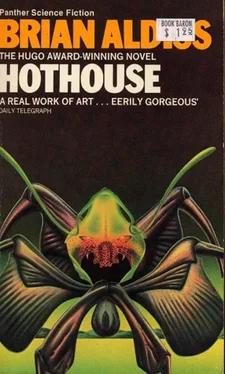

Brian Aldiss - Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Brian Aldiss - Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

, Hugo Best Short Story Winner of 1962, we are transported millions of years from now, to the boughs of a colossal banyan tree that covers one face of the globe. The last remnants of humanity are fighting for survival, terrorised by the carnivorous plants and the grotesque insect life.

Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

'Keep away.'

Laren sent out an irritable wail.

'Give me the baby,' Gren said again.

'You are not yourself. I'm frightened of you, Gren. Sit down again!, Stay away! Stay away!'

Still he came forward in a curiously slack way as if his nervous system was having to respond to two rival centres of control. She raised her knife, but he took absolutely no notice of it. In his eyes hung a blind look like a curtain.

At the last moment, Yattmur broke. Dropping her knife, she turned and sprinted from the cave, clutching her baby tightly.

Thunder came tumbling down the hill at her. Lightning sizzled, striking one strand of a great traverser web that stretched from nearby up into the clouds. The strand spluttered and flared until rain quenched it. Yattmur ran, making for the cave of the tummy-bellies, not daring to glance back.

Only when she reached it did she realize how unsure she was of her reception. By then it was too late to hesitate. As she burst in out of the rain, tummy-bellies and mountainears jumped up to meet her.

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

GREN sank to his hands and knees among the painful stones at the mouth of the cave.

Complete chaos had overtaken his impressions of the external world. Pictures rose like steam, twisting in his inner mind. He saw a wall of tiny cells, sticky like a honeycomb, growing all about him. Though he had a thousand hands, they did not push down the wall; they came away thick with syrup that bogged his movements. Now the wall of cells loomed above his head, closing in. Only one gap in it remained. Staring through it, he saw tiny figures miles distant. One was Yattmur, down on her knees, gesticulating, crying because he could not get to her. Other figures he made out to be the tummy-bellies. Another he recognised as Lily-yo, the leader of the old group. And another – that writhing creature! – he recognized as himself, shut out from his own citadel.

The mirage fogged over and vanished.

Miserably, he fell back against the wall, and the cells of the wall began popping open like wombs, oozing poisonous things.

The poisonous things became mouths, lustrous brown mouths that excreted syllables. They impinged on him with the voice of the morel. They came so thickly on him from all sides that for a while it was only their shock and not their meaning that struck him. He screamed creakingly, until he realized the morel was speaking not with cruelty but regret; whereupon he tried to control his shivering and listen to what was being said.

'There were no creatures like you in the thickets of Nomans-land where my kind live,' the morel pronounced. 'Our role was to live off the simple vegetable creatures there. They existed without brain; we were their brains. With you it has been different. In the extraordinary ancestral compost heap of your unconscious mind, I have burrowed too long.

'I have seen so much to amaze me in you that I forgot what I should have been about. You have captured me, Gren, as surely as I have captured you.

'Yet the time has come when I must remember my true nature. I have fed on your life to feed my own; that is my function, my only way. Now I reach a point of crisis, for I am ripe.'

'I don't understand,' Gren said dully.

'A decision lies before me. I am soon to divide and sporulate; that is the system by which I reproduce, and I have little control over it. This I could do here, hoping that my progeny would survive somehow on this bleak mountain against rain and ice and snow. Or... I could transfer to a fresh host.'

'Not to my baby.'

'Why not to your baby? Laren is the only choice for me. He is young and fresh; he will be far easier to control than you are. True, he is weak as yet, but Yattmur and you will look after him until he becomes able to look after himself.'

'Not if it means looking after you as well.'

Before Gren finished speaking he received a blow, scattering directly over his brain, that sent him huddling against the cave wall in pain.

'You and Yattmur will not desert the baby under any circumstances. You know that, and I see it in your thought. You know also that if any opportunity came you would get away from these barren miserable slopes to the fertile lands of light. That also fits in with my plan. Time presses, man; I must move according to my needs.

'Knowing every fibre of you as I do, I pity your pain – but it can mean nothing at all to me when set against my own nature. I must have an able and preferably witless host that will carry me rapidly back into the sunlit world, so that I can seed there. So I have chosen Laren. That would be the best course for my progeny, don't you think?'

'I'm dying,' Gren moaned.

'Not yet,' twanged the morel.

At the back of the tummy-belly cave sat Yattmur, half-asleep. The foetid air of the place, the yammer of voices, the noise of the rain outside, all combined to dull her senses. She dozed, and Laren slept on a pile of dead foliage beside her. They had all eaten scorched leatherfeather, half-cooked, half-burnt over a blazing fire. Even the baby had accepted tit-bits.

When she appeared distraught at the cave entrance, the tummy-bellies welcomed her in, crying 'Come, lovely sandwich lady, out of the raining wetness where the clouds fall. Come in with us to cuddle and make warmth without water.'

'Who are these others with you?' She looked anxiously at the eight mountainears, who were grinning and jumping up and down at the sight of her.

Seen close to, they were very formidable: a head taller than the humans, with thick shoulders on which long fur stood out like a mantle. They had grouped together behind the tummy-bellies, but now began circling Yattmur, showing their teeth and calling to each other in a weird perversion of speech.

Their faces were the most fearsome Yattmur had ever seen. Long-jawed, low-browed, they had snouts and brief yellow beards, while their ears curled out of fuzzy short fur like segments of raw flesh. Quick and irritable in movement, they seemed never to leave their faces in repose: bars of long, sharp ivories appeared and disappeared behind grey lips as they snapped out questions at her.

'You yap you live here? On the Big Slope you yakker-yakker live? With the tummy-bellies, with the tummy-bellies live? You and them together, yipper-yap, slap-sleeping running living loving on the Big Big Slope?'

One of the largest mountainears asked Yattmur this rapid fire of questions, jumping before her and grimacing as he did so. His voice was so coarse and gutteral, his phrases so chopped into barks, that she had difficulty in understanding him at all. 'Yipper yapper yes live you on Big Black Slope?'

'Yes, I live on this mountain,' she said, standing her ground. 'Where do you live? What people are you?'

For answer he opened his goat eyes at her until a red brink of gristle showed all round them. Then he closed them tight, opened his cavernous jaws and emitted a high clucking soprano chord of laughter.

"These sharp-fur people are gods, lovely sharp gods, sandwich lady,' the tummy-bellies explained, the three of them hopping before her, jostling each other in an agony to be first to unburden their souls to her. 'These sharp-fur people are called sharp-furs. They are our gods, missis, for they run all over the Big Slope mountain, to be gods for dear old tummy-belly men. They are gods, gods, they are big fierce gods, sandwich lady. They have tails!

This last sentence was delivered in a cry of triumph. The whole mob of them went streaming round the cave, shrieking and whooping. Indeed the sharp-furs had tails, sticking out of their rumps at impudent angles. These the tummy-bellies chased, trying to pull and kiss them. As Yattmur shrank back, Laren, who had watched this rout for a moment wide-eyed, began to bawl at the top of his voice. The dancing figures imitated him, interposing shouts and chants of their own.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.