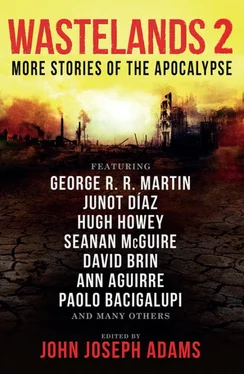

WASTELANDS 2

More Stories of the Apocalypse

Edited by John Joseph Adams

INTRODUCTION

JOHN JOSEPH ADAMS

It’s hard to imagine following up something like the end of the world.

But fans of post-apocalyptic fiction know that end-of-the-world stories aren’t really about the end —they’re about new beginnings and the end of the world as we know it . Our stories, our lives, our world continues on, even if the trappings change and the facade of civilization falls by the wayside. As the title of George R. Stewart’s masterpiece reminds us: the Earth abides.

And as the Earth abides, so does our interest in post-apocalyptic fiction. The genre has continued to flourish in the years since the original Wastelands (hereinafter referred to as “Volume One”) was published, and when I began reading for the new anthology I discovered a wealth of material to choose from. Yet it was very difficult to even contemplate following up a book like Volume One, which, to my astonishment, was widely hailed as not only the definitive post-apocalyptic anthology but as one of the finest anthologies of any kind . And, although it was my first anthology, it contained works by the likes of Stephen King, George R. R. Martin, Orson Scott Card, Octavia E. Butler, and other legendary figures of the SF/fantasy field. When you come out of the gates with that kind of success, it’s daunting to say the least to contemplate a follow-up.

But my love for post-apocalyptic fiction has not waned since editing Volume One, and it’s clear the genre is still at the forefront of many authors’ minds as well. Five of the stories included here are from the 20th Century, but the remaining twenty-five were all published from the year 2000 onward, and eighteen of those were originally published in the years since Volume One came out. That seems to indicate that the boom in post-apocalyptic fiction that I detected back when I decided to put Volume One together is still ongoing, and writers and readers now are seemingly as fascinated with the apocalypse as we were back in the genre’s heyday in the 1950s. Or, in other words, it’s certainly not the end of the world for the end-of-the-world genre.

In Volume One’s introduction (which you can find online at johnjosephadams.com/wastelands), I traced the rise and resurgence of post-apocalyptic fiction, citing the dawn of the Atomic Age as the former, and 9/11 as the latter. I also speculated at length about why we’re so fascinated by the end of the world. There, I said, “To me, the appeal is obvious: it fulfills our taste for adventure, the thrill of discovery, the desire for a new frontier. It also allows us to start over from scratch, to wipe the slate clean and see what the world may have been like if we had known then what we know now.” But it’s since occurred to me that many of us have a strong attraction to things that scare us; there wouldn’t be a horror genre otherwise. And in many ways, post-apocalyptic fiction is the scariest kind of fiction there is, because the more plausible a horrific story is, the scarier it is. Stories about demons and supernatural monsters can be entertaining, but deep down I don’t find them particularly scary, because I’m pretty certain those things don’t—and never will—exist.

The end of the world, however? That could happen.

Will we ever sate our appetite for stories about the end? It’s hard to imagine that we will. At least not until the end actually comes…

THE TAMARISK HUNTER

PAOLO BACIGALUPI

A big tamarisk can suck 73,000 gallons of river water a year. For $2.88 a day, plus water bounty, Lolo rips tamarisk all winter long.

Ten years ago, it was a good living. Back then, tamarisk shouldered up against every riverbank in the Colorado River Basin, along with cottonwoods, Russian olives, and elms. Ten years ago, towns like Grand Junction and Moab thought they could still squeeze life from a river.

Lolo stands on the edge of a canyon, Maggie the camel his only companion. He stares down into the deeps. It’s an hour’s scramble to the bottom. He ties Maggie to a juniper and starts down, boot-skiing a gully. A few blades of green grass sprout neon around him, piercing juniper-tagged snow clods. In the late winter, there is just a beginning surge of water down in the deeps; the ice is off the river edges. Up high, the mountains still wear their ragged snow mantles. Lolo smears through mud and hits a channel of scree, sliding and scattering rocks. His jugs of tamarisk poison gurgle and slosh on his back. His shovel and rockbar snag on occasional junipers as he skids by. It will be a long hike out. But then, that’s what makes this patch so perfect. It’s a long way down, and the riverbanks are largely hidden.

It’s a living; where other people have dried out and blown away, he has remained: a tamarisk hunter, a water tick, a stubborn bit of weed. Everyone else has been blown off the land as surely as dandelion seeds, set free to fly south or east, or most of all north where watersheds sometimes still run deep and where even if there are no more lush ferns or deep cold fish runs, at least there is still water for people.

Eventually, Lolo reaches the canyon bottom. Down in the cold shadows, his breath steams.

He pulls out a digital camera and starts shooting his proof. The Bureau of Reclamation has gotten uptight about proof. They want different angles on the offending tamarisk, they want each one photographed before and after, the whole process documented, GPS’d, and uploaded directly by the camera. They want it done on-site. And then they still sometimes come out to spot check before they calibrate his headgate for water bounty.

But all their due diligence can’t protect them from the likes of Lolo. Lolo has found the secret to eternal life as a tamarisk hunter. Unknown to the Interior Department and its BuRec subsidiary, he has been seeding new patches of tamarisk, encouraging vigorous brushy groves in previously cleared areas. He has hauled and planted healthy root balls up and down the river system in strategically hidden and inaccessible corridors, all in a bid for security against the swarms of other tamarisk hunters that scour these same tributaries. Lolo is crafty. Stands like this one, a quarter-mile long and thick with salt-laden tamarisk, are his insurance policy.

Documentation finished, he unstraps a folding saw, along with his rockbar and shovel, and sets his poison jugs on the dead salt bank. He starts cutting, slicing into the roots of the tamarisk, pausing every thirty seconds to spread Garlon 4 on the cuts, poisoning the tamarisk wounds faster than they can heal. But some of the best tamarisk, the most vigorous, he uproots and sets aside, for later use.

$2.88 a day, plus water bounty.

* * *

It takes Maggie’s rolling bleating camel stride a week to make it back to Lolo’s homestead. They follow the river, occasionally climbing above it onto cold mesas or wandering off into the open desert in a bid to avoid the skeleton sprawl of emptied towns. Guardie choppers buzz up and down the river like swarms of angry yellowjackets, hunting for porto-pumpers and wildcat diversions. They rush overhead in a wash of beaten air and gleaming National Guard logos. Lolo remembers a time when the guardies traded potshots with people down on the riverbanks, tracer-fire and machine-gun chatter echoing in the canyons. He remembers the glorious hiss and arc of a Stinger missile as it flashed across red-rock desert and blue sky and burned a chopper where it hovered.

Читать дальше