“What’s wrong?” I said pointlessly.

“My grandparents are dead. Aren’t they?”

“Yes they are.”

“And Clete. Clete is dead too.”

“Yes he is,” I said. I nodded, said slowly, “All of them are dead. You’re lucky to have survived. You were younger than they and stronger or it would have been you too.” I let her think about that for a while and said,

“They were old people. They wouldn’t have lived much longer anyway. You have your whole life in front of you; you couldn’t have stayed with them in the desert.”

“Yes I could.”

“All right,” I said. “Have it your way. You could have. Don’t you have any parents?”

“I have no one,” she said. “No one at all.”

“Neither do I,” I said. The way it came out I sounded almost cheerful, and this slash of morbidity—feeling that I could become closer to her because of the deaths, that is—was so sickening that for a moment I could not bear myself.

“You must be hungry,” I said, a reasonable way of changing the subject

“How about having some breakfast?”

“All right,” she said. She put her feet on the floor, came slowly but gracefully out of bed. Standing, she was closer to my height than I had realized, five seven or eight perhaps, and she carried herself with a dignity and grace that few women have. “Let’s go,” she said.

“Into the galley,” I said. I put out a hand instinctively, without even thinking about it, and she took it delicately. I led her from the room down a long hallway, equipment hanging from the ceiling in clumps like flowers: the wiring and network having the aspect of foliage. We could have been in a jungle, although, of course, we were not.

“Can I ask you a question?” she said, stopping.

I drew up gently, feeling her palm against mine. It would be partially inaccurate to say that simply holding her hand aroused me (and would make me appear some kind of a sexual lunatic as well), but I felt something very much like arousal, I would concede this. Call it an excess of tenderness. “By all means,” I said.

“What exactly are you doing here?”

“We’re doing a little research into statistical probabilities,” I said.

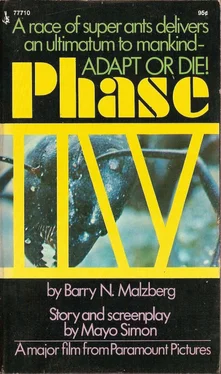

“Does it have to do with the ants?”

“I should say so,” I said. “I would say that the coefficient of correlation between the presence of ants and our own presence is close to point ninety… as you may be well aware.”

“No,” she said. “You don’t understand me. I know you’re here about the ants, the two of you that is. And he’s the one who killed my grandparents and Clete with his insecticide. But what do you do?”

“I’m the statistical part of the team,” I said. “He performs the experiments and I record them. He does the killing and I do the body count. Like that. Do you understand?”

She looked at me blankly. “I think so,” she said.

“Statisticians are famous for their peculiar relationship to fact. They both do and do not participate. But I want to be perfectly fair about this,”

I said judiciously. “Firing off the insecticide might have been his idea, but I hardly protested. In fact I cooperated willingly. The only thing I wouldn’t have done was to attack the towers.”

She started to walk again, pushing me gently. “I don’t think I understand a word you’re saying,” she said.

“That’s perfectly all right. Most people don’t.”

“But I guess that your work must be very interesting.”

“Oh, it is,” I said, leading her into the galley. “It’s fascinating.” There was barely enough space for the two of us in the little enclosure, but I only found the compression gratifying. Shoulder to shoulder with her, I opened a rack above and showed her the menu. “Powdered milk, powdered juice, powdered eggs, dehydrated bacon,” I said. “Just like home. But then again, what’s so great about home?”

“Are you in there, James?” Hubbs said from somewhere. We both jumped. “Come in here as soon as you’re finished, please. There are some things I want to show you.”

Kendra’s face was blank. “I’d better go,” I said.

“All right.”

“You can make yourself something.”

“If you say so.”

“Are you okay?” I said. I was propelled by something that I thought was anxiety but which I now understand was only a reluctance to leave her. I did not want to leave her. “If you’re not—”

She nodded. “I’m all right,” she said. “Why don’t you make yourself something to eat?”

“I’m not hungry.”

“James,” Hubbs said again. “We’ve got problems here; I’m afraid that you’d better come as soon as you can.”

She held that curious, intense look on me. “You’re afraid of him, aren’t you?” she said.

“Not exactly. But I am his assistant.”

“All right,” she said. “You’re not afraid of him.”

There was nothing else to say. She still looked at me levelly; she would have held that position indefinitely. I touched her on the shoulder gently and worked my way past her. Is it possible that I am afraid of Hubbs? The thought had never previously occurred to me, and it seems on the face of it to be ridiculous; we have the normal superior/assistant relationship, but I had never equated cooperation with fear. They are two entirely different things. Still, it is something worth considering. Is it possible that I have been intimidated all my life; that instinctively I place myself in a position of dependence to everyone with whom I work? Is it possible, for that matter, that I went into game theory simply because it gave me the illusion of control in a universe where even random factors would be plotted? All of these are chilling thoughts that may force me to rethink a number of assumptions, but there has simply been no time yet for such reflection, events overtaking us as they have. Still, it is interesting and frightening material. Do I identify with the ants, am I so immersed in this project now because unlike the products of individuating evolution the ants have neither a superior nor inferior relation to any of their fellows?

Does the gestalt fascinate me because a gestalt by definition makes no demands upon the discrete individual parts, enables them to flow into the overall pattern? I do not know. I simply do not know.

I left Kendra and went into the laboratory.

That unnatural brightness was flaring deep into Hubbs’s eyes, and he had contrived to wear his jacket in such a way that it completely obscured his arm from wrist to shoulder. “Look, James,” he said as Lesko came in, motioning with the unwounded arm through the window. “I may be entirely wrong about this, but we seem to be under a state of siege.”

Lesko’s gaze followed Hubbs’s arm. Outside in the sand, two small mounds about the size of a man’s head were pulsating on the desert. They were the color of mud, appeared to be at least partially liquefied, and it seemed to Lesko that there was an antlike expression on each of them… they seemed to hint at ants’ faces. Behind them, the gutted towers stood, their color now a dead white.

“Well, what the hell is that?” Lesko said.

“Well,” Hubbs said cheerfully, “it’s no optical illusion, my boy. It’s more than reflected sunlight. Our interior temperature is already up more than five degrees.”

“Good Lord,” Lesko said and noticed for the first time that it was indeed warm in the laboratory, warmer than it had ever been before. He verified this with a quick look at the wall thermometer, feeling sweat suddenly pool in his armpits.

“And there’s another interesting detail as well,” Hubbs said, motioning toward the mounds again. “How do you suppose the ants were able to build on a poison strip where they absolutely cannot live?” He struggled one-handed with the computer controls, his face flushed. “Think about that,” he said.

Читать дальше