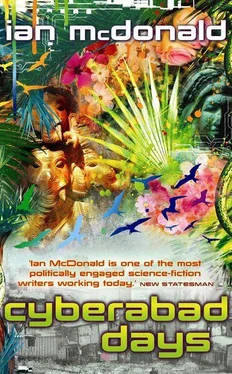

Ian McDonald - Cyberabad Days

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ian McDonald - Cyberabad Days» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2009, ISBN: 2009, Издательство: Gollancz, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Cyberabad Days

- Автор:

- Издательство:Gollancz

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-1-591-02699-0

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Cyberabad Days: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Cyberabad Days»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

); a new, muscular superpower in an age of artificial intelligences, climate-change induced drought, strange new genders, and genetically improved children.

Cyberabad Days — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Cyberabad Days», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I went to a community centre and wrote my first article. I sent it to Suresh Gupta, the editor of Gupshup , that most unashamedly populist of the Delhi’s magazines, which had carried the photographs of my birth and marriage and now, unknowingly, my prophecies of the coming Age of Kali. He rejected it out of hand. I wrote another the next day. It came back with a comment: Interesting subject matter but inaccessible for our readership . I was getting somewhere. I went back and wrote again, long into the night over the pad. I am sure I gained another nickname: the Scribbling Sadhu. Suresh Gupta took that third article, and every article since. What did I write about? I wrote about all the things Shiv had prophesied. I wrote about what they might mean for three Indian families, the Voras, the Dashmukhs and the Hirandanis, village, town and city. I created characters – mothers, fathers, sons and daughters and mad aunties and uncles with dark secrets and long-lost relatives come to call – and told their stories, week upon week, year upon year, and the changes, good and ill, the constant hammerblows of technological revolution wrought upon them. I created my own weekly soap opera; I even dared to call it Town and Country . It was wildly successful. It sold buckets. Suresh Gupta saw his circulation increase by thirty per cent among those Delhi intelligentsia who only saw Gupshup in hair salons and beauty parlours. Questions were asked, who is this pseudonymous ‘Shakyamuni’? We want to interview him, we want to profile him, we want him to appear on Awadh Today , we want an op-ed piece from him, we want him to be an adviser on this project, that think tank, we want him to open a supermarket. Suresh Gupta fielded all such inquiries with the ease of a professional square leg. There were others questions, ones I overheard at train stations and phatphat lines, in supermarket queues and at bazaars, at parties and family get-togethers: What does it mean for us?

I kept travelling, kept walking, immersing myself in the village and small town. I kept writing my little future-soap, sending off my articles from a cellpoint here, a village netlink there. I watched for the Eye of Shiva. It was several months between the first and second, down in a business park in Madhya Pradesh. I saw them steadily after that, but never many; then, at the turn of 2049 to 2050, like a desert blooming after rain, they were everywhere.

I was walking down through the flat dreary country south of the Nepalese border to Varanasi developing my thoughts on evolution, Darwinian and post-Darwinian and the essential unknowability of singularities when I picked up the message from Sarasvati, my first in two weeks of loitering from village to village. At once I thumbed to Varanasi and booked the first shatabdi to Delhi. My natty dreads, my long nails, the dirt and sacred ash of months on the road went down the pan in the first class lounge. By the time the Vishwanath Express drew into the stupendous nano-diamond cocoon of New Delhi Central I was dressed and groomed, a smart, confident young Delhiwallah, a highly eligible teenager. Sarasvati picked me up in her truck. It was an old battered white Tata without autodrive or onboard or even a functioning air-conditioning system. New Delhi Women’s Refuge was painted on the side in blue. I had followed her career – or rather her careers- while I was running the country. Worthiness attracted her; had she been a Westerner and not a Delhi girl I would have called it guilt at the privilege of her birth. Theatre manager here, urban farming collective there, donkey sanctuary somewhere else, dam protest way way down there . She had derided me: deep down at the grass roots was where the real work was done. People work. And who will provide the water for those grass roots? I would answer. It had only taken our brother’s vision of the end of the Age of Kali for me to come round to her philosophy.

She looked older than the years I had spent wandering, as if those my youthfulness belied had been added to hers by some karma. She drove like a terrorist. Or maybe it was that I hadn’t travelled in a car, in a collapsing Tata pick-up, in a city, in Delhi… No, she drove like a terrorist.

‘You should have told me earlier.’

‘He didn’t want to. He wants to be in control if it.’

‘What is it exactly?’

‘Huntingdon’s.’

‘Can they do anything?’

‘They never could. They still can’t.’

Sarasvati blared her way through the scrimmage of traffic wheeling about the Parliament Street roundabout. The Shaivites still defended their temple, tridents upheld, foreheads painted with the true tilak of Shiva, the three white horizontal stripes. I had seen that other mark on the forehead of almost every man and woman on the street. Sarasvati was pure.

‘He would have known whenever he had the genetic checks when I was conceived,’ I said. ‘He never said.’

‘Maybe it was enough for him to know that you could never develop it.’

Dadaji had two nurses and they were kind, Nimki and Papadi he called them. They were young Nepalis, very demure and well-mannered, quiet spoken and pretty. They monitored him and checked his oxygen and emptied his colostomy bag and moved him around in his bed to prevent sores and cleared away the seepage and crusting around the many tubes that ran into his body. I felt they loved him after a fashion.

Sarasvati waited outside in the garden. She hated seeing Dad this way, but I think there was a deeper distaste, not merely of what he had become, but of what he was becoming.

Always a chubby man, Tushar Nariman had grown fat since immobility had been forced on him. The room was on the ground floor and opened out onto sun-scorched lawns. Drought-browned trees screened off the vulgarity of the street. It was exercise for the soul if not the body. The neurological degeneration was much more advanced than I had guessed.

My father was big, bloated and pale but the machine overshadowed him. I saw it like a mantis, all arms and probes and manipulators, hooked into him through a dozen incisions and valves. Gandhi it was who considered all surgery violence to the body. It monitored him through sensory needles pinned all over his body like radical acupuncture and, I did not doubt, through the red Eye of Shiva on his forehead. It let him blink and it let him swallow, it let him breathe and when my father spoke, it did his speaking for him. His lips did not move. His voice came from wall-mounted speakers, which made him sound uncannily divine. Had I been hooked into a third eye, he would have spoken directly into my head like telepathy.

‘You’re looking good.’

‘I’m doing a lot of walking.’

‘I’ve missed you on the news. I liked you moving and shaking. It’s what we made you for.’

‘You made me too intelligent. Super-success is no life. It would never have made me happy. Let Shiv conquer the world and transform society: the superintelligent will always choose the quiet life.’

‘So what have you been up to, son, since leaving government?’

‘Like I said, walking. Investing in people. Telling stories.’

‘I’d argue with you, I’d call you an ungrateful brat, except Nimki and Papadi here tell me it would kill me. But you are an ungrateful brat. We gave you everything – everything – and you just left it at the side of the road.’ He breathed twice. Every breath was a battle. ‘So, what do you think? Rubbish, isn’t it?’

‘They seem to be looking after you.’

My father rolled his eyes. He seemed in something beyond pain. Only his will kept him alive. Will for what I could not guess.

‘You’ve no idea how tired I am of this.’

‘Don’t talk like that.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Cyberabad Days»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Cyberabad Days» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Cyberabad Days» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.