"Paula says you haven’t been to class in weeks," she told him. "She says you might even flunk out."

Jeff beamed, took her hand. "Is that all? Honey, it doesn’t matter. I’m quitting school anyway. I just won seventeen thousand dollars, and by October I can make … Look, it’s nothing to be concerned about. We’ll have plenty of money; I’ll always see to that."

"How?" she asked bitterly. "Gambling? Is that how we’d live?"

"Investments," he told her. "Perfectly legitimate business investments, in big companies like IBM and Xerox and—"

"Be realistic, Jeff. You got real lucky on one horse race, and now all of a sudden you think you can strike it rich in the stock market. Well, what if the stocks go down? What if there’s a depression or something?"

"There won’t be," he said quietly.

"You don’t know that. My daddy says—"

"I don’t care what your daddy says. There isn’t going to be any—"

She set her napkin down, pushed her chair back from the table. "Well, I do care what my parents say. And I hate to even think how they’d react if I told them I was getting married to an eighteen-year-old boy who’s dropped out of school to be a gambler."

Jeff could think of nothing to say. She was right, of course. He must seem an irresponsible fool to her. It had been a terrible mistake to tell her what he was doing.

He slipped the ring back in his jacket pocket. "I’ll hold on to this for now," he said. "And maybe I’ll reconsider about school."

Her eyes went moist again, their vivid blue shimmering through the layer of tears. "Please do, Jeff. I don’t want to lose you, not because of some craziness like this."

He squeezed her hand. "You’ll wear that ring someday," he said. "You’ll be proud of it, and proud of me."

They were married at the First Baptist Church in Rockwood, Tennessee in June of 1968, the week after Jeff received his M.B.A. Just four days before the date he’d met Linda—twice, with such drastically different outcomes—in those other lives. Rockwood was Judy’s hometown, and the reception her parents threw afterward was a big, informal barbecue at their summer place on nearby Watts Bar Lake. Jeff noticed that his father’s cough was getting worse, but still he wouldn’t listen to his son’s entreaties that he stop chain-smoking Pall Malls. He wouldn’t quit until the emphysema was diagnosed, years from now. Jeff’s mother was happier than she’d been at his weddings to Linda and Diane, though of course she had no memory of either occasion. His sister, a shy fifteen-year-old with braces on her teeth, had taken to Judy right away.

The Gordon family, likewise, had welcomed Jeff into the fold wholeheartedly. He had transformed himself into the very image of a perfect catch: twenty-three, good education, industrious, responsible. A nice little nest egg already set aside and a conservative but steadily building portfolio of stocks in his and Judy’s names.

It hadn’t been easy. The five years of school were tough enough, forcing himself back into the long-abandoned regimen of studies and term papers and exams; but the hardest part had been contriving not to get rich. The last time he’d been this age he’d been a financial wunderkind, the major partner in a powerful conglomerate. Such a sudden infusion of massive wealth would have thrown Judy off balance, would have created significant problems between them. So he’d passed up the Belmont and World Series bets entirely, and had painstakingly avoided the many high-yield investments with which he could easily have made another multimillion-dollar fortune.

He and Frank Maddock had drifted apart soon after the Kentucky Derby this time. His unknowing one-time partner at the pinnacle of corporate success had finished Columbia Law School and was now a junior attorney with a firm in Pittsburgh.

Jeff and Judy assumed the mortgage on a pleasant little fake-colonial house on Cheshire Bridge Road in Atlanta, and Jeff rented a four-room office in a building near Five Points that he’d once owned. Five days a week he put on a suit and tie, drove downtown, bid his secretary and associates good morning, locked himself in his office, and read. Sophocles, Shakespeare, Proust, Faulkner … all the works he’d meant to absorb before but had never had the time to read.

At the end of the day he’d dash off a few memos to his partners, recommending perhaps that they not risk investing in an unproven company like Sony, but should keep their gradually growing principal in something safe, such as AT&T. Jeff steered the small company carefully away from any sources of sudden wealth, made sure he and his associates remained comfortably but unspectacularly entrenched in the upper middle class. His partners frequently followed his advice; when they didn’t, the losses tended to balance out the gains, so the net effect remained as Jeff intended.

At night he and Judy would cuddle in the den to watch "Laugh-In" or "The Name of the Game" together, then maybe play a game of Scrabble before they went to bed. On warm weekends they’d go sailing on Lake Lanier, or play tennis and hike the nature trails at Callaway Gardens.

Life was quiet, ordered, sublimely normal. Jeff was thoroughly content. Not ecstatic—there was none of the sense of absolute enchantment he had felt in watching his daughter, Gretchen, grow up at the estate in Dutchess County—but he was happy, and at peace. For the first time, his long, chaotic life was defined by its utter simplicity and lack of turmoil.

Jeff dug his toes into the sand, raised himself to his elbows, and shaded his eyes from the sun with one hand. Judy was asleep on the blanket beside him, curled fingers still holding her place in a copy of Jaws. He gently kissed her half-open mouth.

"Want some Pina Colada?" Jeff asked as she stretched herself awake. "We’ve still got half a thermos left."

"Mmm. Just want to lie here like this. For about twenty years."

"Better turn over every six months or so, then."

She twisted her head to look at the back of her right shoulder, saw it was getting red. She rolled faceup, close to him, and he kissed her again; longer this time, and deeper.

A few yards down the beach another couple had a radio playing, and Jeff broke the kiss as the music ended and a Jamaican-accented announcer began reading about John Dean’s testimony that day in the Watergate hearings. "Love you," Judy said.

"Love you," he answered, touching the tip of her sun-pink nose. And he did, Lord God how he did.

Jeff allowed himself six weeks of vacation every year, in keeping with his pretense of a regular work schedule. The arbitrarily imposed limitation made the time seem all the sweeter. Last year they’d bicycled through Scotland, and this summer they planned to take a hot-air balloon tour of the French wine country. At this moment, though, he could think of no place he’d rather be than here in Ocho Rios, with the woman who had brought sanity and delight to his disjointed life.

"Necklace for the pretty missy, mon? Nice cochina necklace?" The little Jamaican boy was no older than eight or nine. His arms were draped with dozens of delicate shell necklaces and bracelets, and a cloth pouch tied at his waist bulged with earrings made from the same colorful shells. "How much for … that one, there?"

"Eight shilling."

"Make it one pound six, and I’ll take it." The boy raised his eyebrows, confused. "Hey, you crazy, mon? You s’pose go lower, not higher."

"Two pounds, then."

"I’m not gonna argue with you, mon. You got it." The child hurriedly took the necklace from his arm, handed it to Judy. "You wan' buy any more, I got plenty. Ever’body on the beach know me, my name Renard, O.K.?"

"O.K., Renard. Nice doing business with you." Jeff handed him two one-pound notes, and the boy scampered away down the beach, grinning.

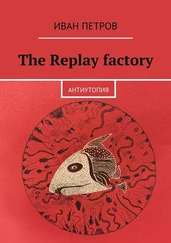

Читать дальше