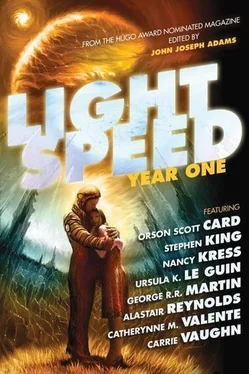

John Adams - Lightspeed - Year One

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Adams - Lightspeed - Year One» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Prime Books, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Lightspeed: Year One

- Автор:

- Издательство:Prime Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:978-1607013044

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Lightspeed: Year One: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Lightspeed: Year One»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

www.lightspeedmagazine.com

Lightspeed: Year One — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Lightspeed: Year One», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“The next thing you’ll be telling us, Martin,” Dunlapil said as if to forestall a discourse on galactic comparisons, “is that these plants are the aliens who built these cities.” He shot me a grin.

“That ought to be obvious,” Chavez said with such a lack of rancor that the disbelief I had been entertaining disappeared. “Commissioner”—Chavez’s grave eyes met mine—”can you give me another reason why every city has similarly fenced lots, all placed to catch full daily sun? Why the velvet fields with that central dominant Tree symbol appear to be the reverent focus of the aliens—excuse me—the indigenous species?”

“But they’re humanoid,” Dunlapil said in protest.

“Their culture is agrarian. And there are no grazers. Not a single example of that blasted Tree anywhere on the planet—yet!”

That was when I truly began to be afraid.

“There are no grazing beasts,” Chavez went on inexorably, “because they have been eliminated to protect the velvet fields and whatever is growing in them now.”

“You mean, when those fields bloom with whatever it is they bloom with, the aliens will return?” Dunlapil asked.

Chavez nodded. “If we haven’t irreparably altered the growth cycle.”

“But that’s fantastic! An entire civilization can’t be dependent on a crazy who-knows-how-long cycle of plant life.” Dunlapil was sputtering with indignation.

“Nothing is impossible,” replied Chavez at his most didactic.

“Your research has been sufficiently comprehensive?” I asked him, although I was sick with the sense of impending disaster.

“As comprehensive as my limited equipment and xenobotanical experience allow. I would welcome a chance to submit my findings to a board of specialists with greater experience in esoteric plant-life forms. And I respectfully request that you have Colonial Central send us a team at once. I’m afraid that we’ve already done incalculable damage to the—” He paused and, with a grim smile, corrected himself. “— indigenous organism seeded in those fields.”

The semantic nicety jarred me. If Chavez was even remotely correct, we would require not only xenobotanists and xenobiologists but an entire investigation team from Worlds Federated to examine our intrusion into a domain that had not, after all, been abandoned by its occupants like a Marie Celeste but had simply been lying fallow—with the indigenous natives quiescently in residence.

As Chavez, Dunlapil, and I walked from my office toward the Comtower, I remember now that I felt a little foolish and very scared, like a child reluctant to report an accident to his parents but dutifully conscientious about admitting his misdemeanor. The plastisteel tower had never looked so out of place, so alien, so sacrilegious as it did now.

“Hey, wait a minute, you two,” Dulapil protested. “You know what an investigation team means… ”

“Anything and everything must be done to mitigate our offense as soon as possible,” Chavez said, interrupting nervously.

“Dammit!” Dunlapil stopped in his tracks. “We’ve done nothing wrong.”

“Indeed we have. We may have crippled an entire generation.” Chavez spoke with an expression of ineffable sorrow.

“There are plenty of fields we never touched. The aliens—natives—can use them for food.”

Chavez’s sad smile deepened and he gently removed Dunlapil’s hand from his arm. “‘From dust ye came, to dust ye shall return, and from dust shall ye spring again.’“

It was then that Dunlapil understood the enormity of our crime.

“You mean, the plants are the people?”

“What else have I been saying? They are born from the Trees.”

We did what we could even as we waited for the specialists and investigation team to arrive.

First we cleared the animals and crops from every one of the velvet fields. We removed every sign of our colonial occupation from the cities. The team, composed of five nonhuman and three humanoid species, arrived with menacing expedition well before the initial flood of xenospecialists. The team members did not comment on our preliminary efforts to repair our error, nor did they protest their quarters in the hastily erected dwellings on the bare, dusty plain and the subsequent roaring activity of the spaceport close by. All they did was observe with portentous intensity.

Of course, except for vacating the cities—and occupying them was apparently the least of our cumulative crimes—everything we did to remedy our trespass proved horribly inept in the final analysis. We would have been less destructive had we kept the cattle on the velvet fields and not slaughtered them for food. We ought to have let the crops ripen, die, and return to the special soils that had nourished them. For the fields we stripped produced the worst horrors. But how were we to know?

Now, of course, we know all too fully. We are burdened to this very day with guilt and remorse for the wholesale dismemberment and dispersal of those irretrievable beings; eaten, digested, defecated upon by grazers. And again, eaten, digested, and eliminated by those who partook of the grazers’ flesh. Of the countless disintegrated natives removed from their home soil by unwitting carriers, none can bear fruit on foreign soil. And on their own soil, to repeat, the fields we had stripped produced the worst horrors…

I remember when the last report had been turned in to the eight judges composing the investigation team. Its members wasted no further time in formulating their decree. I was called to their conference room to hear the verdict. As I entered, I saw the judges seated on a raised platform, several feet above my head. That in itself was warning that we had lost all status in Worlds Federated.

A flick of the wrist attracted my attention to one of three humans on the team. Humbly I craned my head back, but he refused to glance down at me.

“The investigation is complete,” he said in an emotionless tone. “You have committed the worst act of genocide yet to be recorded in all galactic history.”

“Sir…” My protest was cut off by a second, peremptory gesture.

“Xenobiologists report that the growths in the velvet fields have reached the third stage in their evolution. The parallel between this life-form in its second stage and that of the cellulose fauna of Brandon Two is inescapable.” Chavez had already told me of that parallel. “Now the plants resemble the exorhizomorphs of Planariae Five and it is inevitable that this third stage will give way to the sentient life pictured in the murals of their cities.

“You came here as agrarians and agrarians you shall be, in the fields of those you have mutilated. What final reparations will be levied against you, one and all, cannot be known until the victims of your crimes pronounce the penance whereby you may redeem your species in the eyes of the Worlds Federated.”

He stopped speaking and waved me away. I withdrew to announce the verdict to my dazed fellow colonists. I would far rather that we had been summarily executed then and there, instead of being worn and torn apart by bits and pieces. But that was not the way of judgment for those who trespass in modern enlightened times.

We could not even make an appeal on the grounds that the planet had been released to us, for the colony in its charter took on all responsibility for its subsequent actions, having reaped benefits now so dearly to be paid for.

So we worked from that day until Budding Time late that heinous fall. We watched anxiously as the seedling exorhizomorphs grew at a phenomenal rate until they were ten, then twenty, finally twenty-five feet high, thick-trunked, branching out, lush with green triangular foliage. By midsummer we knew why it was that during our time on the planet we had never been able to find any examples of the Tree: Such Trees grew once every hundred years. For they were the Trees of Life and bore the Fruit of Zobranoirundisi in the cellular wombs, two to a branch, three to eleven branches per Tree. In the good fields—that is, the unviolated fields.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Lightspeed: Year One»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Lightspeed: Year One» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Lightspeed: Year One» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.