“Thank you,” the Lieutenant said. “Just a couple more questions now. Miss Graves said Mrs. Groener had tried suicide before. Do you know anything about that?”

Mrs. Labelle laughed. “That was a false alarm. A few months ago he found her almost passed out with an empty bottle of sleeping pills beside her. He started to force warm water down her and he’d just got the waste basket for her to throw up in when he noticed the sleeping pills scattered at the bottom of it. She just wanted to make him think she’d swallowed them. People are funny, aren’t they? What’s the other question?”

“Miss Graves said that yesterday she saw Mrs. Groener drinking—in your sunroom, she said—with her left wrist tied to the arm of her chair with her scarf. Know anything about that?”

“No, it sounds pointless. The sunroom’s that alcove behind you, officer, with the big windows. Wait a minute—I do remember seeing Mrs. Groener do that years ago. It was Oklahoma. It was sold out. We were sitting in the second balcony, and she had her scarf wrapped around her wrist and the arm of her seat. I thought she’d done it without thinking.”

“Huh!” The Lieutenant stood up and started to pace. He noticed Mrs. Labelle. “That’ll be all,” he told her. “When you go back to the dining room would you ask Mr. Groener if I could see him again?”

“I certainly will,” Mrs. Labelle said, popping up with another flash of leg. She smiled and rippled her eyelids. “You gentlemen have given me some fascinating sidelights on life.”

“You’re certainly welcome,” Zocky assured her, gazing after her appreciatively as she click-clicked down the hall. Then he said to the Lieutenant, “Well, that kills my theory of a suicide trigger. I guess Groener really is the pious type who’d never get out of line.”

“Yeah,” the Lieutenant agreed abstractedly, still pacing. “Yeah, Zocky, I’m afraid he is, though ‘pious’ may not be just the right word. Scared of stepping over the line comes closer.”

“But this Labelle’s a real odd cookie—reminds me of that holdup girl last month. She thinks everything’s funny.”’

“You got a point there, Zocky.”

“A real bright-eyes too, despite her barbiturates and booze.”

“Some it takes that way, Zocky.”

“Of course she’s real attractive for her age, but that’s not here or there.”

“Maybe not, Zocky.”

“You know what? When you talked to her about Groener’s supposed mistress I think she thought you meant her.”

“Okay, okay, Zocky!”

When Groener arrived, looking more tired than ever, the Lieutenant stopped pacing and said, “Tell me, did your wife have many phobias? Especially agoraphobia, claustrophobia, acrophobia? Those are—”

“I know,” Groener said, settling himself. “Fear of open spaces, dread of being shut in, fear of heights. She had quite a few irrational fears, but not those particularly. Oh, perhaps a touch of claustrophobia—”

“All right,” the Lieutenant said, cutting him short. “Mr. Groener, from what I’ve heard tonight your wife didn’t commit suicide.”

Groener nodded. “I’m glad you understand alcoholics aren’t responsible for the things they do in black-out.”

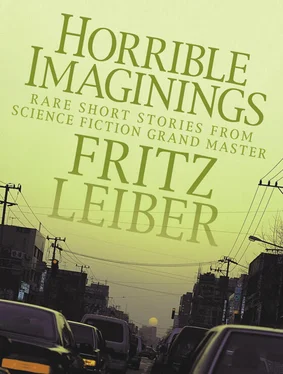

Horrible Imaginings

“She was murdered,” the Lieutenant finished.

Groener frowned at him incredulously.

“I’ll give you a quick run-down on what really happened tonight, as I see it, and you can tell me what you think,” the Lieutenant said.

He started to pace again as if he were too wound-up not to. “You went for your coffee. Mrs. Labelle called to you through her door as you passed. You didn’t want any of her child psychology—or anything else from her either. But it told you she was wide awake and listening to everything. Then you came to Miss Graves’s bedroom and the door was open and you saw her sleeping quietly, her silver fleece of hair falling across the pillow.”

Groener shook his head and moved his spread-fingered left hand sideways. But the Lieutenant continued, “It struck you how you’d wasted decades of your life caring for and being faithful to a woman who was never going to get well or any more attractive. You thought of what a wonderful life you could have had if you’d taken another direction. But that direction was closed to you now—you’d been spoiled for it. You’d built up inhibitions within yourself that wouldn’t let you overturn the applecart. If you’d tried to, you’d have suffered agonies of guilt and remorse. It would have killed all enjoyment. So you closed Miss Graves’s door, because you couldn’t bear to watch her.”

“Wait a minute—” Groener protested.

“Shut up,” the Lieutenant told him dispassionately. “As you closed the door you felt a terrific spasm of rage at the injustice of it. All of that rage was directed against your wife. You’d had feelings like that before, but never had a situation brought them so tormentingly home to you. For one thing you’d just been treated like a worm by the woman you were tied to in front of the woman you desired with a consuming physical passion. It was tearing you apart. You’d come to the end of your rope of hope. Five years had fully demonstrated that your wife would never stop drinking or mentally intimidating you.

“You thought of all the opportunities of happiness and pleasure you’d passed up without benefit to her, or yourself—or anybody. You suddenly saw how you could do it now without much risk to yourself, and how afterwards perhaps everything would be different for you. You could still take the other direction. What you had in mind was bad, but your wife had been asking for it. You knew you could no longer ever get free without it. It was a partly irrational but compulsive psychological barrier that nothing but your wife’s death could topple. The thought of what you were going to do filled you like black fire, so there was no room in your mind for anything else.”

“Really, Lieutenant, this—”

“Shut up. Your plan hung on knowing Mrs. Labelle was awake—that and knowing that she and Miss Graves were both on to your wife’s screaming trick, if that should come up. You started making coffee—and even more noise than you usually do—and then you took off your slippers and you walked back to the bedroom without making a sound. Or if you did make a few slight, creaking-floorboard sounds, you figured the wind-chimes would cover them up.

“Yes, Mr. Groener, you’re a man who normally makes a lot of noise walking, so your wife wouldn’t accuse you of sneaking around. So much noise, in fact, that it’s become a joke among your friends. But when you want to, or even just when your mind’s on something else, you walk very quietly. You did it earlier this evening right in front of me when you went in the bedroom. You disappeared that time without a sound.

“You found your wife asleep, still passed out from the drinks. You carefully moved back what light furniture and stuff there was between the bed and the wide-open window. You wanted a clear pathway and it didn’t occur to you that a drunk going from the bed to the window under her own power would have bumped and probably knocked over a half dozen things.”

The Lieutenant’s voice hardened. “You grabbed your wife—she got out one scream—and you picked her up—she weighed next to nothing—and you pitched her out the window. Then you stood there listening a minute. This was the hump, you thought. But nobody called or got up or did anything. So for a final artistic touch you put your wife’s bedtime drink and one of her burnt-out lipstick-stained cigarettes on the windowsill. You’ve got to watch out for artistic touches, Groener, because they’re generally wrong. Then you glided back to the kitchen, finished the coffee act, and came back noisy.”

Читать дальше