“One-point-two million visitors a year,” says Gregory, “and those are the official ones.”

It seems he has gotten the tourist lecture too.

“We’d be considered unofficial, even though we have a guide. We’re not here on vacation.” Gregory sounds surprised at that, as if he doesn’t understand the limiting of the word “tourist” to vacationer alone.

“Was your friend able to tell you anything unofficial?” Bridge asks.

Lentz’s grin grew. “Well, two old friends, you know, we’ll talk about anything.”

My breath catches. Lentz got some information.

“And we did. We talked about our friends, our colleagues, our research.”

Stone sighs, as if she wants him to hurry to the point.

He leans back in the chair and puts his hands behind his head. “My friend is researching the death holes.”

Lentz has everyone’s attention now, and he seems to be enjoying it.

“It seems that the Boss’s guess was right. Others have died here, all through Vaycehn’s history. In fact, one of the reasons the city center moved so much was to avoid the holes.”

“There are that many?” Stone asks. “I thought there were only a few.”

“All through the city’s history,” Lentz says, “areas just collapse. It’s not the weight of buildings or the ground above that causes it—although sometimes that happens too. But there are entire death hole areas in the Basin. That’s why some of the ruins are off-limits to tourists, and that’s why some of the history of the city is vague.”

Bridge has steepled his fingers. I’m wishing I knew more detail about the five-thousand-year history of Vaycehn, like how often the city center moved and where.

“He thinks there’s a scientific reason for all of this?” Carmak asks. Her eyes are sparkling. She’s not the same woman who was in the field this afternoon. “Besides a geologic one, I mean. Because the histories say that Vaycehn was initially built on unstable ground, and the oldest colonists had no way to know where the stable ground was. They searched until they found an area that could support their city.”

“Sounds plausible, doesn’t it?” Lentz says. “Until you remember that humans aren’t native to this place. The colonists had enough scientific skill to travel through space, then colonize this area and begin to farm it. You’d think they could figure out rudimentary geology.”

“Science doesn’t always follow a linear path,” says Ilona, but she’s frowning. She’s thinking about this.

Both Mikk and Stone are restless. But I’m fascinated. I have to force myself to eat some of the food on my plate. Not even the tastes are familiar, except on a basic level—bitter, sweet, salty, bitingly spicy. I pick at what’s before me, then push the plate away.

“Well,” Lentz says with a small shrug, “whether or not you agree with the premise for his research doesn’t matter. He started the work because he didn’t believe his own country’s history.”

I’m glad Lentz is the one describing this. Gregory doesn’t have the people skills, and Ilona is too invested in Vaycehnese life.

“He dug through old records and found a lot of the basic stuff you’re talking about, Lucretia. He found the measurements, as well as stuff on whether the ground is stable, whether or not there’s bedrock, how deep the solid layer goes before they find ground water, all of that kind of thing.”

”And?” Mikk isn’t even trying to mask his irritation at the way the scientists present things.

“And,” Lentz says, “the old studies confirm what he suspected.”

”Which is?” Mikk asks.

”That these death holes appear in solid ground. The catacomb of caves here were created by the phenomenon that creates the death holes. And it’s ongoing.”

”Like volcanic activity?” Stone asks. Now she’s intrigued.

”Not quite,” Lentz says. “Because there’s always a history of volcanic eruptions in the past.”

”Maybe a groundquake, then,” she says.

“On an unknown fault line, maybe?” Carmak asks.

I shake my head. Even I know this. We have the capability to map tectonic plates from space. There are no unknown fault lines on any settled planet.

I’m about to say that when Lentz shakes his head.

”It’s more like an explosion from underground,” he says. “With a directed charge, made to create a hole in the surface above.”

”Have they gone down to check what causes the explosion?” Bridge asks,

”Initially,” Lentz says. “Which is why they’re called death holes.”

“Because the investigators mummify,” Mikk says,

Lentz shakes his head. “Because the investigators vanish.”

”Vanish?” I frown at him. He’s enjoying dragging this out. “What does that mean?”

“It means that they’re never found,” he says.

”Does anyone search for them?” I remember how reluctant the guide was to let me down the corridor.

”Not after the first one or two don’t make it back,” he says. “Then they use animals to test. Usually after a dozen years or so have passed, something survives, and then it’s deemed safe. But until then, no one goes in the death holes.”

”Sounds like they learned about these places the hard way,” Ilona says.

Everyone turns toward her, as if her statement is obvious.

“I mean,” she says, “they have a protocol and a name for the phenomenon. So that means that these holes repeated, and then after a while, they needed a way to deal with them.”

“Ilona’s right,” Bridge says. “A culture doesn’t name a phenomenon if it’s extremely rare. And it doesn’t create a protocol if the phenomenon happens once every hundred years or so. How many of these have there been?”

Lentz shrugs. “I didn’t talk to him all day.”

“But you found out a lot,” I say, wanting him to continue. “Does he think it’s odd that these places eventually become safe?”

“No,” Lentz says. “He says it validates his theory, that some kind of gas or something builds up and then explodes. It then dissipates over time, and the hole becomes safe.”

“If there was gas, it would be released into the atmosphere, contaminating the area around it,” Gregory says. “Did he find that?”

“He’s only had two death holes to study since this became his expertise. But the records don’t show any areawide deaths.”

“Because,” Ilona says, “they clear the areas when a death hole appears. You told us that.”

“History tells us that,” Carmak says.

“I’d like to know what happened the first time a few death holes appeared,” I say. Because it doesn’t have to be a gas. It could be a field. An expansion of a stealth-tech field—a different kind than we experienced in the Room of Lost Souls, but an expansion nonetheless.

Still, I don’t say that. I’m still not willing to admit this place is tied to ancient stealth. We haven’t seen stealth tech act like that.

Or have we?

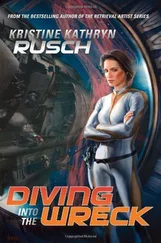

I turn to Gregory, whom I hired because he once specialized in stealth tech. He was one of the government scientists who tried to reverse-engineer stealth tech with Squishy.

“When you guys were trying to re-create stealth tech in the lab,” I say to him, “did you get some localized expansion phenomena? Something that would resemble what’s going on here?”

He sighs. He hates talking about that time. What Squishy told me in as little detail as possible was that in the two hundred years the Empire has been trying to re-create stealth tech, the program has lost ships, materiel, and people.

When he remains silent, I add, “Squishy told me that a lot of people died while she worked on the program. I assumed they got trapped in the stealth-tech field. Is that what happened? Or were there ‘explosions’ to use Lentz’s word? Did the field expand unexpectedly?”

Читать дальше