Marlene Parrish - What Einstein Told His Cook 2

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Marlene Parrish - What Einstein Told His Cook 2» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Издательство: W. W. Norton & Company, Жанр: Кулинария, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:What Einstein Told His Cook 2

- Автор:

- Издательство:W. W. Norton & Company

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

What Einstein Told His Cook 2: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «What Einstein Told His Cook 2»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

What Einstein Told His Cook 2 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «What Einstein Told His Cook 2», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But your victory may be as hollow as a pitted olive, because some “black” or “ripe” California olives are picked at the purple stage and then blackened by treatment with alkali, air, or iron compounds (see below) to produce what are called “black-ripe” olives.

The olives on a tree don’t all ripen at the same time, so there is always a mixture of stages to be harvested. Perhaps the biggest problem faced by olive growers is deciding exactly when to harvest for the best yield of the best stage of ripeness for the olives’ intended purpose. Over the years, different countries and regions have developed and maintained their traditional harvesting practices, which contribute to the different flavor characteristics of, for example, Greek and Italian oils and even oils from different regions of Italy.

Historically—and by that I mean for thousands, not hundreds, of years—olives have been harvested by hand, either individually plucked or by means of a sort of comb known as a pettine (which is Italian for, well, “comb”) that is raked along the branches. Alternatively, workers may simply beat the branches with poles to dislodge the fruit. Hand-harvesting is still widely used today, although in Spain, the world’s largest producer of olive oil (a lot of olive oil labeled “Italian” is shipped from Spain and bottled in Italy), I saw heavy, tractor-like machines clamp strangleholds on tree trunks and shake the bejeebers out of them, the ripest and less tenacious olives falling into nets placed on the ground around the tree.

For table use, all olives must be processed in some way; you can’t snack on them right off the tree because they contain a bitter phenolic compound called oleuropein. It must be removed either by microbial fermentation or by soaking in a strongly alkaline solution such as sodium hydroxide (lye).

In California, semi-ripe, greenish-purple olives are soaked in a series of lye solutions of diminishing concentrations, being rinsed and aerated after each soak. This treatment, aided in some cases by the addition of ferrous gluconate, an iron compound, turns the olives thoroughly black, after which they are canned.

So round two must go to your California friend, who may have been referring to this blackening process which, like many California customs, is not practiced anywhere else in the world. In Greece and Turkey, though, they do use a similar process to make fully ripe blackish olives dead black.

OSMOSIS IS A TWO-WAY STREET

I tried making strawberry preserves by boiling the berries first, figuring I could add the sugar later. But all I got was mush. What went wrong?

Osmosis went wrong. It went in the wrong direction.

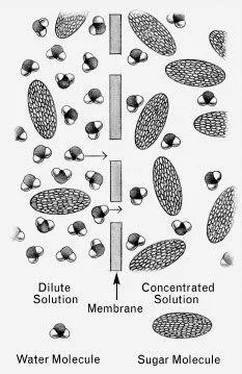

Whenever two water solutions containing different amounts of sugar (for example) are on opposite sides of a plant’s cell wall, water molecules will move spontaneously through the cell wall in the direction of the more concentrated (stronger) solution, making it less concentrated—diluting it. That’s osmosis.

When you cooked the berries in plain water without any sugar, water molecules moved into the cells, where some dissolved sugars already existed, until the cells could hold no more water and burst. Ruptured cells, having lost their crisp cellular structure, are mushy cells.

On the other hand, when you cook a fruit in water with lots of sugar—more sugar than exists inside the cells—water molecules move out of the cells into the external sugar solution. The cells will shrink like deflated balloons, but they won’t burst and their cell walls will still be more or less intact, retaining their toothsome texture. The berries therefore won’t be softened as much by cooking in sugared water as they would be in plain water.

Sugar also has a strengthening effect on the fruit’s cells even when they’re deflated, because it reacts with the proteins in the cell walls.

In Nature, osmosis moves water from a solution of low concentration (of sugar, salt, etc.) through a cell wall or other kind of membrane, into a solution of higher concentration on the other side, thereby diluting or watering down the more concentrated solution. (See “Osmosis” on the following page.) But food producers often want to make a solution more concentrated; that is, to remove water from it—the exact opposite of what osmosis would do.

To accomplish this, they reverse the osmosis process by forcing water out of the dilute solution, through a membrane, and into a more concentrated solution. The process, called reverse osmosis, can require a substantial amount of pressure—as high as 1,000 pounds per square inch—to counteract the natural osmotic pressure and reverse the natural direction of water flow.

For example, the watery whey from cheese making was once considered a waste product and, when discarded, an environmental pollutant. But today, through reverse osmosis, the water is removed and the protein is sold to food manufacturers as the “whey powder” or “milk protein concentrate” that you see in the lists of ingredients in processed foods.

Reverse osmosis is also used to purify water. In this case, the pure water “squeezed out” of the impure water is, of course, the desired product.

Sidebar Science: Osmosis

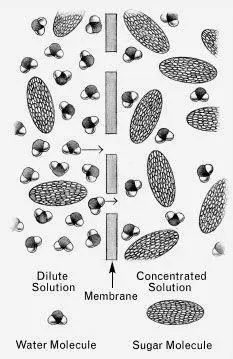

IN A SOLUTIONof sugar in water, there are both sugar molecules and water molecules. If there aren’t many sugar molecules (that is, if the solution is dilute ), the water molecules can freely bombard the walls of their container without much interference from the sugar. If those walls happen to be the walls of a plant cell, which are somewhat permeable to water, many of those water molecules will succeed in passing through to the other side. On the other hand, if a sugar solution is strong ( concentrated ), the sugar molecules will interfere severely, and not as many water molecules will succeed in penetrating the cell wall.

So if we have a dilute solution on one side of a cell wall and a concentrated solution on the other, more water molecules will be flowing from the dilute side to the concentrated side than in the opposite direction, as if there were a net amount of pressure ( osmotic pressure ) forcing them in that direction. They will continue flowing that way until the concentrated solution has been watered down ( diluted ) to the same dilution as the dilute solution.

A dilute sugar solution and a more concentrated sugar solution. Because there are relatively more water molecules in the dilute solution than in the concentrated one, there is a net tendency ( osmotic pressure ) for water molecules to move though the membrane from the dilute solution into the more concentrated solution. (from left to right). *

Strawberry Preserves

In much of the country, locally grown strawberries can be found in farmers’ markets for only a few weeks in late spring. Make the most of this window. Select small, firm but ripe berries in perfect condition. In this method, standing periods alternating with short cooking times yield a preserve with deep red color and fresh flavor.

In making preserves, jams, and jellies, the proportions of the three primary ingredients, fruit pectin, sugar, and acid (lemon juice), are crucial. The gel is formed by the action of the acid on the pectin, so too little pectin or acid will prevent gel formation and you’ll have syrup instead. Too little sugar will make a tough jelly, while too much sugar will make a weak one. Simply put, the ingredients must be measured carefully. That’s why in this recipe the sugar and berries are weighed, rather than measured by bulk.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «What Einstein Told His Cook 2»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «What Einstein Told His Cook 2» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «What Einstein Told His Cook 2» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.