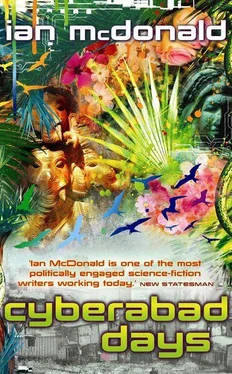

Ian McDonald - Cyberabad Days

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ian McDonald - Cyberabad Days» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2009, ISBN: 2009, Издательство: Gollancz, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Cyberabad Days

- Автор:

- Издательство:Gollancz

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-1-591-02699-0

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Cyberabad Days: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Cyberabad Days»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

); a new, muscular superpower in an age of artificial intelligences, climate-change induced drought, strange new genders, and genetically improved children.

Cyberabad Days — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Cyberabad Days», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘It’s defeatist? It doesn’t take your superhuman intellect to work out that there are no good solutions for this.’

I turned a chair around and perched on it, hands folded on the back, my chin resting on them.

‘What is it you still need to achieve?’

Two laughs, one from the speakers, the other a phlegmy gurgle from the labouring throat.

‘Tell me, do you believe in reincarnation?’

‘Don’t we all? We’re Indian, that’s what we’re about.’

‘No, but really. The transmigration of the soul?’

‘What exactly are you doing?’ No sooner had I asked the question than I had raced to the terrible conclusion. ‘The Eye of Shiva?’

‘Is that what you call it? Good name. Keeping me ticking over is the least part of what this machine does. It’s mostly processing and memory. A little bit of me goes into it, every second.’

Uploaded consciousness, the illusion of immortality, endless reincarnation as pure information. The wan, bodiless theology of post-humanity. I had written about it in my Nation articles, made my soapi families face it and discover its false promises. Here it was now in too too much flesh, in my own real-world soap, my own father.

‘You still die,’ I said.

‘This will die.’

‘This is you.’

‘There is no physical part of me today that was here ten years ago. Every atom in me is different, but I still think I’m me. I endure. I remember being that other physical body. There’s continuity. If I had chosen to copy myself like some folder of files, yes, certainly I would go down into that dark valley from which there is no return. But maybe, maybe, if I extend myself, if I move myself memory by memory, little by little, maybe death will be no different from trimming a toenail.’

There could never be silence in a room so full of the sounds of medicine, but there were no words.

‘Why did you call me here?’

‘So you would know. So you might give me your blessing. To kiss me, because I’m scared, son, I’m so scared. No one’s ever done this before. It’s one shot into the dark, What if I’ve made a mistake, what if I’ve fooled myself? Oh please kiss me and tell me it will be all right.’

I went to the bed. I worked my careful way between the tubes and the lines and wires. I hugged the pile of sun-starved flesh to me. I kissed my father’s lips and as I did my lips formed the silent words, I am now and always must be Shiv’s enemy but if there is anything of you left in there, if you can make anything out of the vibrations of my lips on yours, then give me a sign.

I stood up and said, ‘I love you, Dad.’

‘I love you, son.’

The lips didn’t move, the fingers didn’t lift, the eyes just looked and looked and filled up with tears. He swam my mother to safety on an upturned desk. No. That was someone else.

My father died two months later. My father entered cybernetic nirvana two months later. Either way, I had turned my back once again on Great Delhi and walked out of the world of humans and aeais alike.

The morning of the white horse

What? You expected a hero? I walked away, yes. What should I have done, run around shooting like filmi star? And who should I have shot? The villain? Who is the villain here? Shiv? No doubt he could have provided you with a great death scene, like the very best black-moustached Bollywood baddies do, but he is no villain. He is a businessman, pure and simple. A businessman with a product that has changed every part of our world completely and forever. But if I were to shoot him nothing would change. You cannot shoot cybernetics or nanotechnology; economics stubbornly refuses to give you an extended five-minute crawling death-scene, eyes wide with incomprehension at how its brilliant plans could all have ended like this. There are no villains in the real world – real worlds , I suppose we must say now – and very few heroes. Certainly not ball-less heroes. For after all, that’s the quintessence of a hero. He has balls.

No, I did what any sensible Desi-boy would do. I put my head down and survived. In India we leave the heroics to those with the resources to play that game: the gods and the semigods of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Let them cross the universes in three steps and battle demon armies. Leave us the important stuff like making money, protecting our families, surviving. It’s what we’ve done through history, through invasion and princely war, through Aryans and Mughals and British: put our heads down, carried on and little by little survived, seduced, assimilated and in the end conquered. It is what will bring us through this dark Age of Kali. India endures. India is her people and we are all only, ultimately the heroes of our own lives. There is only one hero’s journey and that leads from the birth-slap to the burningghat. We are a billion and half heroes. Who can defeat that? So, will I yet be the hero of my own long life? We shall see.

After my father’s death I wandered for decades. There was nothing for me in Delhi. I had a Buddhist’s non-attachment though my wandering was far from the spiritual search of my time as a sadhu. The world was all too rapidly catching up my put-upon characters of Town and Country . For the first few years I filed increasingly sporadic articles with Gupshup . But the truth was that everyone now was the Voras and the Deshmukhs and the Hirandanis. The series twittered into nothingness, plotlines left dangling, family drama suspended. No one really noticed. They were living that world for real now. And my sense reported the incredible revolution in a richness and detail you cannot begin to imagine. In Kerala, in Assam, in the beach-bar at Goa or the game park in Madhya Pradesh, in the out-of-the-way places I chose to live, it was at a remove and thus comprehensible. In Delhi it would have been overwhelming. Sarasvati kept me updated with calls and emails. She had so far resisted the Eye of Shiva, and the thrilling instantaneousness and intimacy, and subtler death of privacy, of direct thought-to-thought communication. Shiv’s Third Revolution had given firmness and vision to her gadfly career. Sarasvati had chosen and set herself among the underclass. I took some small pleasure from the television and online pundits saying that maybe that old fart Shakyamuni had been right in those terrible populist potboilers in Gupshup , and the blow of technology had cracked India, all India, that great diamond of land, into two nations, the fast and slow, the wired and the wire-less, the connected and the unconnected. The haves and the have-nots. Sarasvati told me of a moneyed class soaring so fast into the universal-computing future they were almost red-shifted, and of the eternal poor, sharing the same space but invisible in the always-on, always-communicating world of the connected. Shadows and dust. Two nations; India – that British name for this congeries of ethnicities and languages and histories, and Bharat, the ancient, atavistic, divine land.

Only with distance could I attain the perspective to see this time of changes as a whole. Only by removing myself from them could I begin to understand these two nations. India was a place where the visible and the invisible mingled like two rivers flowing into each, holy Yamuna and Ganga Mata, and a third, the invisible, divine Saraswati. Humans and aeais met and mingled freely. Aeais took shapes in human minds, humans became disembodied presences strung out across the global net. The age of magic had returned, those days when people confidently expected to meet djinns in the streets of Delhi and routinely consulted demons for advice. India was located as much inside the mind and the imagination as between the Himalayas and the sea or in the shining web of communications, more complex and connected and subtle than any human brain, cast across this subcontinent.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Cyberabad Days»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Cyberabad Days» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Cyberabad Days» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.