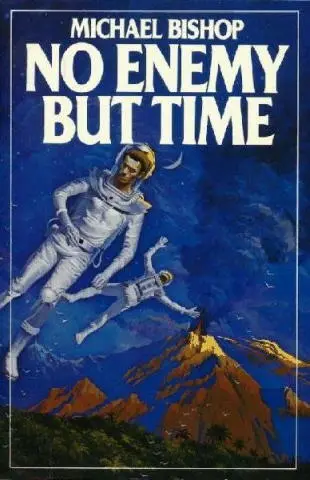

Michael Bishop

NO ENEMY BUT TIME

To Floyd J. Lasley, Jr., Our mild Irish Godfather

Ashe has on other book-length projects, my editor, David Hartwell, worked very closely with me on the final version of this manuscript. I wish to thank both him and his family for boarding me over the three-day period that he and I devoted to an especially intense scrutiny of my work.

I also owe a great deal to my wife, Jeri Bishop, for her support, encouragement, and suggestions—during both the protracted research that this novel entailed and the many months of actual writing.

No Enemy But Time is a work of fiction. The country Zarakal does not exist on any map, but I imagine its geographic dimensions roughly coextensive with those of Kenya. However, the reader may not automatically suppose that Zarakal and Kenya are historically, sociologically, and politically identical.

They are not, nor were they intended to be.

Likewise, the protohuman hominid that my characters refer to as Homo zarakalensis is a fictional construct. I have created this spurious ancestral human as a means to a particular dramatic and narrative end.

For the most part, however, my paleoanthropological nomenclature conforms to the usage of those scientists currently struggling to solve the riddle of human origins. Although I urge readers not to regard this work as a textbook on hominid evolution, I have not deliberately misconstrued the enormous amounts of data available to those fascinated by the topic.

Debates about classifications and interpretations will undoubtedly continue to rage. A decade from now, possibly even less, the terms designating Homo habilis and Australopithecus afarensis may be taxonomic fossils—just as the bones they are intended to identify are virtually all that remain of the small, bipedal creatures who pioneered the frontiers of our humanity so many million years ago.

—Michael Bishop Pine Mountain, Georgia June 23, 1981

Prologue

“Next Slide, Please”

I time-traveled in spirit long before I did so in bodily fact. Until the moment of my departure, you see, my life had been a slide show of dreams divided one from another by many small darknesses of wakeful dread and anticipation. Sometimes the dreams and the darknesses alternated so rapidly that I was unable to tell them apart. An inability to distinguish between waking and dreaming may be an index of madness, or it may be a gift. After more than thirty years of trying to integrate the two into a coherent pattern, I understand that it is, or was, my gift.

When I was four, my father Hugo brought home a slide projector from the BX at McConnell Air Force Base in Wichita, Kansas. This was a machine with a circular tray for the slides, and if you kept clicking the changer, eventually the same scenes—the same past moments—would flash into fleeting prominence over and over again. In a way, then, each slide wheel was a time machine; and the procession of images on either the wall or the hanging linen sheet was a cyclical tour of bygone days.

To me, though, it was often more fun to have gaps in the tour, empty tray slots that translated into windows of blinding white illumination—for my father, who spoke English with a noticeable Spanish accent, liked to make up silly captions for those vacant squares:

“Moby Deek’s backside!”

“Frosty the Snowman at a Koo Kloox Klan rally!”

“A polar bear swimmin’ in a vat of vanilla ice cream!”

My sister Anna and I would shout out captions of our own, most of them even more juvenile than Hugo’s, and our mother Jeannette, who appreciated continuity, would urge him to get on with the show.

She tried to keep the circular trays filled with slides—each one held a hundred—so that there would be relatively few occasions for nonsense. It was not that she lacked a sense of humor, but that for her the wheel of slides represented a living world, a mandala of bright, recapturable experience. Her fun lay in reexperiencing each brilliant epiphany in the show.

After Hugo was transferred from McConnell to Francis E. Warren AFB in Cheyenne, Wyoming, and after Jeannette went to work for one of Cheyenne’s daily newspapers as a book columnist and feature writer, our family took fewer photographs. The slide trays still came out on birthdays, holidays, and Jeannette’s occasional moments of nostalgia—but once you had endured the programs four or five times, they were as predictable as television situation comedies. “John-John Pointing at Cows” always preceded “Jeannette Hauling John-John Out of Pasture” and always followed “John-John Bundled for October Walk.” You could count on this sequence.

From the fleeting darknesses between changer clicks, I began to create my own private “slides.” In fact, after my eighth birthday, I usually fell into a light trance whenever the projection equipment was operating; I dropped out of the here-and-now into a past even older than the one flashing by on the wall.

Already I was notorious within my family as a dreamer—not the spaced-out, chin-on-fist variety common to most classrooms, but a rare, visionary kind of dreamer—and I am now convinced that Jeannette’s apparent fondness for our slide programs was in part a function of her well-meaning desire to tie me to reality. She wanted to reinforce my allegiance to the Monegal family by impressing upon me the indelibility, the vividness, of my tenure among the three of them.

Each slide wheel, as I have said, was a time machine (a time machine with a comfortably circumscribed range), but it was also a yoke to the status quo. By ignoring the Monegal Family Past and investing each moment of darkness between the slides with a freight of private meaning, I was subverting my mother’s intentions. I was distancing myself emotionally as well as temporally.

When I was ten, I played a joke that in some ways foreshadowed the principal rebellion of my adolescence.

Hugo, a noncommissioned minion of the Strategic Air Command, had just been sent from Cheyenne to Guam. Even though there were facilities for dependents on the island, he had gone unaccompanied—not only to decrease the length of his tour, but to honor the demands of Anna (who was happy at her current school) and Jeannette (who had begun to earn a respectable paycheck from her reviewing and feature writing). That no one had consulted me about my stake in the matter was no big deal because my dreams were the same wherever I happened to be. I was trying to learn more about them, though, primarily by going to the library and poring over magazines devoted to either travel or natural history. With Hugo absent, in fact, the three of us still in Cheyenne seemed to be riding a dozen centrifugal interests outward from the nuclear heart of the family.

My joke? Well, right before Christmas that year I went to the closet where we kept our slide equipment and removed the boxes containing the trays. Back in my room I spent a good thirty minutes randomly rearranging slides, leaving gaps in the sequence and slotting several transparencies sideways or upside-down. “John-John Bundled for October Walk” ended up following a topsy-turvy “Jeannette Enjoying Beach at Cádiz,” while “Anna Watching Semana Santa Procession in Seville” gave way to a sideways-slotted “Grandfather Rivenbark Checking Out Customers at Old Van Luna Grocery.” Then I returned the trays to their boxes and the boxes to their closet shelves.

On Christmas Eve Jeannette told Anna to fetch the slides and set up for another trip into the Monegal Family Past. Anna, now fourteen, obeyed, and we gathered in the dining room. I turned off the lights, Anna clicked her magic changer, and a kind of wacky chaos ensued.

Читать дальше

![Ally Carter - [Gallagher Girls 01] I'd Tell You I Love You But Then I'd Have to Kill You](/books/262179/ally-carter-gallagher-girls-01-i-d-tell-you-i-lo-thumb.webp)