take you into those other realities. Not permanently, but for short, ecstatic flights that are very much worth taking. You’re lucky enough to be holding one such device in your hands right now. As Aslan would say: further up and further in.

INTRODUCTION

JOHN JOSEPH ADAMS

What if you could not only travel any location in the world, but to any possible world? That is the central conceit of this anthology. Or, to be more precise, it aims to collect the best stories that fall into one of two categories: parallel worlds stories or portal fantasies.

A portal fantasy is a story in which a person from one world (usually the “real” world) is transported to some Other World (via some magical or unexplained means), usually one full of impossibilities and generally much stranger than the one they come from.

A parallel worlds story is one in which a person from one world (usually the “real” world) is transported to some Other World (via some scientific/technological means), usually a parallel universe/alternate reality either just slightly different than the one they left, or else vastly different, with different physical laws, but strictly scientifically plausible.

As you can see from the parallels in those two descriptions, the portal fantasy and the parallel worlds story are essentially two sides of the same coin; heads, you get fantasy, tails you get science fiction, but in each the characters’ journey is essentially the same: to explore and wonder at these strange Other Worlds…or to do their damnedest to get back home.

When I first set out to assemble this anthology, I had been thinking primarily of parallel worlds fiction, until the above realization occurred to me. Once it did, I knew that if I were to consider one side of the coin I had to also consider the other, and at that point the entire anthology clicked into place.

(Accordingly, it felt to me like the two types of story should be in dialogue with each other in the context of the anthology, so I did not separate them in the table of contents; instead, both types of story are mixed together throughout the book. It should also be noted that I shied away from including any stories that are primarily based on time travel—as time travel stories are their own genre, though of course time travel does, in essence, create parallel worlds.)

The tropes of Other Worlds fiction have fired the imaginations of millions of readers over the years. The portal fantasy has the earliest roots, with prominent early examples including The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland , and The Chronicles of Narnia. The tradition has continued, with modern day writers picking up the torch, such as Stephen King (The Dark Tower), Philip Pullman (His Dark Materials), and Lev Grossman ( The Magicians ).

Although one might assume that parallel worlds stories are of a more recent vintage, the hypothetical idea of multiple universes has actually been around since the late nineteenth century, and, indeed, some early examples of parallel worlds fiction can be found in the works of science fiction’s most prominent early practitioner, H. G. Wells. (However, it is fair to say that the majority of this type of story has been written after the many-worlds interpretation theory of quantum mechanics was first postulated and popularized in the late ’50s.) For parallel worlds stories, there are fewer obvious classics to reference, but there are The Gods Themselves by Isaac Asimov, The Female Man by Joanna Russ, and The Big Time by Fritz Leiber, with recent examples including The Neanderthal Parallax trilogy by Robert J. Sawyer, The Mirage by Matt Ruff, and Alastair Reynolds’s Absolution Gap .

(For more Other Worlds novel-length works, see the “For Further Reading” appendix located at the end of this anthology.)

So let’s take a trip through the looking glass… or into the universe next door. Thirty different Other Worlds await you; to visit the first, simply turn the page…

Читать дальше