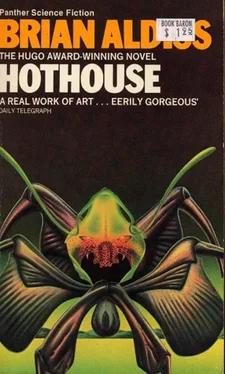

Brian Aldiss - Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Brian Aldiss - Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

, Hugo Best Short Story Winner of 1962, we are transported millions of years from now, to the boughs of a colossal banyan tree that covers one face of the globe. The last remnants of humanity are fighting for survival, terrorised by the carnivorous plants and the grotesque insect life.

Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The stalker over to their left was also in trouble. Though they could see it only dimly, it had walked into a stretch where the worms grew taller. Silhouetted against a bright strip of land to the far side of the hill, it had been reduced to immobility, while a forest of boneless fingers boiled all round it. It toppled. Without a sound it fell, the end of its long journey marked by worms.

Unaffected by the catastrophe, the stalker on which the humans rode continued to edge downwards.

Already it was through the thickest patch of opposition. The worms were rooted to the ground and could not follow. They fell away, grew shorter, more widely spaced, finally sprouted only in bunches, which the stalker avoided.

Relaxing slightly, Gren took the opportunity to look more searchingly at their surroundings. Yattmur hid her face in his shoulder; sickness stirred in her stomach and she wanted to see no more.

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

ROCK and stones lay thick on the ground below the stalker's legs. This detritus had been shed by an ancient river which no longer flowed; the old river bed marked the bottom of a valley; when they crossed it, they began to climb, over ground free of any form of growth.

'Let us die!' moaned one of the tummy-belly men. 'It is too awful to be alive in the land of death. Turn all things the same, great herder, give us the benefit of the cutting of your cosy and cruel little cutting sword. Let tummy-belly men have a quick short cutting to leave this long land of death! O, O, O, the cold burns us, ayeee, the long cold cold!'

In chorus they cried their woe.

Gren let them moan. At last, growing weary of their noise, which echoed so strangely across the valley, he lifted his stick to strike them. Yattmur restrained him.

'Are they not right to moan?' she asked. 'I would rather moan with them than strike them, for soon it must be that we shall die with them. We have gone beyond the world, Gren. Only death can live here.'

'We may not be free, but the stalkers are free. They would not walk to their death. You are turning into a tummy-belly, woman!'

For a moment she was silent. Then she said, 'I need comfort, not reproach. Sickness stirs like death in my stomach.'

She spoke without knowing that the sickness in her stomach was not death but life.

Gren made no answer. The stalker moved steadily over rising ground. Lulled by the threnody of the tummy-bellies, Yattmur fell asleep. Once the cold woke her. The chant had ceased; all her companions were sleeping. A second time she woke, to hear Gren weeping; but lethargy had her, so that she succumbed again to tiring dreams.

When she roused once more, she came fully awake with a start. The dreary twilight was broken by a shapeless red mass apparently suspended in the air. Gasping between fright and hope, she shook Gren.

'Look, Gren,' she cried, pointing up ahead. 'Something burns there! What are we coming to?'

The stalker quickened its pace, almost as if it had scented its destination.

In the near-dark, seeing ahead was baffling. They had to stare for a long while before they could make out what lay in front of them. A ridge stretched immediately above them; as the stalker made its way up to the ridge, they saw more and more of what it had hitherto obscured. Some way behind the ridge loomed a mountain with a triple peak. It was this mountain that glowed so redly.

They gained the ridge, the stalker hauled itself stiffly over the lip, and the mountain was in full view.

No sight could have been more splendid.

All about, night or a pale brother of night reigned supreme. Nothing stirred; only the chilly breeze moved with stealth through the valleys unseen below them, like a stranger in a ruined town at midnight. If they were not beyond the world, as Yattmur thought, they were beyond the world of vegetation. Utter emptiness obscured utter darkness beneath their feet, magnifying their least whisper to a stammering shriek.

From all this desolation rose the mountain, high and sublime; its base was lost in blackness; its peaks soared tall enough to woo the sun, to fume in rosy warmth, to throw a reflection of that glow into the wide trough of obscurity at its foot.

Taking Yattmur's arm, Gren pointed silently. Other stalkers had crossed the darkness they had crossed; three of them could be seen steadily mounting the slopes ahead. Even their aloof and eerie figures mitigated the loneliness.

Yattmur woke the tummy-bellies, keen to let them see the prospect. The three plump creatures kept their arms round each other as they gazed up at the mountain.

'O the eyes make a good sight!' they gasped.

'Very good,' Yattmur agreed.

'O very good, sandwich lady! This big chunk of ripe day makes a hill of a hill shape to grow in this night-and-death place for us. It is a lovely sun slice for us to live in as a happy home.'

'Perhaps so,' she agreed, though already she foresaw difficulties beyond their simpler comprehensions.

They climbed. It grew lighter. Finally they emerged from the margin of shadow. The blessed sun shone on them again.

They drank the sight of it until their eyes were blinded and the sombre valleys beneath them danced with orange and green spots. Compressed to lemon shape and parboiled crimson by atmosphere, it simmered at them from the ragged lip of the world, its rays beating outwards over a panorama of shadow. Broken into a confusing array of searchlights by a score of peaks thrusting up from the blackness, the lowest strata of sunlight made a pattern of gilt wonderful to behold.

Unmoved by these vistas, the stalker continued immutably to climb, its legs creaking at every step. Beneath it scuttled an occasional crawlpaw, heading down towards the shrouded valley and ignoring their progress upward. At last the stalker came to a position almost in the dip between two of the three peaks. It halted.

'By the spirits!' Gren exclaimed. 'I think it means to carry us no farther.'

The tummy-bellies set up a hullabaloo of excitement, but Yattmur looked round doubtfully.

'How do we get down if the stalker is not going to sink as the morel said?' she asked.

'We must climb down,' Gren said, after some thought, when the stalker showed no further sign of moving.

'Let me see you climb down first. With the cold, and with crouching here too long, my limbs are as stiff as sticks.'

Looking defiantly at her, Gren stood up and stretched himself. He surveyed the situation. Since they had no rope, they had no means of getting down. The smoothly bulging skins of the seed drums prevented the possibility of their climbing down on to the stalker's legs. Gren sat again, lapsing into blackness.

'The morel advises us to wait," he said. He put an arm about Yattmur's shoulders, ashamed of his own helplessness.

There they waited. There they ate a morsel more of their food, which had begun to sprout mould. There they had perforce to fall asleep; and when they woke the scene had changed hardly at all, except that a few more stalkers now stood silent farther down the slopes, and that thick clouds were drawing across the sky.

Helpless, the humans lay there while nature continued inflexibly to work about them, like a huge machine in which they were the most idle cog.

The clouds came rumbling up from behind the mountain, big and black and pompous. They curdled through the passes, turning to sour milk where the sun lit them. Presently they obscured the sun. The whole mountainside was swallowed. It began to snow sluggish wet flakes like sick kisses.

Five humans burrowed together, turning their backs upwards to the drift. Underneath them, the stalker trembled.

Soon this trembling turned to a steady sway. The stalker's legs sank a little into the moistened ground; then, as they too became softened by wet, they began to buckle. The stalker became increasingly bow-legged. In the mists of the mountainside, other stalkers – lacking the assistance of weight on top of them – began slowly to copy it. Now the legs quivered farther and farther apart; its body sank lower.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.