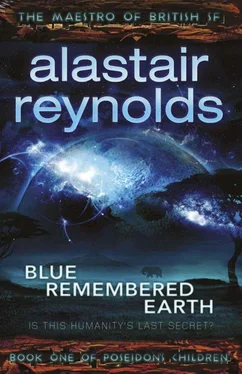

Alastair Reynolds

BLUE REMEMBERED EARTH

For Stephen Baxter and Paul McAuley: friends, colleagues and keepers of the flame.

“And I am dumb to tell a weather’s wind

How time has ticked a heaven round the stars.”

— Dylan Thomas

It is necessary to speak of beginnings. Understand one thing, though, above all else. Whatever brought us to this moment, this declaration, could never have had a single cause. If we have learned anything, it’s that life is never that simple, never that schematic.

You might say it was the moment when our grandmother set her mind to her last great deed. Or that it started when Ocular found something worthy of Arethusa’s attention, a smudge of puzzling detail on a planet circling another star, and Arethusa in turn felt honour bound to share that discovery with our grandmother.

Or that it was Hector and Lucas deciding that the family’s accounts could not tolerate a single loose end, no matter how inconsequential that detail might have looked at the time. Or the moment Geoffrey was called out of the sky, torn from his work with the elephants, drawn back to the household with the news that our grandmother was dead. Or his decision to confess everything to Sunday, and her choice that, rather than spurning her brother, she should take the path of forgiveness.

You might even say that it goes back to the moment in former Tanzania, a century and a half ago, when a baby named Eunice Akinya took her first raw breath. Or the moment that followed a heartbeat later, when she bellowed her first bawling cry, heralding a life of impatience. The world never moved quickly enough for our grandmother. She was always looking back over her shoulder, screaming at it to keep up, until the day it took her at her word.

Something made Eunice, though. She may have been born angry, but it was not until her mother cradled her under the stillness of a Serengeti night, beneath the cloudless spine of the Milky Way, that she began to grasp for what was forever out of reach.

All these stars, Eunice. All these tiny diamond lights. You can have them, if you want them badly enough. But first you must be patient, and then you must be wise.

And she was. So very patient and so very wise. But if her mother made Eunice, what shaped her mother? Soya was born two centuries ago, in a refugee camp, at a time when there were still famines and wars, droughts and genocides. What made her strong enough to gift this force of nature to the world, this child who became our grandmother?

We didn’t know it then, of course. If we considered her at all, it was mostly as a cold, forbidding figure none of us had ever touched or spoken to in person. Looking down on us from her cold Lunar orbit, isolated in her self-erected prison of metal and jungle, she seemed to belong to a different century. She had done great and glorious things – changed her world, left an indelible human mark on others – but those were deeds committed by a much younger woman, one with only a distant connection to our remote, peevish and disinterested grandmother. By the time we were born her brightest and best days were behind her.

So we thought.

Late May, after the long rains. The ground had borrowed moisture from the clouds; now the sky claimed its debt in endless hot, dry days. For the children, it was a relief. After weeks of bored confinement they were at last allowed to wander from the household, beyond the gardens and the outer walls, into the wild.

It was there that they came upon the death machine.

‘I still can’t hear anyone,’ Geoffrey said.

Sunday sighed and placed a hand on her brother’s shoulder. She was two years older than Geoffrey, and tall for her age. They stood on a rectangular rock, paces from the river that still ran fast and muddy.

‘There,’ she said. ‘Surely you can hear him now?’

Geoffrey kept a firm grip on the wooden aeroplane he was carrying.

‘I can’t,’ he said. He heard the river, the sighing of leaves in acacia trees, drowsy with the endless oven-like heat.

‘He’s in trouble,’ Sunday said determinedly. ‘We should find him, then tell Memphis.’

‘Maybe we should tell Memphis first, then look for him.’

‘And what if he drowns first?’

Geoffrey considered that unlikely. The waters had gone down compared to a week ago and the rains were petering out. Bilious clouds patrolled the horizon, thunder sometimes bellowed across the plains, but the sky was clear.

Besides, they had been this way many times. There were no homes here, no villages or towns. The trails they followed were trampled by elephants rather than people. And if by some chance Maasai were nearby, one of their boys would have known better than to get into difficulty.

‘Could it be the things in your head?’ Geoffrey asked.

‘I’m used to them now.’ Sunday hopped off the stone and pointed to the trees. ‘I think it’s coming from this way.’ She started walking, then turned back to Geoffrey. ‘You don’t have to come, if you’re scared.’

‘I’m not scared.’

Watchful for hazards, they crossed drying ground and boggy marshland. They wore snake-proof boots and long snake-proof trousers, short-sleeved shirts and wide-brimmed hats. Despite the mud they’d splashed around in, and the undergrowth they’d struggled through, their clothes remained as bright and colourful as when they’d put them on back at the household. More than could be said for Geoffrey’s mud-blotched arms, now crosshatched with fine, painful cuts from sharp-thorned bushes. Remembering a time when Memphis had praised him for not crying after tripping on the household’s hard marble floor, he had made a point of not telling his cuff to make the pain go away.

Sunday pushed confidently forward into the acacia trees, Geoffrey struggling to keep up. They passed the rusted white stump of an old windmill.

‘It’s not far now,’ Sunday called back, looking over her shoulder. The hat bounced jauntily against her back, secured by a drawstring around her neck. Geoffrey reached up to jam his own tighter, crunching it down on tight curls.

‘We’ll be safe, whatever happens,’ he said, as much to convince himself as anything else. ‘The Mechanism will be keeping an eye on us.’

He didn’t know what was on the other side of the trees. They had been here before, many times, but that didn’t mean they knew every bush, every rise and hollow of the landscape.

‘Something’s happened here!’ Sunday called, just out of sight. ‘The rain’s washed this whole slope away, like an avalanche! There’s something sticking out!’

‘Be careful,’ Geoffrey cried.

‘It’s some kind of machine,’ she shouted back. ‘I think the boy must be stuck inside.’

Geoffrey steeled himself and soldiered on. Trees fretted the sky with languidly moving branches, chips of kingfisher blue spangling through the gaps. Something slithered away under dry leaves a metre or two to his left. Thickening undergrowth clawed at his trousers, inflicting a rip. He stared in jaded wonderment as the two edges of torn fabric sutured themselves back together.

‘Here,’ Sunday said. ‘Come quickly, brother!’

He could see her now. They’d emerged at the edge of a bowl-shaped depression in the ground, hemmed in by dense stands of mixed trees. An arc of the bowl’s interior had collapsed away, leaving a steep rain-washed slope.

Something poked through the tawny ground. It was metal and as big as an airpod.

Geoffrey glanced up at the sky again.

‘What is it?’ he asked, although he had a dreadful sense that he already knew. He had seen something like this in one of his books. He recognised it by its many small wheels, too many of them along the visible side for this to be a car or truck. And the tracks that the wheels fitted into, with their hinged metal plates, one after the other like the segments of a worm.

Читать дальше