The captain says through the lieutenant’s translation, “Surely you understand my position. As commander of this ship, I cannot call someone else Boss.”

I shrug. I expected this. “Then call me what you will.”

His lips twist into a slight smile, and the game is on. He now knows I’m only going to tell him what I want to tell him and nothing more.

“Fahd Al-Nasir will do his best to translate for me,” I say.

No one has said anything about my knife, which surprises me.

“I have a team of linguists monitoring the conversation,” the captain says. “They might be able to assist if we need it.”

“A team of linguists,” I say. “I am impressed. How large is your crew?”

“Five hundred strong,” he says.

Five hundred. The number staggers me.

“We guessed perhaps a hundred,” I say.

“You’ve never encountered one of our ships before?” he asks.

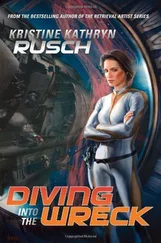

I’m going to be as honest as I can with him, unless I believe some of the information is not to our advantage. “Not a working vessel,” I say.

He frowns. That answer clearly disturbs him. “How many of our ships have you encountered that don’t work?”

“Five,” I say.

“Five,” he repeats, then holds out his open hand. “Five?”

“Yes,” I say.

“Do they have any crew?” he asks.

I study him for a moment. He expects Dignity Vessels to have a crew. I expect them to be abandoned and ruined. Something is quite off here.

“No,” I say. “They have all been abandoned.”

The lieutenant touches her ear. She repeats my word again. Clearly the linguists are working on it.

“They’re empty,” I say to him. “The ones I find are derelicts.”

The lieutenant looks at me, her face a little slack, not from the linguists nattering in her ear, but from my words.

“Empty,” she repeats. “Destroyed?”

“A couple of them,” I say. “I don’t know if they were ruined by time or by some kind of battle.”

“You found them all in the same area of space?” she asks, her Standard fluid.

“No,” I say.

She looks away from me, blinks hard, and frowns. The captain says her name sharply. She nods but doesn’t look at him. Then she swallows visibly.

My words have disturbed her.

The captain asks her something in their language. Al-Nasir answers, slowly, trying to translate my words.

The lieutenant raises her hand, as if asking for a moment. Her palm is shaking.

She then turns to the captain and speaks rapidly. Al-Nasir leans forward as if he’s trying to understand.

The captain’s frown deepens, and he looks at me. He says something to the lieutenant, clearly meaning for her to translate.

“How long abandoned?” she asks.

“We don’t know exactly,” I say.

She repeats this. The captain speaks. She translates: “You have a guess.”

I shrug a shoulder. This seems momentous to them.

“Please,” he says to me in Standard. “Please.”

That moves me more than I expect. Beneath this show of diplomatic courtesy, beneath the rigid military behavior, beneath the patience of the past two weeks lives panic.

I have just tapped into it.

And I think I’m about to make it worse.

“My guess is based on what little we know about Dignity Vessels,” I say. “We believe they’re legend. Myth.”

The lieutenant translates. The captain looks surprised. He narrows his eyes and looks at me. Then he nods, asking me to continue.

Maybe the mood in the room is catching, because I’m suddenly nervous. “The ships we’ve found are at least five thousand years old.”

The lieutenant doesn’t translate. She tilts her head and looks at me as if I’m crazy. I feel crazy.

“I know it sounds impossible,” I say. “We have no evidence that the Dignity Vessels could travel more than fifty light-years from Earth. But clearly you’re here, and they got here, and something enabled you to get here. But we’ve done studies on all of the ships we’ve found—not just us, but the Empire, too, and we know those ships are at least five thousand years old, maybe older.”

She still doesn’t translate. Her mouth is open slightly.

The captain says her name. She doesn’t respond. He says her name again, then touches her shoulder. He says something else.

Al-Nasir leans into me. “He’s asking her if she needs to leave, if they need to bring in someone else.”

She’s shaking her head. She rubs a hand over her mouth, squares her shoulders just like Al-Nasir did before we got on the ship, and then she speaks for several minutes to the captain.

He repeats a phrase a couple times. I don’t need Al-Nasir to tell me that the captain is asking about my numbers, about that five thousand years.

He turns to me, his lips thin, his eyes steely. He’s not angry. He’s not upset like the lieutenant is. But he’s disturbed and trying to hide it.

He asks something with a great deal of intensity, the words sharp and hard.

“How long has this base been empty?” the lieutenant asks slowly, as if she’s afraid of my answer.

“I don’t know,” I say.

“What do they say in—?” and then she uses a phrase I’ve never heard. Before I can ask her to clarify, Al-Nasir says, “Vaycehn. She’s asking about Vaycehn.”

“What do they say about the base in Vaycehn?” I ask. “They have no idea it’s here.”

The captain speaks without her. “You know.”

I understand him. He’s not commenting. He’s asking. How did I know the base was here?

I try to think of a way to answer him, one that will be understandable without a lot of explaining in languages neither of us completely understand.

“We didn’t know,” I say. “This place surprised us.”

That much is true. I brace myself for the next question, trying to figure out how to explain energy signatures and death holes and all of those problems in a way that the lieutenant and those unseen linguists could understand.

The captain asks his question, and the lieutenant translates.

“How long has—Vaa-zen—been here?” she asks, mispronouncing Vaycehn.

“Here?” I ask. “On Wyr? This planet?”

She nods.

“It’s the oldest city in the sector,” I say, stalling because I know instinctively that he’s not going to like the answer. “Vaycehn has been here more than five thousand years.”

~ * ~

Five thousand years. The woman who wouldn’t tell him her real name kept saying five thousand years.

The woman watched him, concern on her face. Coop had a hunch she understood more than she was saying. Al-Nasir had his hands clasped, his forehead creased with worry.

And Perkins fidgeted beneath the table, having as much difficulty as Coop, but in a different area. She believed the number.

He did not.

Five thousand years just wasn’t possible. At least that was what his logical brain told him.

But his subconscious kept whispering that five thousand years was possible. The anacapa could have malfunctioned badly. No one knew exactly where it would take people when it did malfunction. That was the danger of the Fleet vessels.

Coop shook his head slightly, banishing that thought which snuck into his mind. He wasn’t going to deal with that, not now.

He had another problem to deal with first.

“She keeps saying the same phrase over and over,” he said to Perkins. “You’re translating that as five thousand years. Are you sure you’re right?”

She looked at him. The terror in her eyes was answer enough. But she said through her comm link, “Please check that phrase through the system again.”

Coop had already told the linguists this conversation would have to remain secret. But he wasn’t sure about something this big. It would be hard for anyone to keep it secret.

Читать дальше