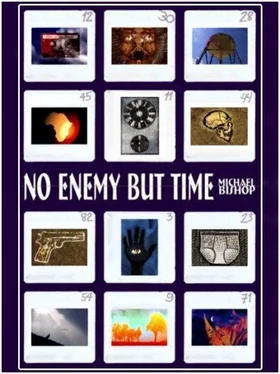

After their departure, the Grub and I were on our own again. I scrambled over the outcropping of tuff, searching for the spot where Kaprow had parked the omnibus.

There. There it was.

Suspended in the air as if by Hindu legerdemain, the Backstep Scaffold. I knelt beneath it and stared up into the interior of the bus, an equipment-crowded chapel of stinging white light. There were Kaprow’s Egg Beaters, huge coppery rotors, and enclosing them were the padded interior walls and ceiling of the omnibus. Deliverance.

“We’re going home, baby. Going home.”

I pushed the Grub up and over the edge of the Backstep Scaffold, which was about a foot above eye level, then chinned my way onto the platform and settled into its contours with my daughter in my left arm. It took me a moment to locate the toggle for retracting the platform, but when I found and activated it, the rotors inside the omnibus began to spin and the past to drop away beneath us like an ill-remembered dream. My baby and I were going home. Home.

Russell-Tharaka Air Force Base, Zarakal

September 1987

“ Welcomeback, Johnny. I was beginning to think you were going to sleep the rest of your life away.”

At first he did not recognize the face outlined above him against a window of robin’s-egg blue. The face was a gentle caricature of one he remembered from another time. Most disconcerting, its skin was pale, with hints of applied color in the cheeks and lavender crescents on the eyelids. His tongue would not move.

“Don’t try to talk yet, Johnny. You’ve been sedated for several days. I’ve… well, I’ve watched you sleep for the last three. Off and on, that is. They’ve given me a room in the Visiting Officers’ Quarters. First time I’ve ever had officers’ quarters in my life. Hugo would have scoffed at me for even accepting them—but noncoms’ widows don’t rate an on-base hostelry all their own and it’s better than trying to commute out here every morning from Marakoi.

“God, Johnny, they did everything they could to keep me out of this country, everything but charge me with a federal crime and lock me up in Leavenworth. Suddenly, though, just a few days ago, their resistance collapsed, and here I am…. I don’t think I’ve ever watched you sleep so many straight hours without your eyeballs disappearing up into your forehead. Maybe you’re over that now. Maybe that justifies what they’ve done to you. Maybe that absolves them of using you for a guinea pig in some sort of temporal I-don’t-know-what…. Woody Kaprow tried to explain it. He was the one who insisted on their letting me into the country once you got back from wherever the hell you supposedly were. I owe him for that, I know I do, but the rest of it—the secrecy, the deceptions, the bullyings, the run-arounds—God knows when I’ll be able to forgive them for that . God knows.”

The face was coming into focus, taking on a recognizable human aspect. It was an older face than he remembered, but he had not seen it for—well, for what?—eight years? ten years? more than two million?

It belonged to the woman who had raised him, an aging woman against whom he had perpetrated a terrible wrong, believing himself, at her hands, the victim of an unforgivable treachery. He had forestalled any future treachery by cutting all ties with her.

Now—whenever Now was—here she was again. He did not resent this torrent of words from her or even the implicit assumption underlying them, that they could resume their lives without agonizing over or even referring to the cause of their break. That was a false assumption, however. He had a good deal to answer for. He knew it, and he tried unsuccessfully to make his tongue work.

“No, really. You don’t have to say anything, Johnny. They said you might have trouble. Apparently you’ve awakened briefly twice before. Kaprow and a couple of Air Force doctors were with you, but you couldn’t talk. Not a word. They wanted a kind of deposition from you, I think. A debriefing document. You weren’t ready to give it. Flustered Kaprow lots, I’m afraid, even if at bottom he’s a reasonably decent fellow, one of the few people I’ve met who won’t duck the implications of his own responsibility for a fiasco like this one. He acknowledges his part in involving you, for instance. Blames himself for losing contact with you while you were gone, for the injuries you’ve sustained. Everyone else—Air Force brass, the local interior ministry, Defense Department officials back home—everyone else seems to be working on a C.Y.A. basis. They wanted a deposition attesting to the complete success and worthiness of this project…. You don’t even remember Kaprow and the others coming in here, do you? You ought to see your face—it’s an acting-class paradigm of Total Bewilderment.”

His mother gave a nervous laugh, wiped his forehead with a wet cloth, and leaned aside so that the African sky in the window overwhelmed him with its raw immensity. A jet fighter flashed by from left to right, as if it had just taken off from a nearby runway, but the sound of its engines was muted by the hum of the air-conditioning and the thickness of the walls in the cavelike hospital room.

C.Y.A. meant “cover your ass,” an old and deservedly hallowed Air Force abbreviation. He had not smiled at his mother’s use of the term because what she was telling him was vaguely troubling. The last image in his mind, prior to the appearance of her face, was of the coppery blur of the rotors in the omnibus. That blur had seemed to enfold and annihilate him. When could Kaprow, or anyone else, have tried to talk to him since the dream of his deliverance?

“Lie back, Johnny, just lie back. They lost you for a month, were afraid they wouldn’t be able to retrieve you at all. I think Kaprow finally brought pressure to bear on the authorities to let me come see you when you failed to respond to either the doctors or him. You were like a zombie, he said. Thought the sight of a familiar face might jolt you back to reality. Here I am, then. A shot of Old Jolt, Johnny. Am I working?

I think I am, I can tell by your eyes…. This reminds me of when you were little. Didn’t speak a word until you were almost two. Said ‘cao’ in Richardson’s pasture on the outskirts of that new housing area in Van Luna. You had the most expressive eyes, though. You could talk with them as well as some people can with words. You haven’t lost any of that ability, either. I can see by your eyes that this shot of Old Jolt has gone right to your head.”

“Right,” he echoed her, smiling.

“And that’s the prettiest word I’ve heard you say since your first really emphatic ‘ cao ,’ I swear to God it is, John-John.” She turned her head away, refused to look at him. “Yesterday was my birthday. I told them you’d wake up for my birthday. You’re only a day late, and it’s a fine, fine present.” She looked at him again. “I’m fifty, can you believe that? Half a goddamn century. I feel like Methuselah’s mother.”

He worked to get the words out: “I’m Methuselah, then.”

“You all right?”

“Think so.”

“Don’t talk. Don’t try to get up. You’re going to have a raft of visitors once they know you’re conscious and able to talk.”

He lay back in the stiff sheets and found that he was clad in a hospital gown, a gray sheath like a wraparound bib. His leg ached dully, and the antiseptic tang of the room offended his nostrils, worked its way into his throat like a hook. When he was very small, Jeannette had once let him take a whiff from an ammonia bottle and he had screamed as if she had gassed him. The smell in this room, he realized, was equally offensive. Water came to his eyes, flushed from his tear ducts by the stinging smell of disinfectants, rubbing alcohol, arcane medicines.

Читать дальше

![Ally Carter - [Gallagher Girls 01] I'd Tell You I Love You But Then I'd Have to Kill You](/books/262179/ally-carter-gallagher-girls-01-i-d-tell-you-i-lo-thumb.webp)