Withdraw: that was what Candy had preached (only not preached, he was incapable of preaching, but he made himself understood, even as Meric’s show did). You have done enough damage to the earth and to yourselves. Your immense, battling ingenuity: turn it inward, make yourselves scarce, you can do that. Leave the earth alone: all its miracles happen when you’re not looking. Build a mountain and you can all be troll-kings. The earth will blossom in thanks for it.

A half century and more had passed since Candy’s death, but there was as yet only one of the thousand mountains, or badger setts, or coral reefs that Candy had imagined men withdrawing into for the earth’s sake and for their own salvation. The building of that one had been the greatest labor since the cathedrals; was a cathedral; was its own god, though every year Jesus grew stronger there.

All the world’s miracles: Meric had combed the patronizing nature-vaudevilles of the last century and culled from them images of undiluted wonder. There was never a time that Bree didn’t weep when from the laboring womb of an antelope, standing with legs apart, trembling, there appeared the struggling, fragile foreleg of its child, then its defenseless head, eyes huge and wide with exhaustion and sentience, and the voice, as though carried on a steady wind of compassion and wisdom, whispered only: “Pity, like a naked newborn babe,” and Bree renewed her vows, as they all silently did, that she would never, never consciously hurt any living thing the earth had made.

Riding upward on the straining elevators, Bree felt that the taint of uncleanness was gone, washed away, maybe, by the sweet tears she had shed. She felt a great, general affection for the crowds she rode with; their patience with the phlegmatic elevator, the small jokes they made at it — “very grave it is,” someone said; “Well, gravity is its business,” said another — the nearness and warmth of their bodies, the sense that she was enveloped by their spirits as by breath: all this felt supremely right. What was the word the Bible used? justified. That was what she felt as she rode the great distance to her level: justified.

She and Meric made love later, in the way they had gradually come most to want each other. They lay near each other, almost not touching, and with the least possible contact they helped each other, with what seemed infinite slowness, to completion, every touch, even of a fingertip, made an event by being long withheld, They knew each other’s bodies so well now, after many years, since they were children, that they could almost forget what they did, and make a kind of drunkenness or dream between them; other times, as this time, it was a peace: it suspended them together in some cool flame where each nearly forgot the other, feeling only the long, retarded, rearising, again retarded, and at last inevitable arrival, given to each in a vacuum as though by a god.

Sleep was only a gift of the same god’s left hand after these nearly motionless exertions; Bree was asleep before she took her hand from Meric. But, much as he expected sleep, Meric lay awake, surprised to feel dissatisfaction. He lay beside Bree a long time. Then he rose; she made a motion, and he thought she might wake, but she only, as though under water, rolled slowly to her side and composed herself otherwise, in a contentment that for some reason lit a small flame of rage in him.

What’s wrong with me?

He went out onto the terrace, his body enveloped suddenly in wind, cold and sage-odorous. The immensity of night above and below him, the nearness of the sickle moon, and the great distance of the earth were alike claustrophobic, and how could that be?

Far off, miles perhaps, he could just see for a moment a tiny, clouded orange spark. A fire lit on the plains. Where no fire was ever to be lit again. For some reason, his heart leapt at that thought.

In the mornings, Meric moved comfortably in seas of people going from nightwork or to daywork, coming from a thousand meetings and masses, many of them badged alike or wearing tokens of sodalities or work groups or carrying the tools of trades. Most wore Blue. Some, like himself, were solitary. Not seas of people, then, but people in a sea: a coral reef, dense with different populations, politely crossing one another’s paths without crossing one another’s purposes. He went down fifty levels; it took most of an hour.

“Two or three things we know,” Emma Roth told him as she made tea for them on a tiny burner. “We know they’re not citizens of anywhere, not legally.

So maybe none of the noninfringement treaties we have with other governments applies to them.”

“Not even the Federal?”

“It’s all men that are created equal,” Emma said. “Anyway, what can the Federal do? Send in some thugs to shoot them? That seems to be all they know how to do these days.”

“What else do we know?”

“Where they are, or were yesterday.” She was no geographer; the maps she had pinned to the wall were old paper ones, survey maps with many corrections.

“Here.” She made a small mark with delible pencil. Meric thought suddenly that after all no mark she could make would be small enough; it would blanket them vastly.

“We know they’re all one family.”

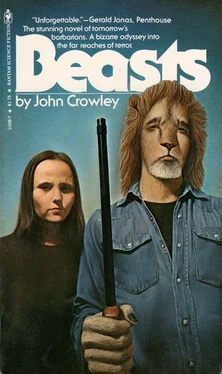

“Pride,” Meric said.

Emma regarded him, a strange level look in her hooded gray eyes. “They’re not lions, Meric. Not really. Don’t forget that.” She lit a cigarette, though the nearly extinguished stub of another lay near her in an ashtray. Smoking was perhaps Emma’s only vice; she indulged it continuously and steadily, as though to insult her own virtue, as a leavening. Almost nobody Meric knew smoked; Emma was always being criticized for it, subtly or openly, by people who didn’t know her. “Well,” she’d say, her voice gravelly with years of it, “I’ve got so much punishment stored up in hell for me that one more sin won’t matter. Besides” — it was a tenet of the cheerful religion she practiced — “what’s all this fear of sin? If God made hell, it must be heaven in disguise.”

Meric returned to the recorder he was trying to fix. It was at least thirty years old and incompatible with most of his other equipment, and it broke or rather gave out in senile exhaustion frequently. But he could make it do. “Are they, what do you call it, poaching?”

“Don’t know.”

“Somebody ought to find out.” With an odd, inappropriate sense that he was tattling, he said: “I saw a fire last night.”

“A lot of people did. I’ve had pneumos about it all day.” With comic exactness, the tube at her side made its hiccup, and she extracted the worn, yellowed-plastic container. She read the message, squinting one eye against the smoke rising from her cigarette, and nodded.

“It’s from the ranger station,” she said. “They are poaching.” She sighed, and wiped her hands on her coat of Blue as though the message had stained them. “Dead deer have been found.”

Meric saw her distress, and thought: there are nearly a hundred thousand of us; there can’t be more than a dozen of them. There are a thousand square miles out there. Yet he could see in Emma the same fear that he sensed in Bree, and in himself. Who were they that they could rouse the Mountain this way?

“Monsters,” Emma said, as though answering.

“Listen,” he said. “We should know more. I don’t mean just you and me. Everybody. We should… I’ll tell you what. I’ll go out there, with the H5 and some discs, and get some information. Something we can all look at.”

“It wouldn’t do any good. They’re poaching. What else do we need to know?”

“Emma,” he said. “What’s wrong with you? Wolves aren’t poachers. Hawks aren’t poachers. You’re losing your perspective.”

Читать дальше