Marlene Parrish - What Einstein Told His Cook 2

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Marlene Parrish - What Einstein Told His Cook 2» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Издательство: W. W. Norton & Company, Жанр: Кулинария, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:What Einstein Told His Cook 2

- Автор:

- Издательство:W. W. Norton & Company

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

What Einstein Told His Cook 2: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «What Einstein Told His Cook 2»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

What Einstein Told His Cook 2 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «What Einstein Told His Cook 2», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I usually start this recipe in the late afternoon and finish it up the next morning. Do not double the recipe, because the longer cooking time will break down the berries’ pectin and prevent gelling.

About 2¼ pounds strawberries

2 pounds (5 cups) sugar

¼ cup freshly squeezed lemon juice

1.Wash and hull the strawberries. Keep smaller berries whole, but slice larger ones in half.

2.Weigh out 2 pounds strawberries and place them in a large stainless-steel saucepan or heavy preserving kettle. (I use an enameled cast-iron Le Creuset Dutch oven.) Add the sugar and, using a rubber spatula, gently mix it with the strawberries. Let stand for 4 hours, stirring occasionally.

3.Place over medium heat, bring to a boil, add the lemon juice, and cook rapidly for 12 minutes. Cover and let stand in a cool place overnight.

4.In the morning, bring the berry mixture to a boil over high heat, then turn down the heat to low. Remove the berries with a slotted spoon, draining them thoroughly, and spoon them into sterilized half-pint jelly jars, filling them only halfway. Thorough draining is important, because too much liquid in the jars at this stage will thin the jelly.

5.Bring the syrup remaining in the pan to a boil and cook until thickened or until it registers 224°F (107°C) on a candy thermometer. To test if the syrup is ready, dip a soup spoon into the syrup and hold it horizontally over the pan; the syrup should fall from the spoon’s surface in “sheets.”

6.Pour the hot syrup over the berries to fill within ½ inch of the rim. Wipe the rims clean and seal with rubber-rimmed self-sealing tops and metal ring bands. As each jar is filled and sealed, turn it upside down. Allow it to cool in that position.

MAKES SIX HALF-PINTS

BOBBING FOR PUMPKINS

I’m planning a party on Halloween at which there will be bobbing for apples. Must I buy a certain kind, or do all apples float?

Although most apples will float, they can vary somewhat in their aquatic stabilities. Buy samples of a few varieties several days before the party and test them. Then go back to the store and load up on the best floaters. Asking your guests to bob for apples that sink to the bottom would severely compromise your reputation as a caring host.

There is no easy way to predict whether an object will float or sink in water. You just have to try it. On The Late Show with David Letterman , a pair of attractive models drop various objects into a tank of water after Dave and sidekick Paul Shaffer have speculated about whether they will sink or float. Inspired by your question, but unfortunately unable to recruit the models, I decided to play “Will It Float?” on my own.

I went to the supermarket and, to the dismay of the cashier, purchased one each of a variety of fruits and vegetables. (“What’s this?” she often inquired. I answered “Rutabaga” each time, and she was apparently satisfied.) Back home, I filled the kitchen sink with water and, humming my own rendition of Shaffer’s fanfare, dropped them one by one into the water and recorded the results in my laboratory notebook.

Here, then, revealed for the first time in the annals of gastronomic science, are the results of my research. Floaters: apple, banana, lemon, onion, orange, parsnip, Bartlett pear, pomegranate, rutabaga (barely), sweet potato (barely), zucchini. Sinkers: avocado (barely), mango, Bosc pear (barely), potato, cherry tomato.

Almost all of my experimental subjects had difficulty making up their minds as to whether they wanted to sink or float. That’s understandable, because they are all made mostly of water. According to the USDA’s National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference(2003), the edible portions—the flesh—of my subjects range from 73 percent to 95 percent water. They would therefore tend to stay pretty much suspended. In fact, as indicated above, several of them just barely floated or sank.

Note that the USDA’s figures are averages, and my supermarket samples were random individuals. Different varieties and samples of apples and (as I found out) pears may give different results. All in all, though, the odds are good that you’ll find floating apples to bob for.

All of this made me think about the role of density in cooking. Density is a measure of how heavy a substance is for its bulk or volume. It can be expressed as a number of pounds per cubic foot.

Do you remember Archimedes, who jumped out of his bathtub and ran naked and dripping through the streets of Syracuse shouting “Eureka!” (which is Greek for “Who stole my towel”)? Well, Archimedes discovered the principle that governs whether an object will sink or float in a fluid.

Once, when he was a little kid in school, Archimedes’ principal…no, let’s start over.

Archimedes’ Principle states that “a body immersed in a fluid is buoyed up by a force equal to the weight of the fluid displaced.” That statement may be the way we “learned” it in school, but it’s about as illuminating as a firefly wearing an overcoat. How many of us (including our teachers) really understood it? I confess that I never did until I figured it out for myself while fully clothed and dry. Here it is, in a one-paragraph nutshell.

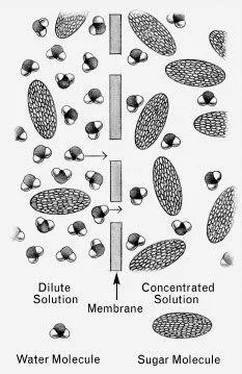

Let’s say we’re bobbing for pumpkins. We’ll completely submerge a 15-inch-diameter pumpkin, which has a volume of one cubic foot, into a big tub of water. One cubic foot of water now has to get out of the way to make room for the pumpkin. That displaced water is necessarily pushed upward—there’s no place else for it to go—so the water level rises. But the water now has a pumpkin-sized hollow in it, and the displaced water wants to flow back down, as is its gravitational habit, and fill it. The only way it can do that is to push the pumpkin back up out of the hollow with whatever force or weight it can muster; for a cubic foot of water, that amount of weight is about 60 pounds. If the one-cubic-foot pumpkin should happen to weigh, say, only 50 pounds, it will be pushed up (buoyed up) by that extra 10 pounds of force from the water. That is, it will float. If that one-cubic-foot pumpkin should happen to weigh 70 pounds, however, it would overcome the 60 pounds of buoyancy and sink.

Conclusion: If an object’s density is less than that of water (which is actually 62.4 pounds per cubic foot), it will float; if its density is greater than that of water, it will sink. (In reality, a 15-inch-diameter pumpkin weighs about 40 pounds and would float.)

What does that mean to us in the kitchen? Here are a couple of examples.

Gnocchi, ravioli, and pierogi will sink at first when you put them into boiling water because they are more dense than the water. But as their starch granules swell in the hot water, their density decreases until they are less dense than water, whereupon they inform you that they are cooked by floating to the surface.

Note that the density of an object can decrease either by the object’s losing weight or by its expanding in volume. When a human object gains both weight and volume, his or her density decreases, because fat is less dense than muscle. Draw your own conclusion.

Another example: In making beignets, or “doughnut holes,” we drop spoonfuls of dough into deep, hot fat. The dough ball is less dense than the oil and therefore floats. But as the portion below the surface browns in the hot oil, it loses water in the form of steam and becomes even less dense. The bottom of the ball is now less dense than the top, and it may actually capsize like a top-heavy boat and proceed to brown its other side.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «What Einstein Told His Cook 2»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «What Einstein Told His Cook 2» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «What Einstein Told His Cook 2» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.