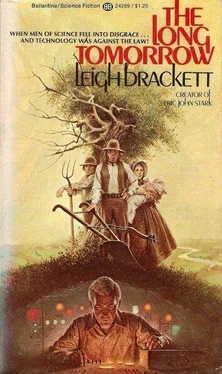

Leigh Brackett

The Long Tomorrow

“No city, no town, no community of more than one thousand people or two hundred buildings to the square mile shall be built or permitted to exist anywhere in the United States of America.”

Constitution of the United States THIRTIETH AMENDMENT

Len Colter sat in the shade under the wall of the horse barn, eating pone and sweet butter and contemplating a sin. He was fourteen years old, and he had lived all of them on the farm at Piper’s Run, where opportunities for real sinning were comfortably few. But now Piper’s Run was more than thirty miles away, and he was having a look at the world, bright with distractions and gaudy with possibilities. He was at the Canfield Fair. And for the first time in his life Len Colter was faced with a major decision.

He was finding it difficult.

“Pa will beat the daylights out of me,” he said, “if he finds out.”

Cousin Esau said, “You scared?” He had turned fifteen just three weeks ago, which meant that he would not have to go to school any more with the children. He was still a long way from being counted among the men, but it was a big step and Len was impressed by it. Esau was taller than Len, and he had dark eyes that glittered and shone all the time like the eyes of an unbroken colt, looking everywhere for something and never quite finding it, perhaps because he did not know yet what it was. His hands were restless and very clever.

“Well?” demanded Esau. “Are you?”

Len would have liked to lie, but he knew Esau would not be fooled for a minute. He squirmed a little, ate the last bite of pone, sucked the butter off his fingers, and said, “Yes.”

“Huh,” said Esau. “I thought you were getting grown-up. You should have still stayed home with the babies this year. Afraid of a licking!”

“I’ve had lickings before,” said Len, “and if you think Pa can’t lay ’em on, you try it some time. And I ain’t even cried the last two years now. Well, not much, anyway.” He brooded, his knees hunched up and his hands crossed on top of them, and his chin on his hands. He was a thin, healthy, rather solemn-faced boy. He wore homespun trousers and sturdy hand-pegged boots, covered thick in dust, and a shirt of coarse-loomed cotton with a narrow neckband and no collar. His hair was a light brown, cut off square above the shoulders and again above the eyes, and on his head he wore a brown flat-crowned hat with a wide brim.

Len’s people were New Mennonites, and they wore brown hats to distinguish themselves from the original Old Mennonites, who wore black ones. Back in the Twentieth Century, only two generations before, there had been just the Old Mennonites and Amish, and only a few tens of thousands of them, and they had been regarded as quaint and queer because they held to the old simple handcraft ways and would have no part of cities or machines. But when the cities ended, and men found that in the changed world these of all folk were best fitted to survive, the Mennonites had swiftly multiplied into the millions they now counted.

“No,” said Len slowly, “it’s not the licking I’m scared of. It’s Pa. You know how he feels about these preachin’s. He forbid me. And Uncle David forbid you. You know how they feel. I don’t think I want Pa mad at me, not that mad.”

“He can’t do no more than lick you,” Esau said.

Len shook his head. “I don’t know.”

“Well, all right. Don’t go, then.”

“You going, for sure?”

“For sure. But I don’t need you.”

Esau leaned back against the wall and appeared to have forgotten Len, who moved the toes of his boots back and forth to make two stubby fans in the dust and continued to brood. The warm air was heavy with the smell of feed and animals, laced through with wood smoke and the fragrances of cooking. There were voices in the air, too, many voices, all blended together into a humming noise. You could think it was like a swarm of bees, or a wind rising and falling in the jack pines, but it was more than that. It was the world talking.

Esau said, “They fall down on the ground and scream and roll.”

Len breathed deep, and his insides quivered. The fairgrounds stretched away into immensity on all sides, crammed with wagons and carts and sheds and stock and people, and this was the last day. One more night lying under the wagon, wrapped up tight against the September chill, watching the fires burn red and mysterious and wondering about the strangers who slept around them. Tomorrow the wagon would rattle away, back to Piper’s Run, and he would not see such a thing again for another year. Perhaps never. In the midst of life we are in death. Or he might break a leg next year, or Pa might make him stay home like brother James had had to this time, to see to Granma and the stock.

“Women, too,” said Esau.

Len hugged his knees tighter. “How do you know? You never been.”

“I heard.”

“Women,” whispered Len. He shut his eyes, and behind the lids there were pictures of wild preachings such as a New Mennonite never heard, of great smoking fires and vague frenzies and a figure, much resembling Ma in her bonnet and voluminous homespun skirts, lying on the ground and kicking like Baby Esther having a tantrum. Temptation came upon him, and he was lost.

He stood up, looking down at Esau. He said, “I’ll go.”

“Ah,” said Esau. He got up too. He held out his hand, and Len shook it. They nodded at each other and grinned. Len’s heart was pounding and he had a guilty feeling as though Pa stood right behind him listening to every word, but there was an exhilaration in this, too. There was a denial of authority, an assertion of self, a sense of being. He felt suddenly that he had grown several inches and broadened out, and that Esau’s eyes showed a new respect.

“When do we go?” he asked.

“After dark, late. You be ready. I’ll let you know.”

The wagons of the Colter brothers were drawn up side by side, so that would not be hard. Len nodded.

“I’ll pretend like I’m asleep, but I won’t be.”

“Better not,” said Esau. His grip tightened, enough to squeeze Len’s knuckles together so he’d remember. “Just don’t let on about this, Lennie.”

“Ow,” said Len, and stuck his lip out angrily. “What do you think I am, a baby?”

Esau grinned, lapsing into the easy comradeship that is becoming between men. “ ’Course not. That’s settled, then. Let’s go look over the horses again. I might want to give my dad some advice about that black mare he’s thinking of trading for.”

They walked together along the side of the horse barn. It was the biggest barn Len had ever seen, four or five times as long as the one at home. The old siding had been patched a good bit, and it was all weathered now to an even gray, but here and there where the original wood was projected you could still see a smudge of red paint. Len looked at it, and then he paused and looked around the fairground, screwing up his eyes so that everything danced and quivered.

“What you doing now?” demanded Esau impatiently.

“Trying to see.”

“Well, you can’t see with your eyes shut. Anyway, what do you mean, trying to see?”

“How the buildings looked when they were all painted like Gran said. Remember? When she was a little girl.”

“Yeah,” said Esau. “Some red, some white. They must have been something.” He squinted his eyes up too. The sheds and the buildings blurred, but remained unpainted.

“Anyway,” said Len stoutly, giving up, “I bet they never had a fair as big as this one before, ever.”

“What are you talking about?” Esau said. “Why, Gran said there was a million people here, and a million of those automobiles or cars or whatever you called them, all lined up in rows as far as you could see, with the sun just blazing on the shiny parts. A million of ’em!”

Читать дальше