“The Great Wall of Pork,” says Jimmy. “The Bacon Brigade. The Hoplites of Ham.”

“Hoplites?” says Toby.

“It was a Greek thing,” says Jimmy. “Citizens’ army type of arrangement. A wall of interlocked shields. I read it in a book.” He’s a little short of breath.

“Maybe it’s an honour guard,” says Toby. “Are you okay?”

“These things make me nervous,” says Jimmy. “How do we know they aren’t leading us astray so they can ambush us and gobble our giblets?”

“We don’t know that,” says Toby. “But I’d say the odds are against it. They’ve already had the opportunity.”

“Occam’s razor,” says Jimmy. He coughs.

“Pardon?” says Toby.

“It was a Crake thing,” says Jimmy sadly. “Given two possibilities, you take the simplest. Crake would have said ‘the most elegant.’ The prick.”

“Who was Occam?” says Toby. Is that a slight limp?

“Some kind of a monk,” says Jimmy. “Or bishop. Or maybe a smart pig. Occ Ham.” He laughs. “Sorry. Bad joke.”

They walk on for a block or two in silence. Then Jimmy says, “Sliding down the razor blade of life.”

“Excuse me?” Toby says. She’d like to feel his forehead. Is he running a temperature?

“It’s an old saying,” says Jimmy. “It means you’re on the edge. Plus, you may get your nuts sliced off.” He’s limping more visibly now.

“Is your foot all right?” Toby asks. No answer: he stumps doggedly onward. “Maybe you should go back,” she says.

“No fucking way,” says Jimmy.

The street ahead is blocked by the rubble from a partially fallen condo. There’s been a fire in it — most likely caused by an electrical short, says Zeb, who has halted the march while the scouts reconnoitre a detour. The smell of burning is still in the air. The Pigoons don’t like it: several of them snort.

Jimmy sits down on the ground.

“What?” says Zeb to Toby.

“His foot again,” says Toby. “Or something.”

“So, we need to send him back to the Spa.”

“He won’t go,” says Toby.

Jimmy’s five Pigoons are snuffling at him, but from a respectful distance. One of them moves forward to sniff his foot. Now two of them nudge him, one on either arm.

“Get away!” says Jimmy. “What do they want?”

“Blackbeard, please,” says Toby, beckoning him over. He huddles with the Pigoons. There’s a silent interchange, followed by a few notes of music.

“Snowman-the-Jimmy must ride,” says Blackbeard. “They say his …” There’s a word Toby can’t decipher, that sounds like a grunt and a rumble. “They say that part of him is strong. In the middle he is strong, but his feet are weak. They will carry him.”

One of the Pigoons steps forward, not the fattest. She lowers herself beside Jimmy.

“They want me to do what?” says Jimmy.

“Please, Oh Snowman-the-Jimmy,” says Blackbeard. “They say you must lie down on the back and hold on to the ears. Two others will go beside you to keep you from falling off.”

“This is dumb,” says Jimmy. “I’ll slide off!”

“That’s your only option,” says Zeb. “Catch a ride, or else you stay here.”

Once Jimmy is in position, Zeb says, “Got any of that rope? It might help a bit.”

Jimmy is tied onto the Pigoon like a parcel, and they all set off once more. “So, its name is Dancer, or Prancer, or what?” says Jimmy. “Think I should pat it?”

“Please, Oh Snowman-the-Jimmy, thank you,” says Blackbeard. “The Pig Ones are telling me that a scratching behind the ears is a good thing.”

When reciting the story in later years, Toby liked to say that the Pigoon carrying Snowman-the-Jimmy flew like the wind. It was the sort of thing that should be said of a fallen comrade-in-arms, and especially one that performed such an important service — a service that resulted, not incidentally, in the saving of Toby’s own life. For if Snowman-the-Jimmy had not been transported by the Pigoon, would Toby be sitting here among them tonight, wearing the red hat and telling them this story? No, she would not. She would be composting under an elderberry bush, and assuming a different form. A very different form indeed, she would think to herself privately.

So, in her story, the Pigoon in question flew like the wind.

The telling was complicated by the fact that Toby could not pronounce the flying Pigoon’s name in any way that resembled the grunt-heavy original. But nobody in the Craker audience seemed to mind, though they laughed at her a little. The children made up a game in which one of them played the heroic Pigoon flying like the wind, wearing a determined expression, and a smaller one played Snowman-the-Jimmy, also with a determined expression, clinging to its back.

Her back. The Pigoons were not objects. She had to get that right. It was only respectful.

At the time, things are somewhat different. The progress of the Jimmy-porting Pigoon is lumpy, and its back is rounded and slippery. Jimmy bumps up and down, and is in danger of sliding off, first on one side, then on the other. When this happens the flanking Pigoons give him a sharp upward nudge with their snouts, under the armpits, which causes him to yell maniacally because it tickles.

“For fuck’s sake, can’t you get him to shut up?” says Zeb. “We might as well be playing the bagpipes.”

“He can’t help it,” says Toby. “It’s a reflex.”

“If I bonk him on the head, that’ll be a reflex too,” says Zeb.

“They probably know we’re coming,” says Toby. “They may have seen the scouts.”

They’re following the lead of the Pigoons, but it’s Jimmy who provides the verbal guidelines. “We’re still in the pleebs,” he says. “I remember this part.” Then: “We’re coming up to No Man’s Land, cleared buffer zone before the Compounds.”

Then: “Main security perimeter coming up.” After a while: “Over there, CryoJeenyus. Next up, Genie-Gnomes. Look at that fucking light-up genie sign! The solar must still be working.”

Then: “Here comes the biggie. The RejoovenEsense Compound.” Crows on the wall: four, no, five. One crow, sorrow, Pilar used to say; more, and they were protectors, or else tricksters, take your choice. Two of the crows lift off, circle overhead, sizing them up.

The Rejoov gates stand open. Inside, dead houses, dead malls, dead labs, dead everything. Tatters of cloth, derelict solarcars.

“Thank God for the pigs,” says Jimmy. “Without them, needle in a haystack. The place is a labyrinth.”

But the Pigoons are sure of the trail. They trot steadily forward, not hesitating. A corner turned, another corner.

“There it is,” says Jimmy. “Up ahead. The gates of Paradice.”

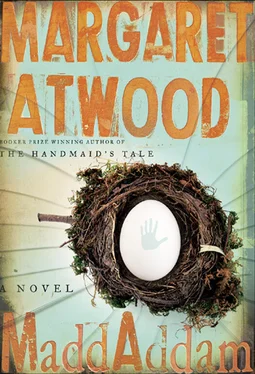

Crake had planned the Paradice Project himself. There was a tight security perimeter around it, in addition to the Rejoov barrier wall. Inside that was a park, a microclimate-modifying planting of mixed tropical splices, tolerant alike to drought and downpour. At the centre of it all was the Paradice dome, climate-controlled, airlocked, an impenetrable eggshell harbouring Crake’s treasure trove, his brave new humans. And at the very centre of the dome he’d placed the artificial ecosystem where the Crakers themselves in all their strange perfection had been brought into being and set to live and breathe.

They reach the perimeter gate, stop to reconnoitre. No one in the gatehouses to either side, according to the Pigoons: their inactive tails and ears are semaphoring as much.

Zeb signals a rest stop: they need to gather their energy. The humans resort to their water bottles and eat half a Joltbar each. The Pigoons have found an avomango tree and are gobbling down the windfalls, the orange ovals pulped by their jaws, the fatty seeds crushed. Fermented sweetness fills the air.

Читать дальше