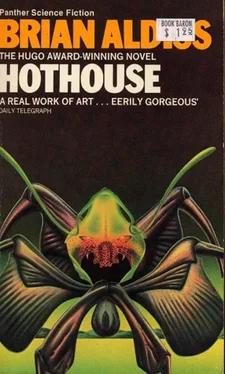

Brian Aldiss - Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Brian Aldiss - Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

, Hugo Best Short Story Winner of 1962, we are transported millions of years from now, to the boughs of a colossal banyan tree that covers one face of the globe. The last remnants of humanity are fighting for survival, terrorised by the carnivorous plants and the grotesque insect life.

Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Suddenly, frayed by the countless miles of travel and subverted by wet, its joints reached breaking point and split. The stalker's six legs fell outwards, its body dropped to the muddy ground. As it hit, the six drums that comprised it burst, scattering notchy seeds all about.

This sodden ruin in the middle of snow was at once the end and the beginning of the stalker plant's journey. Forced like all plants to solve the terrible problem of overcrowding in a hothouse world, it had done so by venturing into those chilly realms beyond the timberline where the jungle could not grow. On this slope, and a few similar ones within the twilight zone, the stalkers played out one phase of their unending cycle of life. Many of the seeds dispersed now would germinate, where they had plenty of space and some warmth, growing into the hardy little crawlpaws; and some of those crawlpaws, triumphing over a thousand obstacles, would eventually find their way to the realms of true warmth and light, there to root and flower and continue the endless vegetable mode of being.

When the seed drums split, the humans were flung aside into mud. Painfully they stood up, their limbs creaking with stiffness. So thickly swirled the snow and cloud about them that they could hardly see each other: their bodies became white pillars, illusory.

Yattmur was anxious to gather the tummy-belly men together before they became lost. Seeing a figure glistening in the thick dim light, she ran to it and grasped it. A face turned snarling towards her, yellow teeth and hot eyes flared into her face. She cowered from attack, but the creature was gone in a bound.

This was their first intimation that they were not alone on the mountain.

'Yattmur!' Gren called. 'The tummy-bellies are here. Where are you?'

She went running to him, her stiffness forgotten in fright.

'Something else is here,' she said. 'A white creature, wild and with teeth and big ears!'

The three tummy-bellies set up a cry to the spirits of death and darkness as Yattmur and Gren stared about.

'In this filthy mess, it's impossible to see anywhere,' Gren said, dashing snow from his face.

They stood huddled together, knives ready. The snow slackened abruptly, turned to rain, cut off. Through the last shower they saw a line of a dozen white creatures bounding over a brow of the mountain towards the dark side. Behind them they pulled a sort of sledge loaded with sacks, from one of which a trail of stalker seeds bounced.

A ray of sun pierced across the melancholy hillsides. As if they feared it, the white creatures hurried into a pass and disappeared from view.

Gren and Yattmur looked at each other.

'Were they human?' Gren asked.

She shrugged. She did not know. She did not know what human meant. The tummy-bellies, now lying in the mud and groaning: were they human? And Gren, so impenetrable now that it seemed as if the morel had taken him over: could it be said he was still human?

So many riddles, some she could not even formulate in words, never mind answer... But once more the sun shone warm on her limbs. The sky was lined with crumpled lead and gilt. Above them on the mountain were caves. They could go there and build a fire. They could survive and sleep warmly again...

Brushing her hair off her face, she began to walk slowly uphill. Although she felt heavy and troubled, she knew enough to know that the others would follow her.

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

LIFE on the big slope was endurable, and sometimes more than just endurable, for the human spirit has a genius for making mountains out of molehills of happiness.

In the great and awful landscape in which they found themselves, the humans were dwarfed almost to insignificance. The pastoral of Earth and the drama of the weather unrolled without taking cognisance of them. Between slope and cloud, amid mud and snow, they lived their humble lives.

Though night and day no longer marked the passage of time, there were other incidents to tell of its passing. The storms increased, while the temperature fell; sometimes the rain that fell was icy; sometimes it was scalding hot, so that they ran screaming for the shelter of their caves.

Gren became more morose as the morel took a firmer hold over his will. Aware of how its own cleverness had brought them to a dead end, it brooded increasingly; oppressed by its need to procreate, it cut Gren off from communication with his fellows.

A third event marked the unceasing progression of time. During a storm, Yattmur gave birth to a son.

It became the reason for her existence. She called it Laren and was content.

On a remote mountainside of Earth, Yattmur cradled her baby in her arms, singing to him though he slept.

The upper slopes of the mountain were bathed in the rays of the ever-setting sun, while the lower slopes were lost in night. This whole tumbled area was one of darkness, lit occasionally by ruddy beacons where mountains thrust themselves up in stony imitation of living things to reach the light.

Even where darkness lay thickest, it was not absolute. Just as death is not absolute – the chemicals of life later reforming to create more life – so the darkness was often to be reckoned merely a lesser degree of light, a realm where lurked creatures that had been forced out of the brighter and more populous regions.

Among these exiles were the leather-feathers, a pair of which skimmed over the mother's head, enjoying an acrobatic flight, storming downwards with their wings closed or spreading them to float upwards on a current of warmer air. The baby awoke and the mother pointed the flying creatures out to him.

'There they go, Laren, wheeee, down into the valley and -look, there they are! – back into the sun again, up so high.'

Her baby wrinkled its nose, indulging her. The leathery fliers dived and turned, flashing in the light before they sank into a mesh of shadows, only to rise again, as if out of a sea, sweeping upwards occasionally almost as far as the low canopy of cloud. The clouds held a bronze aura; they were as much a feature of the landscape as the mountains themselves, reflecting light over the obscure world below, scattering it from their contours like showers, until the barren countrysides were dappled with yellow and fugitive gold.

Amid this cross-hatching of brightness and dusk the leather-feathers sped, feeding on the spores which even here floated thick, wafted from the vast propagating machine that covered the sunlit face of the planet. The infant Laren gurgled in delight, stretching out his hands; Yattmur the mother gurgled too, filled with pleasure at every movement of her child.

One of the fliers was diving steeply now. Yattmur watched with sudden surprise, noticing its lack of control. The leather-feather twisted down, its mate winking powerfully after it. Just for a moment she thought it was going to straighten: then it struck the mountainside with an audible thwack!

Yattmur stood up. She could see the leatherfeather, a motionless heap above which the bereft mate fluttered.

She was not the only one who had observed the fatal dive. Farther over on the big slope, one of the tummy-belly men began running towards the fallen bird, crying to his two companions as he went. She heard the words, 'Come and look see with eyes the fallen birds of wings!' clear in the clear air, she heard the sound of his feet thudding on the ground as he trotted down the slope. Mother-like, she stood watching, clasping Laren and regretting any incident that disturbed her peace.

Something else was after the fallen bird. Yattmur glimpsed a group of figures farther down the hill, coming rapidly from behind a spur of stone. Eight of them she counted, white-clad figures with pointed noses and large ears, outlined sharply against the deep blue gloom of a valley. They dragged a sleigh behind them.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.