Then Sharon heard the shriek of the metal as it scraped against the basement floor, she saw the shiny flap of that metal as Hayleigh wrenched it back with experienced fingers, and she smelled a dirty, earthen smell, dark and wet and cold and final. Something pushed hard at her back and something smashed against the side of her head and Sharon was falling, falling bluntly and heavily, like a rocket from the sky.

About “Hayleigh’s Dad”

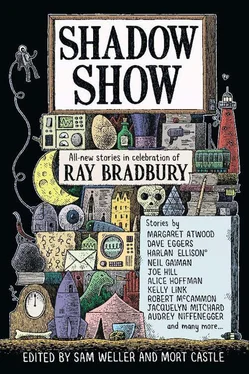

With Ray Bradbury, I ate dessert first. That is, as a kid with an insatiable literary sweet tooth, I devoured the science-fiction stories and the thrilling tales, inhaling them with awe and gusto the same way I gorged on Tootsie Rolls and Caravelle candy bars, reveling in The Martian Chronicles and The Illustrated Man . Later, as an adult, I came to the main course: the novels and the essays—and those same short stories upon which I had feasted as a child. Now, however, I could appreciate the artistic rigor that had gone into making them seem so effortlessly tossed off. They read like facts of nature, not like written works, which is the surest proof of Ray Bradbury’s phenomenal, cloud-topping imagination: His stories feel inevitable.

The direct inspiration for “Hayleigh’s Dad” is “The Whole Town’s Sleeping,” a diabolically creepy Bradbury story whose ending left me limp with exhaustion and buzzing with fear. Never before or since has a story taken hold of me in quite that way. As I read it the first time, it gripped my arm and carried me along, trusting and compliant—and then, at the end, it yanked the solid earth right out from under me and tossed me into darkness. I flailed. I gasped. And subsequently wondered what clever alien species had, under cover of night, delivered this bespectacled wizard to our unsuspecting world, this “Ray Bradbury,” this genial genius, this possessor of magical powers and inimitable narrative derring-do.

Discovering Ray’s book of essays Zen in the Art of Writing was a major turning point in my literary ambitions. He gave me permission to dream, to be bold, to take off the training wheels and snip the line tethering me to convention and propriety. “For the first thing a writer should be,” he declared, “is excited. He should be a thing of fevers and enthusiasms,” whose words “slammed the page like a lightning bolt.” My fingertips still sizzle when I recall this passage.

To those aliens who gave us Ray Bradbury—what other plausible origin could there be for this brilliant, dazzling craftsman and poet, except one involving extraterrestrial intervention?—we ought to say thanks, and to make it very, very clear that they can’t have him back.

—Julia Keller

When I was a kid in the suburbs of Chicago, during the summer we’d go to Quetico Provincial Park up on the border of Minnesota and Canada. “Provincial” implies that the place was small, but Quetico was, and still is, a million-acre nature preserve—so big you could go days and days without seeing another soul.

We would go on camping trips up there—weeks of canoeing and portaging, spotting bears and moose and deer, sleeping under star-soaked skies. The park was isolated and so pristine that you could actually drink the water straight from the lakes. You’d stick your paddle in, tilt the wide part to the clouds, and let the water run into your mouth.

I miss Quetico, but I won’t be going back anytime soon. Not after what happened to a girl named Frances Brandywine.

This was a few years ago. Frances was seventeen at the time, black-haired and with a reckless nature, determined always to leave the well-trod path, to break new ground and be alone.

Frances was up in Quetico with her family, in a remote part of the park, camped on the shore of one of the deeper lakes—a lonely body of dark water carved millions of years ago by a passing glacier.

One night, after her family went to bed, Frances took the rowboat out, planning to find a quiet spot in the middle of the lake, lie on the bench of the boat, look up at the sky, and maybe write in her journal.

So she left the shore and rowed for about twenty minutes, and when she was satisfied that she was over the lake’s deepest spot, she lay down and looked up at the night sky. The stars were very bright, the aurora borealis shimmering like a neon lasso. She was feeling very peaceful.

Then she heard something strange. It was like a knock. Clop clop .

She sat up, guessing that the boat had drifted to shore and run aground. But she looked around the boat, and she was still a half mile from shore. She leaned over the side, to see if she’d hit anything. But she saw nothing. No log, no rocks.

She lay back down, telling herself that it could have been any number of things—a fish, a turtle, a stick that had drifted under the boat.

She relaxed again, and soon fell into a contented reverie. She had just closed her eyes when she heard another knock. This time it was louder, a crisp clok clok clok . Like the sound of someone knocking hard on a wooden door. Except this knocking was coming from the bottom of the boat.

Now she was scared. She leaned over the side again. It had to be an animal. But what kind of animal would knock like that, three short, loud knocks in rapid succession?

Her mouth went dry. She held on to each side of the boat, and now she could only wait to see if it happened again. The silence stretched out. A few minutes passed, and just as she began to think she’d imagined it all, the knocks came again. But this time louder. Bam bam bam!

She had to leave. She lunged for the oars, got them into place, and began rowing. The water was very calm, so she should have made quick progress. But after rowing feverishly for minutes she looked around and realized, with cold dread, that she wasn’t moving at all. Something was keeping her exactly where she was.

Her mind clawed through options. She thought about leaving the boat, swimming to shore. But she knew the water was so cold that she’d freeze before getting far. And besides, whatever was knocking on the bottom of the boat was in that water.

Again she tried rowing. She rowed and rowed, on the verge of tears, but she went nowhere.

She stopped. She was exhausted. Her heavy breathing filled the air. She cried. She sobbed. But soon she calmed herself, and the boat was silent again. For ten minutes, then twenty. Again she tricked herself into thinking she’d imagined it all.

But just like before, just when she was beginning to get a grip on herself, the knocking came again, this time as loud as a bass drum. Boom boom boom! The floorboards of the boat shook with each strike.

Now she made a bad decision. She decided to lower one of the oars into the black water, trying to feel if there was some landmass, even some creature she could touch. As soon as the oar had broken the water’s surface, though, she felt a strong, silent tug at the other end and the oar was pulled under.

She screamed and jumped back. Now she had no options. All she could do was sit, and hope, and wait. Wait for the morning to come. Wait for whatever was going to happen to happen.

The knocking went on through the night. Sometimes it was sudden and loud: bam bam bam! And sometimes quieter: tap tap tap . Every so often it was almost musical: knock knock kno-ahk .

She passed the time writing in her notebook, recording each sound, each strike. And it’s only because of this notebook that we know what happened that night. Frances can’t tell us. She was never seen again.

The boat was found on shore the next day, empty but for the journal. On those pages were her frantic jottings, all written in her distinctive hand.

Читать дальше

![Lord Weller - Ритера или опасная любовь [СИ]](/books/421202/lord-weller-ritera-ili-opasnaya-lyubov-si-thumb.webp)