Sten watched for a time. Then he turned away and went back into the house.

When Loren, breathless and satisfied, came into the kitchen to get coffee, something hot, some reward, he found Sten with a cold cup in front of him, his chin in his hands.

“You don’t, you know,” Loren said, “have to be best at everything. That’s not required.” As soon as he had said it, he regretted it bitterly. It was true, of course, but Loren had said it out of pride, out of success with Hawk, Sten’s bird. He wanted to go to Sten and put an arm around him, show him he understood, that he hadn’t meant what he said as crowing or triumph, just advice. And yet he had, too. And he knew that if he went to him, Sten would withdraw from him. That blond face, so whole and open and fine, could turn so black, so closed, so hateful. Loren made coffee, his exhilaration leaking away.

That night they turned away from the increasingly desperate government channels to watch “anything else,” Mika said; “something not real—” something they could contain within the compass of their dream of three. But the channels were all full of hectoring faces, or were inexplicably blank. Then they turned on a sudden, silent image and were held.

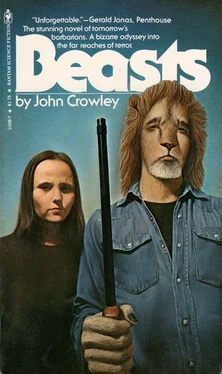

The leo, with his ancient gun under his arm, stood at the flapping tent door. His great head was calm, neither inquisitive nor self-conscious; if he was aware his portrait was being taken he didn’t show it. There was in his thick, roughly clothed body and blunt hands a huge repose, in his eyes a steady regard. Was it saintly or kingly he looked, or neither? The deep curl of his brow gave his eyes the easeful ferocity that the same curl gave to Hawk’s eyes: pitiless, without cruelty or guile. He only stood unmoving. There was no sound but that peculiar electronic note of solitude and loneliness, the intermittent boom of wind in an unshielded microphone.

“Well,” Mika said softly, “he’s not real.”

“Hush,” Sten said. A mild boyish voice was speaking without haste:

“He was captured at the end of the summer by rangers of the Mountain and agents of the Federal government. Since that time he has not been heard of.

The pride awaits word of him. They don’t speculate about whether he was murdered, as he might well have been, in secret; whether he’s imprisoned; whether he will ever return. For leos, there is no speculation, no fretting, no worry: it’s not in their nature. They only wait.”

Other images succeeded that lost king: the females around small fires, in billowing coats, their lamplike eyes infinitely expressive above their veiled mouths.

“God, look at their wrists,” Mika said. “Like my legs.”

The young played together, young blond ogres, unchildish, but with children’s mad energy: cuffing and wrestling and biting with intent purpose, as though training for some desperate guerrilla combat. The females watched them without seeming to. Whenever a child came to a female, leaping onto her back or into her broad lap, he was suffered patiently; once they saw a female throw her great leg onto her child, pinning it down; the child wriggled happily, unable to free himself, while the female went on boiling something in a battered pot over the fire, moving with careful, wasteless gestures. No one spoke.

“Why don’t they say anything?’ Mika said.

“It’s only humans who talk all the time,” Loren said. “just to hear talk. Maybe the leos don’t need to. Maybe they didn’t inherit that.”

“They look cold.”

“Do you mean cold, emotionless?”

“No. They look like they’re cold .”

And as though he knew that his watchers would have just then come to see that, the mild voice began again. “Like gypsies,” he said, “like all nomads, the leos, instead of adapting their environment, adapt to it. In winter they go where it’s warm. Far south now, other prides have already made winter quarters. For these, though, there will be no move this winter. The borders of this Autonomy are closed to them. They are, technically, all of them, fugitives and criminals. Somewhere in these mountains are Federal agents, searching for them; if they find them, they will be shot on sight. They aren’t human. Due process need not be extended to them. They probably won’t be found, but it hardly matters. If they can’t move out of these snow-choked mountains, most of them will starve before game is again plentiful or huntable. This isn’t strange; far from our eyes, millions of nonhumans starve every winter.”

In half-darkness, the pride clustered around the embers of a fire and the weird orange glow of a cell heater. Some ate, with deliberate slowness, small pieces of something: dried flesh. In their great coats and plated muscle it was hard to see that any were starving. But there: held close in the arms of one huge female was a pale, desiccated child — no, it wasn’t a child; she appeared a child within the leo’s arms, but it was a human woman, still, dark-eyed: unfrightened, but seeming immensely vulnerable among these big beasts.

The image changed. A blond, beardless man, looking out at them, his chapped hands slowly rubbing each other. “We will starve with them,” he said, his mild, uninflected voice unchanged in this enormous statement. “They are what is called ‘hardy,’ which only means they take a long time to die. They have strength; they may survive. We are humans, and not hardy. There’s nothing we can do for them. Soon, I suppose, we’ll only be a burden to them. I don’t think they’ll kill us, though I think it’s within their right, When we’re dead, we will certainly be eaten.”

Again they saw the childlike girl within the leo’s great protecting arms.

“We made these beasts,” the voice said. “Out of our endless ingenuity and pride we created them. It’s only a genetic accident that they are better than we are: stronger, simpler, wiser. Maybe that was so with the blue whale too, which we destroyed, and the gorilla. It doesn’t matter; for when these beasts are gone, eliminated, like the whale, they won’t be a reproach to our littleness and meanness anymore.”

The lost king appeared again, with his gun, the same image, the same awesome repose.

“Erase this tape,” the voice said gently. “Destroy it. Destroy the evidence. I warn you.”

The king remained.

When the tape had run out, the screen flickered emptily. The three humans huddled in their chair together before the meaningless static glow, and said nothing.

(Far off, in the cluttered offices of Genesis Section, Bree Landseer too sat silent, shocked, motionless before a screen; Emma Roth’s large arm was around her, but Emma could say nothing, too full of the bitterest shame and most sinful horror she had ever felt. She, she alone, had brought this about; she had opened the doors to the hunters, the killers, the voracious — not the leos, no, but the gunmen in black coats, the spoilers, the Devil. She had delivered Meric and those beasts into the hands of the Devil. She couldn’t weep; she only held Bree, unable to offer comfort, knowing that for this sin she could not now ever see the face of God.)

“It’s not right,” Sten said. “It’s not fair. It’s not even legal.”

“Well,” Loren said. “We don’t really know the whole story. We didn’t even see the whole tape.”

Sten walked back and forth across the communications room. The screen’s voiceless note had changed to an inscrutable hum, and dim letters said TRANSMISSION DISCONTINUED.

“We could help,” Sten said.

“Help how?” Loren said.

“We could call Nashe. Tell her…”

“What? Those are Federal agents, he said.”

“We could tell her we protest. We could tell everybody. The Fed. I’ll call.”

“No, you won’t.”

Читать дальше