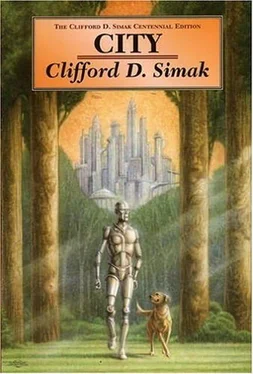

Clifford Simak - City

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Clifford Simak - City» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:City

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

City: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «City»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

City — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «City», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"You are helping someone else?"

Andrew shook his head. "Some of us get a call... a call to go and work there. The rest of us do not try to stop them, for we are all free agents."

"But who is building it?" asked Homer.

"The ants," said Andrew.

Homer's jaw dropped slack.

"Ants? You mean the insects. The little things that live in ant hills?"

"Precisely," said Andrew. He made the fingers of one hand run across the sand like a harried ant.

"But they couldn't build a place like that," protested Homer. "They are stupid."

"Not any more," said Andrew.

Homer sat stock still, frozen to the sand, felt chilly feet of terror run along his nerves.

"Not any more," said Andrew, talking to himself. "Not stupid any more. You see once upon a time, there was a man named Joe..."

"A man? What's that?" asked Homer.

The robot made a clucking noise, as if gently chiding Homer.

"Men were animals," he said. "Animals that went on two legs. They looked very much like us except they were flesh and we are metal."

"You must mean the websters," said Homer. "We know about things like that, but we call them websters."

The robot nodded slowly; "Yes, the websters could be men. There was a family of them by that name. Lived just across the river."

"There's a place called Webster House," said Homer. "It stands on Webster's Hill."

"That's the place," said Andrew.

"We keep it up," said Homer. "It's a shrine to us, but we don't understand just why. It is the word that has been passed down to us... we must keep Webster House."

"The websters," Andrew told him, "were the ones that taught you Dogs to speak."

Homer stiffened. "No one taught us to speak. We taught ourselves. We developed in the course of many years. And we taught the other animals."

Andrew, the robot, sat hunched in the sun, nodding his bead as if be might be thinking to himself.

"Ten thousand years," he said. "No, I guess it's nearer twelve. Around eleven, maybe."

Homer waited and as he waited he sensed the weight of years that pressed against the hills, the years of river and of sun, of sand and wind and sky.

And the years of Andrew.

"You are old," be said. "You can remember that far back?"

"Yes," said Andrew. "Although I am one of the last of the man-made robots, I was made just a few years before they went to Jupiter."

Homer sat silently, tumult stirring in his brain.

Man... a new word.

An animal that went on two legs.

An animal that made the robots, that taught the Dogs to talk.

And, as if he might be reading Homer's mind, Andrew spoke to him.

"You should not have stayed away from us," he said. "We should have worked together. We worked together once. We both would have gained if we had worked together."

"We were afraid of you," said Homer. "I am still afraid of you."

"Yes," said Andrew. "Yes, I suppose you would be. I suppose Jenkins kept you afraid of us. For Jenkins was a smart one. He knew that you must start fresh. He knew that you must not carry the memory of Man as a dead weight on your necks."

Homer sat silently.

"And we," the robot said, "are nothing more than the memory of Man. We do the things he did, although more scientifically, for, since we are machines, we must be scientific. More patiently than Man, because we have forever, and he had a few short years."

Andrew drew two lines in the sand, crossed them with two other lines. He made an X in the open square in the upper left hand corner.

"You think I'm crazy," he said. "You think I'm talking through my hat."

Homer wriggled his haunches deeper into the sand.

"I don't know what to think," he said. "All these years..."

Andrew drew an O with his finger in the centre square of the cross-hatch he had drawn in the sand.

"I know," he said. "All these years you have lived with a dream. The idea that the Dogs were the prime movers. And the facts are hard to understand, hard to reconcile. Maybe it would be just as well if you forgot what I said. Facts are painful things at times. A robot has to work with them, for they are the only things he has to work with. We can't dream, you know. Facts are all we have."

"We passed fact long ago," Homer told him. "Not that we don't use it, for there are times we do. But we work in other ways. Intuition and cobblying and listening."

"You aren't mechanical," said Andrew. "For you, two and two are not always four, but for us it must be four. And sometimes I wonder if tradition doesn't blind us. I wonder sometimes if two and two may not be something more or less than four."

They squatted in silence, watching the river, a flood of molten silver tumbling down a coloured land.

Andrew made an X in the upper right hand corner of the cross-hatch, an O in the centre upper space, and X in the centre lower space. With the flat of his hand, he rubbed the sand smooth.

"I never win," he said. "I'm too smart for myself."

"You were telling me about the ants," said Homer. "About them not being stupid any more."

"Oh, yes," said Andrew. "I was telling you about a man named Joe..."

Jenkins strode across the hill and did not look to either left or right, for there were things he did not wish to see, things that struck too deeply into memory. There was a tree that stood where another tree had stood in another world.

There was the lay of ground that had been imprinted on his brain with a billion footsteps across ten thousand years.

The weak winter sun of afternoon flickered in the sky, flickered like a candle guttering in the wind, and when it steadied and there was no flicker it was moonlight and not sunlight at all.

Jenkins checked his stride and swung around and the house was there... low-set against the ground, sprawled across the hill, like a sleepy young thing that clung close to mother earth.

Jenkins took a hesitant step and as he moved his metal body glowed and sparkled in the moonlight that had been sunlight a short heartbeat ago.

From the river valley came the sound of a night bird crying and a raccoon was whimpering in a cornfield just below the ridge.

Jenkins took another step and prayed the house would stay although he knew it couldn't because it wasn't there.

For this was an empty hilltop that had never known a house. This was another world in which no house existed.

The house remained, dark and silent, no smoke from the chimneys, no light from the windows, but with remembered lines that one could not mistake.

Jenkins moved slowly, carefully, afraid the house would leave, afraid that he would startle it and it would disappear.

But the house stayed put. And there were other things. The tree at the corner had been an elm and now it was an oak, as it had been before. And it was autumn moon instead of winter sun. The breeze was blowing from the west and not out of the north.

Something happened, thought Jenkins. The thing that has been growing on me. The thing I felt and could not understand. An ability developing? Or a new sense finally reaching light? Or a power I never dreamed I had.

A power to walk between the worlds at will. A power to go anywhere I choose by the shortest route that the twisting lines of force and happenstance can conjure up for me.

He walked less carefully and the house still stayed, un-frightened, solid and substantial.

He crossed the grass-grown patio and stood before the door.

Hesitantly, he put out a hand and laid it on the latch. And the latch was there. No phantom thing, but substantial metal.

Slowly he lifted it and the door swung in and he stepped across the threshold.

After five thousand years, Jenkins had come home... back to Webster House.

So there was a man named Joe. Not a webster, but a man.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «City»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «City» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «City» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.