All but the last page. When it was found, that page was still wet, and on it were four words, looking as if they’d been written quickly, with a muddy finger, perhaps in justification. They said: “I did knock first.”

About “Who Knocks?”

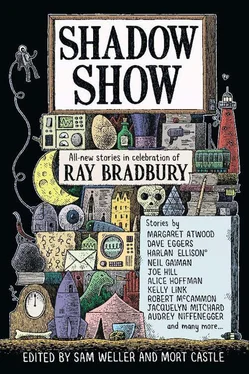

I was introduced to Ray Bradbury in grade school, when we read “A Sound of Thunder,” and the experience was powerful, knowing that he’d grown up in Waukegan, a few towns away from where I was raised. And every year or so thereafter, we were assigned one or another Bradbury text, and always I was floored by his boundless imagination. I have to admit, though, that I hadn’t read him in many years until a few years ago, when I picked up an old edition of an anthology edited by Alfred Hitchcock called Stories Not for the Nervous . In it was a Bradbury story about time travel, crime, marriage, and film, all set in the 1930s in Mexico—a lot to cover in a ten-page story. But Bradbury pulled it off, brilliantly, and my respect for his body of work—the breadth and scope of which is stunning—was renewed.

—Dave Eggers

RESERVATION 2020

Bayo Ojikutu

Daily, Joseph descended the stairwell, then walked along the ground-floor path aside his housing unit. He’d slip coins into a red machine at corridor’s end to buy a can of Coca-Cola—and so he’d continue to believe that the old America was nearby. No matter the ninnies’ chants, nor what he did not see along the way to that symbol of vending democracy. No flags whipped in mountain wind, nor stone totem temples to founders and settlers, nor upright souls traipsing along paved gold—yet Coca-Cola remained the Chief Bottler of Empire, never to slough off into the abyss. Joseph tasted the nectar slowly, let bubbles sting along his lip and throat, and felt the bite at what remained of his kidneys, and he knew. That pang, according to the fathers who’d settled their compound, was the magic elixir of treasure snatched up from dirt, hands raking through the bounty, suicide left as the aftertaste of plunder, masked by syrup and sugar and coca dope. The soul that sipped, for spare silver coin—that soul swallowed all that was to be had from the living earth, God bless it.

Now when those options were taken, and the compound’s admin replaced Coke machines with a new set of off-brand selections for sale—or perhaps Royal Crown blue (did RC exist still? Perhaps in the Old World?)—while still demanding the same coin for the purchase, then he would listen to the rabble-rousing youths who blocked the square’s streets each rush hour. And he might accept then that all that was good in the life of liberty was kept from them.

“They caught Chevy yet?”

There was nothing to be had in pretending the question went unheard. “Not that I know.”

“Haven’t heard from him yourself neither?” Joseph looked at the peach-skinned bit of androgyny perched beneath his elbow as he lowered the Coke can. Hair whipped all about the youth’s shoulders; earrings poked both earlobes; another joined his nostrils together while dirty silver jutted from his upper bicuspid; eyeliner decorated the blink in doughy eyes. He carried a maroon-and-pink-checkered skateboard beneath his stubby left arm. Hadn’t the settlers come to their compound to eradicate, or at least escape, such living confusion among the young? Joseph brought the beverage back to his mouth.

“Truthfully,” the boyish teen purred. “You can trust me. I’m not with them.”

“Mmmh, ‘them.’ Surely.” Joseph stepped away as he mocked, although he recognized the teen as one of his son’s young clamoring followers from the neighboring downstairs units.

“For sure,” the boy begged. “I heard them chanting Chevy’s name today in the square, after school. On my way—”

“Yeah? You made it to school today dressed like that?”

“Of course, sir, I did.” He hopped and pumped a fist as if protesting in the center himself. “ Chevy! Chevy! Viva Chevy! Viva la libertad! All afternoon, just like that.”

Carbonation bit Joseph’s innards as it passed along, and the soda shivered his empty gut. “In Foreigner, hey? That’s how they said it in the square? What does that mean, even?” He crinkled the Coke can’s rim, his taste finished.

The boy dropped his skateboard to the white stone path and scooted at Joseph’s side as they headed from the machine, west toward the center square. “Not sure,” he said. Lying, most likely, Joseph guessed. “Sounds like ‘life and liberty.’ For your son. Like he’s a hero—”

“But you’re not with them?” He did not intend for the boy to answer.

“I’m not with them who’s lying about Chevy, trying to mark us with criminal insult on the fortieth anniversary. Not them, sir. I’m with the people.”

“Demo,” Joseph said, repeating the strange word Chevy had used for the rabble-rousers of his class before leaving the compound’s walls.

“Yes, sir,” the boy agreed, two words blown in skateboard wind. “Demo crazy. That’s us.”

Joseph squinted to read the sideways words scribbled along the black cotton of the boy’s T-shirt, neck to hem, as he rolled along: IN THIS DARK PIT, ALONE, YOU ARE LOST. BUT HERE, I CAN SEE. TAKE MY HAND. FOLLOW ME.

The wording recalled lines from one of the rhymeless poems Joseph had found on Chevy’s computer after the boy left to live with his mother. Joseph wondered who was behind printing and selling T-shirts of the boy’s scribble. He could fathom neither the culprit nor the youth whose skateboard cut through an alley angling toward Reagan Square. He heard no more chanting from the core of the compound either—if it had ever been more than a figment of the skateboarder’s imagination. There was only an echo of the translations of freedom and love and life . He wondered whether the skateboarder repeated the words while scooting off, singing another protest chant. Had he ever even mentioned love? The father tossed his Coke can into a recycling bin at alley’s edge.

His street-cleaning team perched at curbside, behind their electric municipal truck and its twelve-foot trailer, hiding themselves and their equipment from the rush-hour pedestrians in the square.

“You’re doing late shift, Joe.” Ali wielded no more authority within the compound’s officialdom than the others, yet he spoke louder than the center-square din, in the tenor of something more than a question: between a suggestion and a rough bit of advice for the most senior crew member. He continued, “Tonight’s your turn, all yours.”

Joseph glanced toward his chest, and his hand idly brushed the red-and-blue municipal badge stitched high on his work suit. “It’s Tuesday. I was just out here Sunday night.”

“So what?” Ali barked.

Sensing his compromised position, Joseph gazed at the white stone beneath them as he responded. “There’s still four of us.”

Marta and Harold interrupted their fiddle with the cumbersome water sprays and concrete blasters leaned between the corner and their electric truck. They watched Joseph in the corners of opposing eyes. “Can’t hold any of us accountable for this,” said Harold.

“But you,” Marta blurted in Joseph’s direction, “that’s something else. Can blame you and yours all day, hey?”

Joseph swallowed the first response to his mind. His eyes trailed along the sidewalk. The others did not continue their argument—Marta and Harold pushed the oblong cleaning machines along a ramp and into the municipal truck’s trailer, and Ali peeked around the cabin, watching as the rush-hour pedestrians faded, solemnly replaced by battalions of university youths, toting signs scrawled with demands that dripped blood—calling for recognized “dreams” and “hopes” and “changes” and “acts,” lest they begin “tearing down these walls” in their left fists, while their rights tossed cigarette butts off into the cracks and corners of the compound’s main square.

Читать дальше

![Lord Weller - Ритера или опасная любовь [СИ]](/books/421202/lord-weller-ritera-ili-opasnaya-lyubov-si-thumb.webp)