He looked at his watch. What did time mean, en route to the moon? What did the rotation of the Earth mean, apart from a navigational consideration, apart from the physics? What did it mean, to the cycling consciousness of the human body, that the Earth had rotated, somewhere far away, without his feet on it, without his body, prone, asleep on it, stretching over the bottom of any bed he’d ever lain in, his feet always spilling out, his head always butting against the wall.

For a man so long, restraint was essential. He was always bumping into things. Maxon’s fuse was long, too, his temper even longer than his legs. There had been times when his limit had been breached, and his ability to tolerate the little clinks and rattles when his limbs bumped into knickknacks was the first thing to go. In the house where he grew up, for example, there were so many things. So many piles, shelves stacked high with papers, jars, shoeboxes, empty cans, lumps of fishing tackle, scraps of leather, and the filth and detritus of a house full of boys. So in their house Sunny and Maxon didn’t keep decorations on the surfaces. They were smooth and clean, a candle here and a bouquet of eucalyptus there, brutally arranged by Maxon for minimal clutter, just enough to keep them looking like they lived in a proper home. When they were first married, Sunny didn’t care. She had no feelings about what things should be on counters or tables. It didn’t matter to her.

When they moved to Virginia she started making changes in the arrangements, asked that he rotate them by seasons. She had bought an antique clock, put it not equidistant between two candles. There were other purchases, and contractors coming in to work. He knew that this was the time she started caring about the house. This was the time she became different, when they moved to Virginia so he could have the lab at Langley. When they, together, made the boy.

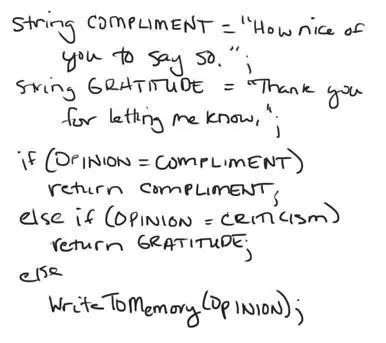

He had written in his notebook during the night. He looked down and saw that he had written the words “Sunny’s great disappointments:” and then underneath he had made three strong bullets. Beside the first was “Me” and then “My behavior.” Then finally, “My genetic material.” He saw the words “Sunny said:” and then three more bullets underneath. He wrote “Why can’t you just be a normal fucking human being?” and “It is all your fault that Bubber is how he is” and “I hate my mother for being right, but she was right. She was right!”

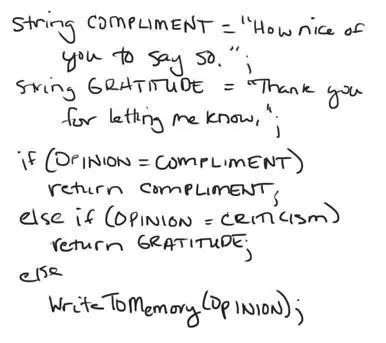

Maxon knew that elsewhere in his notebook was a page that said this:

“Thank you for letting me know,” he said to Sunny’s words. And without any further hesitation, he turned the page, smoothed out the fresh sheet, and began the day of work. He considered the mother, her smooth golden head, her dour pronouncements, her long illness, but then he tried to put the image right out of his head.

* * *

SHE DROVE TO THE YMCA and put Bubber into his swim trunks, because this is what they did after preschool on Tuesdays and Thursdays. Bubber’s schedule was sacred, like a litany, helping him fit into the world. He danced from foot to foot in the changing room, his hand on the door, waiting for her to come along. The pool had an L shape, shallow in the bottom part and deep on the long part for laps. Bubber’s goggles were bright green and his trunks had bugs all over them, red and yellow. When she came along, finally, he flopped into the pool without looking back at her, without noticing, immediately engaged in his own world. Sunny could smell the chlorine, see the rust around the drains, and there was a crippled man in the hot tub, his face pinched and persevering. She had looked into the wide mirrors of the YMCA changing room. Under the fluorescent light her head looked pointier, more gray.

She stood in her skirted maternity bathing suit on the wheelchair ramp that wound down into the pool. Her giant belly pressed against the railing. This is where she always stood. The YMCA rule said a parent had to stay within arm’s length from a child this small. So, there she was. Bubber was a freakishly good swimmer, and he always had been. He had never been afraid, even for a moment, of drowning. In fact, when he was even smaller, he’d walked right off the side of the pool, scaring everyone. Eventually he’d worked out swimming, and now he was an expert. There was never any stimming in the water. Never any banging or shrieking. So they came here twice a week.

Normally, with her wig on, she stood on the ramp, not putting her head in the water. Today, if she wanted to, she could go all the way down, down to the bottom of the pool. She tilted her white head down to look at Bubber. He had a small plastic frog. The frog was jumping on and off a small swim float, assisted by Bubber. There were noises to go with the jumps, something that sounded like rewinding a tape. It jumped on and off many, many times. It looked like he would never get tired of playing with the frog. Sunny’s skin was cold because she was standing under one of the giant vents in the air-circulating pipes. Her head was very cold. In fact, she froze.

Maybe, without a wig, she was a mother who would plunge into the water, feeling it rush warm and cool around her, holding her up. Or maybe at this point in her motherhood, at this advanced state of habitual wig-wearing, Sunny had written onto her flesh the true purpose of her life at that moment, which was just to shut up and watch over the child. The child enjoyed the water, and Sunny only had to stand here and make sure he didn’t die. This was her default position. She stood in the mommy body in the mommy spot. All she had to do, at that recurring moment from about one o’clock until about two o’clock on Tuesday and Thursday, was to tend the child. Did she have to be comfortable at this time? No. Did she have to enjoy the water? No. There were many times in her life when she had been comfortable and had enjoyed water. Now was a time when she was protecting her child and promoted his happiness as the pool enriched his life and developed his mind and body. So why cloud that with her comfort or discomfort? Wig or no wig. This is what she told herself, to prevent herself falling into the water, going deep down, playing with her own feet, looking at the lights.

She was reminded of a time in her life before anyone had looked at her to consider if she would make a great wife and mother. Then it had been lots of fun on the beach. She glided along the hot sand in a string bikini, walking as if she’d invented legs, head greased with coconut oil, floppy hat dangling from one hand. She swam like a dolphin, no swim cap, no tangle of hair around her goggles. Those were good times, but who really cares? There are people walking around with no limbs, or whose children have fallen out of buildings and died, or people who can’t come to the YMCA because they live in some godforsaken rural hellhole. She never knew, before she had a child, the concern she would feel for him. She felt real actual concern.

Sunny had taken swimming lessons as a child. Her mother believed every child should learn to swim, ride a horse, and play the piano. What had occupied her mother’s mind during those long lesson hours? When Sunny had been straining to tread water for three minutes, getting her skinny ass hollered at by the big high-school swimming coach. Was her mother sitting there? She couldn’t remember. Thinking about her? Comparing her, to her extreme disadvantage, to the other swimmers? Maybe her mother was thinking, That’s my daughter. The bald one . Emma had been a diver. Had spoken French. Had graduated at the top of her class. Sunny had been a lazy swimmer, prone to spells of floating and underwater drifting. She had spoken very poor German, had majored in something her mother found incomprehensible.

Читать дальше