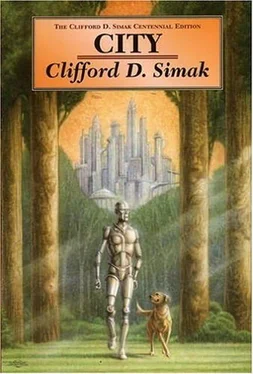

Clifford Simak - City

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Clifford Simak - City» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:City

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

City: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «City»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

City — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «City», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

We were the inheritors, we had been left the legacy, we were better off than any race had ever been or could hope to be again. And so we rationalized once more and we forgot about the glory of the race, for while it was a shining thing, it was a toilsome and humiliating concept.

" Jenkins," said Webster soberly, "we've wasted ten whole centuries."

"Not wasted, sir," said Jenkins. "Just resting, perhaps. But now, maybe, you can come out again. Come back to us."

"You want us?"

"The dogs need you," Jenkins told him. "And the robots, too. For both of them were never anything other than the servants of man. They are lost without you. The dogs are building a civilization, but it is building slowly."

"Perhaps a better civilization than we built ourselves," said Webster. "Perhaps a more successful one. For ours was not successful, Jenkins."

"A kinder one," Jenkins admitted, "but not too practical. A civilization based on the brotherhood of animals – on the psychic understanding and perhaps eventual communication and intercourse with interlocking worlds. A civilization of the mind and of understanding, but not too positive. No actual goals, limited mechanics – just a groping after truth, and the groping is in a direction that man passed by without a second glance."

"And you think that man could help?"

"Man could give leadership," said Jenkins.

"The right kind of leadership?"

"That is hard to answer."

Webster lay in the darkness, rubbed his suddenly sweating hands along the blankets that covered his body.

"Tell me the truth," he said and his words were grim. "Man could give leadership, you say. But man also could take over once again. Could discard the things the dogs are doing as impractical. Could round the robots up and use their mechanical ability in the old, old pattern. Both the dogs and robots would knuckle down to man."

"Of course," said Jenkins. "For they were servants once. But man is wise – man knows best."

"Thank you, Jenkins," said Webster. "Thank you very much."

He stared into the darkness and the truth was written there.

His track still lay across the floor and the smell of dust was a sharpness in the air. The radium bulb glowed above the panel and the switch and wheel and dials were waiting, waiting against the day when there would be need of them.

Webster stood in the doorway, smelling the dampness of the stone through the dusty bitterness.

Defence, he thought, staring at the switch. Defence – a thing to keep one out, a device to seal off a place against all the real or imagined weapons that a hypothetical enemy might bring to bear.

And undoubtedly the same defence that would keep an enemy out would keep the defended in. Not necessarily, of course, but

He strode across the room and stood before the switch and his hand went out and grasped it, moved it slowly, and knew that it would work.

Then his arm moved quickly and the switch shot home. From far below came a low, soft hissing as machines went into action. The dial needles flickered and stood out from the pins.

Webster touched the wheel with hesitant fingertips, stirred it on its shaft and the needles flickered again and crawled across the glass. With a swift, sure hand, Webster spun the wheel and the needles slammed against the farthest pins.

He turned abruptly on his heel, marched out of the vault, closed the door behind him, climbed the crumbling steps.

Now if it only works, he thought. If it only works. His feet quickened on the steps and the blood hammered in his head.

If it only works!

He remembered the hum of machines far below as he had slammed the switch. That meant that the defence mechanism – or at least part of it – still worked.

But even if it worked, would it do the trick? What if it kept the enemy out, but failed to keep men in?

What if When he reached the street, he saw that the sky had changed. A grey, metallic overcast had blotted out the sun and the city lay in twilight, only half relieved by the automatic street lights. A faint breeze wafted at his cheek.

The crinkly grey ash of the burned notes and the map that he had found still lay in the fireplace and Webster strode across the room, seized the poker, stirred the ashes viciously until there was no hint of what they once had been.

Gone, he thought. The last clue gone. Without the map, without the knowledge of the city that it had taken him twenty years to ferret out, no one would ever find that hidden room with the switch and wheel and dials beneath the single lamp.

No one would know exactly what had happened. And even one guessed, there'd be no way to make sure. And even if one were sure, there'd be nothing that could be done about it.

A thousand years before it would not have been that way. For in that day man, given the faintest hint, would have puzzled out any given problem.

But man had changed. He had lost the old knowledge and old skills. His mind had become a flaccid thing. He lived from one day to the next without any shining goal. But he still kept the old vices – the vices that had become virtues from his own viewpoint and raised him by his own bootstraps. He kept the unwavering belief that his was the only kind, the only life that mattered – the smug egoism that made him the self-appointed lord of all creation.

Running feet went past the house on the street outside and Webster swung away from the fireplace, faced the blind panes of the high and narrow windows.

I got them stirred up, he thought. Got them running now. Excited. Wondering what it's all about. For centuries they haven't stirred outside the city, but now that they can't get out they' re foaming at the mouth to do it.

His smile widened.

Maybe they'll be so stirred up, they'll do something about it. Rats in a trap will do some funny things – if they don't go crazy first.

And if they do get out – well, it's their right to do so. If they do get out, they've earned their right to take over once again. He crossed the room, stood in the doorway for a moment, staring at the painting that hung above the mantel. Awkwardly, he raised his hand to it, a fumbling salute, a haggard goodbye. Then he let himself out into the street and climbed the hill – the route that Sara had walked only days before. The Temple robots were kind and considerate, soft-footed and dignified. They took him to the place where Sara lay and showed him the next compartment that she had reserved for him.

"You will want to choose a dream," said the spokesman of the robots. "We can show you many samples. We can blend them to your taste. We can-"

"Thank you," said Webster. "I do not want a dream." The robot nodded, understanding. "I see, sir. You only want to wait, to pass away the time."

"Yes," said Webster. "I guess you'd call it that."

"For about how long?"

"How long?"

"Yes. How long do you want to wait?"

"Oh, I see," said Webster. "How about forever?"

"Forever!"

"Forever is the word, I think," said Webster. "I might have said eternity, but it doesn't make much difference. There is no use of quibbling over two words that mean about the same."

"Yes, sir," said the robot.

No use of quibbling. No, of course, there wasn't. For he couldn't take the chance. He could have said a thousand years, but then he might have relented and gone down and flipped the switch. And that was the one thing that must not happen. The dogs had to have their chance. Had to be left unhampered to try for success where the human race had failed. And so long as there was a human element they would not have that chance. For man would take over, would step in and spoil things, would laugh at the cobblies that talked behind a wall, would object to the taming and civilizing of the wild things of the earth. A new pattern – a new way of thought and life – a new approach to the age – old social problem. And it must not be tainted by the stale breath of man's thinking.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «City»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «City» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «City» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.