“Rick!” Hawk’s voice sinuously seeks me from behind.

I lower my head and bull forward.

“Ricky, look out!”

I register what my eyes must have seen all the time. The bus. The driver, wide-eyed and staring upward. The rushing chrome bumpers—

I feel no pain at first. Just the brutal physical force, the crushing motion, the slamming against the pavement. I feel—broken. Parts of me are no longer whole, that I know. When I try to move, some things don’t, and those that do, don’t move in the right places.

I am lying on my back. I think one leg is twisted beneath me.

Come to me, ship …

One of the swooping, agitated, alien ships has parked poised, stationary above the block, above the street, above me. It masks both the city glow and the few stars penetrating that radiance. The angles are peculiar. Hawk’s face enters my field of vision. I expect him to look stricken, or at least concerned. He only looks—I don’t know— possessive, a boy whose doll has broken. Other faces now, all staring on with confusion, some with a sort of interest. I saw those faces at the party, those expressions.

As I stare past Hawk at the immobile alien ship, I know that I am dying here in the street. And I was on the way to Oregon…. Why is the alien ship above me? They’ll start somewhere, Hawk had said. Sometime. With someone.

Then I feel the ice. At least I can feel something. I feel that knotted— something, an agency from outside me coming within, a chilly intrusion into my core.

The ship seems closer, dwarfing everything else, monopolizing my vision. They’ll give us the word, Hawk had said. I had wanted the word. Now I feel very tight and unwilling.

From deep inside, spreading, flexing, tearing, ice impales me. The cold burns with a flame. I try to shrink away from it—and cannot. And then something moves. My foot. It spasms once, twice. My ankle jerks. My knee separates, cartilage wrenching apart, sliding back together, but wrong. My whole body quivers, each limb rebelling. Joints grind.

But I start to move. Slowly, horribly, without my orders, I rear up. Stop it, I will myself. I can’t stop it.

I wonder if the aliens define featherless bipeds too?

The faces around the mirror pain as my body struggles to its knees. No one watches the ship anymore. All eyes fix on my performance.

I am called… At last I am wanted.

Why aren’t I dead? I’m moving and I cannot help it. My body lurches to its feet, limbs pivoting at wrong, odd angles. The fist inside me tentatively twists. I struggle to fall, to rest, but I am not allowed the luxury of ending this. Death doesn’t save me. I waited too long and forfeit escape. At least I finally tried. It isn’t fair, but then it never was.

The fist in me flexes, testing again.

My eyes flicker. Hawk has come to me. He watches with impassive eyes of shining black metal.

What do aliens want?

Chickens, dancing.

The path to publication for “Dancing Chickens” was odd and twisted—just as, some will say, the story itself is.

We’ll start with Leigh Kennedy. Back before Leigh was a successful novelist living in Britain, she rose as a shining star in the firmament of the Northern Colorado Writers Workshop. The workshop has been around for at least a decade and a half, and has included such members as Connie Willis, Dan Simmons, Steve Rasnic Tem, Simon Hawke, John Stith, Vance Aandahl, and David Dvorkin. One day Leigh Kennedy was musing about a childhood memory: as a little girl in her mother’s kitchen in Central City, high in the Colorado Rockies, Leigh had discovered the pleasures of sticking her hand inside whole uncooked chickens and making them dance like puppets. True, you had to crack the joints on the legs and wings, and the tactile sensation was pretty icky, but there was a certain Gregory Hines appeal to the whole process. This was long before similar dancing chickens appeared on the TV comedy series, “Fridays,” and the image was indelibly encoded in my neurons.

Then there was the Al Pacino movie, Cruising. Controversial, in part, because of its depiction of gay leather bar culture, the film introduced the quaint custom of fist-fucking to mainstream audiences. My kid brother and I saw the movie in a now-shuttered movie palace in downtown Cheyenne, and noted the audience seemed something less than enthusiastic.

At some point before all this, I had been enormously impressed by Robert Silverberg’s Nebula-winning “Passengers,” a grimly powerful story of humans manipulated by alien forces. That emotional charge stuck with me.

Sometime early in 1981 I put fingers to typewriter keys and forced this story out. Although much of the reaction of my fellows in the writing workshop was positive, adjectives such as repulsive, morbid, and depressing were also tossed around. I felt some pessimism about the story’s commercial prospects.

Then, close to Christmas, editor Marta Randall cheerfully bought the story for New Dimensions 13. I discovered I was in the company of such contributions as Vonda N. McIntyre’s “Superluminal” and “Flying Saucer Rock and Roll” by Howard Waldrop. I was happy.

Pocket Books scheduled the anthology for its June 1982 list. Advance copies were sent out to reviewers. And then, true to the books series number, it was canceled. The official word was that too few advance sales had been generated to warrant publication.

Marta regretfully returned the rights to the story to me.

In the meantime, Michael Bishop had been bugging me about contributing an original to his Light Years and Dark anthology, a project intended to be both comprehensive and daring. I sent him “Dancing Chickens.” Michael didn’t like the story at all and returned it with kind, but final words.

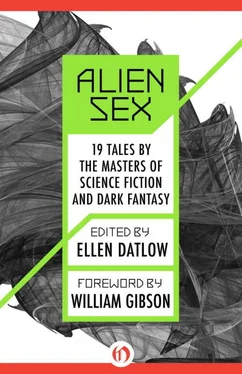

Somewhere along the line, Ellen Datlow saw the story at OMNI and bounced it, saying it was dynamite but entirely too raunchy for the magazine. Then, hearing of the Bishop rejection, she did me a great kindness. She took it upon herself to persuade Michael to read the piece again. He did, decided he liked the story better than before, and reversed his first decision. “Dancing Chickens” finally appeared in Light Years and Dark late in 1984. It hasn’t been reprinted since.

Not all stories, of course, go through these Byzantine turns. But fictions are like kids, and some are more difficult than the others. I’m talking content here, too—not just marketing glitches. I hope you found “Dancing Chickens” as difficult a child to read as I did to write.

EDWARD BRYANT

ROADSIDE RESCUE

PAT CADIGAN

Pat Cadigan sold her first professional science fiction story in 1980 and became a fulltime writer in 1987. She is the author of fifteen books, including two nonfiction books on the making of the films Lost in Space and The Mummy , one young adult novel, and two Arthur C. Clarke Award–winning novels, Synners and Fools . She has spoken at universities, literary festivals, and cultural gatherings around the world, including lectures at Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Massachusetts; the PopTech conference in Camden, Maine; the Utopiales science fiction festival in France, and the Pio Manzù Research Centre in Italy. She lives in North London, can be found on social media, and tweets as @cadigan. Most of her books are available electronically.

BARELY FIFTEEN MINUTES AFTER he’d called Area Traffic Surveillance, Etn Carrera saw the big limousine transport coming toward him. He watched it with mild interest from his smaller and temporarily disabled vehicle. Some media celebrity or an alien—more likely an alien. All aliens seemed enamored with things like limos and private SSTs, even after all these years. In any case, Etan fully expected to see the transport pass without even slowing, the navigator (not driver—limos drove themselves) hardly glancing his way, leaving him alone again in the rolling, green, empty countryside.

Читать дальше