Of course, nothing kills you right away, and the same can be said for meteors. They don’t have to kill you right away. This was the case in the rocket Maxon was sitting in, headed for the moon. It did not kill them right away. Yet they all four knew, and all the other humans back on Earth who were paying attention knew, that in that moment, the mission changed, and there was very little hope of a happy reunion. In the mad spinning mechanism, the cruel randomness of space, with its dire temperature shifts, its spinning infernos, its ferocious pellets, the chance of a human surviving was very small. The fact that most astronauts came back and were fine was a testament to just how tiny the steps taken by humans into space had been.

So the little room got littler. The astronauts began to sweat. The air became tainted, as if they could taste the chemicals. Their feet longed for the bumpy heaviness of Earth. Their lungs yearned for the sweet, pure air of Manhattan, or even a coal mine, air that was made the real way, by plants and other people and cars and breezes and animals, not manufactured and tanked. Now they were not only cramped inside a spaceship, they were cramped inside a damaged spaceship. The panic was there at the back of their throats, with the desire to claw their way out, escape, restart, make different life choices.

Gompers took control, barking orders and asking for status reports. Fred Phillips, so obnoxious on his downtime, became a mechanism of assessment, snapping out clipped answers and clicking away on a board of buttons and levers. Maxon could do nothing. His limbs went still. His worry was distant. He thought of Sunny sitting in a room at NASA in Langley, looking at an uplink to the rocket’s control room. She would see their four shining heads, round and hairless, closed to the elements. Would she think he looked bald? Would she think he looked familiar? Would the boy be there, in his helmet? Would Sunny be aware they were all encased in their own skulls? Maxon closed his eyes. Robots were more suited for this. Robots were more equipped. There was nothing a robot would regret, faced with its destruction in the aftermath of a meteor strike.

This is the story of an astronaut who was lost in space, and the wife he left behind. Or this is the story of a brave man who survived the wreck of the first rocket sent into space with the intent to colonize the moon. This is the story of the human race, who pushed one crazy little splinter of metal and a few pulsing cells up into the vast dark reaches of the universe, in the hope that the splinter would hit something and stick, and that the little pulsing cells could somehow survive. This is the story of a bulge, a bud, the way the human race tried to subdivide, the bud it formed out into the universe, and what happened to that bud, and what happened to the Earth, too, the mother Earth, after the bud was burst.

If Sunny were here, he would say, “Don’t be afraid. Think of the meteor as a giant meatball. One I will eat and gain twenty pounds.” She was always saying he was too skinny.

The saddest thing that anyone has ever seen is an oil town that is no longer booming.

In 1859, crude oil was discovered in fat pockets under the foothills of the Appalachians in western Pennsylvania, in Yates County. Forward-thinking people stuck pipes down into the ground and began sucking out this oil as fast as possible, pouring it into barrels, and shipping it around. They were able to sell it for quite a fine profit. They organized themselves into boroughs and towns and even cities. They built monstrous, huge Victorian houses, lit them with strange and dangerous wiring, and perched them onto the sides of small mountains. Down at the bottom of the mountains the Allegheny River cut through. Time passed and as the oil came up out of the ground with less determination, they moved the pipes around, and switched to coal. They mined for coal under the ground and then strip-mined the top of the ground and then turned to lumber.

Meanwhile in nearby Crowder County, they couldn’t find any oil. Whatever the reason, the Crowder County residents had to dig in and rely on agriculture to get them through the turn of the century. By the time the oil had run dry in Yates County, the farmers of Crowder County had scraped down the hillsides and layered fields of corn, soybeans, soup beans, all up and down. They were rich farms, sweet farms, mooing and rustling farms. They were farms solvent with non-oil money. And so when Pennzoil moved down South to become Texazoil, and the health and welfare of the citizens of Yates County came acutely into question, the farmers of Crowder County sat in stoic victory on their well-oiled threshers, pounding out their prosperity.

But the barons of oil in Yates County were still rich. When they had gutted, disemboweled, razed, and plucked the land around them, they turned in on themselves in their Victorian homes, and when the money ran out, in approximately 1952, they mostly died. Now the people who had serviced all the barons of oil and coal and lumber still remained in the oil towns, and with the lords and ladies gone they took over the unwieldy Victorian houses and dealt with the inconvenient kitchen layouts and installed refrigerators in unlikely places and laid down cement in the basements and managed not to burn down the whole city.

Everyone needs groceries and a place to buy tires, so the tire-store guy can sell to the grocer and vice versa. Every year there is a slightly smaller GNP for the decaying oil town with no more oil in it. Gradually the houses fell into disrepair. Gradually everything slowed down. While the farmers in Crowder County sat smug on their silos of grain, the remnant in Yates County roosted in the finery of days past, and the ground watered by wealth, prestige, and privilege brought forth a curiously high percentage of geniuses. Maybe it was a result of the bizarrely grandiose public establishments, gifts of dead oil magnates. What rural public high school has a planetarium? The school in Yates County, where Sunny and Maxon had their education, was different in a number of ways. A commitment to high-tech updates was one, funded by long-dead benefactors. Its high concentration of statistical geniuses was another. The causal relationship between these two anomalies was uncertain.

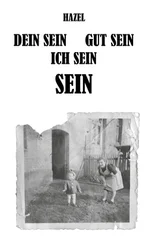

In any case, this was where Sunny and Maxon grew up among those brought shockingly low, and those random scatterings of monstrous intellects. From the Amish farms, from the trailer parks, from the rotted old estates with broken windows and railings they sprouted up, shooting through the local schools with such powerful force they were shot out, far out into the world, and landed as chiefs of surgery in Chicago, research scientists in LA, sociologists in Denver. Maxon was not the first to rise up from such oily, strange beginnings to win a Nobel Prize. They were a rare breed, fed on the scraps of the oil wealth, nurtured in the overprivileged schools, always with the urgent aim of escape from the decaying place of their birth.

In the moment of impact, where the stars fell on him, Maxon remembered a day in the high-school planetarium, and the way Sunny’s head had looked, in the center of that planetarium. She was sitting so upright in a chair, and looking so bald, like a cartoon of an idea. Aha! A lightbulb, her neck the part you screw in, her skull the glass bulb, her brain, her soul, her generosity the filament. Sitting there in the dark, in the light of the thousand stars, shot up by his lamp, he, the bold projectionist, illuminated the stars. What a way to pick up women.

* * *

HE WENT TO HIGH school first. By the time Sunny got there, he was a sophomore. There were kids there from around the county, mostly kids known to Maxon but some not. He went scowling through his first year there without her. He made enemies. He scorned teachers. He put people in their place. He sneered at their unread, unresearched, lazy intellects. The mother had tried to train him in all the ways he needed to behave in school. In elementary school, this was a success. To keep him from running in the hallways, she said, “Maxon, your rate of speed is independent of your lack of obstacles. Just because you can run fast doesn’t mean you should.” Later, he wrote down the math:

Читать дальше