Marlene Parrish - What Einstein Told His Cook 2

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Marlene Parrish - What Einstein Told His Cook 2» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Издательство: W. W. Norton & Company, Жанр: Кулинария, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:What Einstein Told His Cook 2

- Автор:

- Издательство:W. W. Norton & Company

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

What Einstein Told His Cook 2: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «What Einstein Told His Cook 2»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

What Einstein Told His Cook 2 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «What Einstein Told His Cook 2», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Other disaccharides are lactose, found only in the milk of mammals, and maltose, formed when grains are malted—soaked in water until they sprout, such as in making beer and Scotch whisky from barley.

• Oligosaccharides:Oligosaccharides—the name comes from the Greek oligos , meaning few—are carbohydrate molecules made up of fewer than ten monosaccharide units, and are still generally referred to as sugars rather than starches. The three-and four-unit oligosaccharides raffinose and stachyose (note that the names of all sugars end in -ose) are present in beans but are not digestible by humans. Instead, bacteria in our intestines feed on them, showing their ingratitude by producing those gaseous consequences we associate with beans.

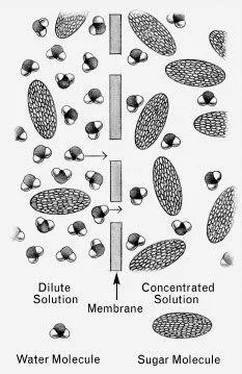

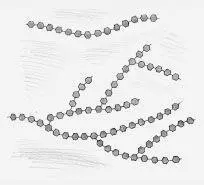

• Polysaccharides:Finally, there are polysaccharides (“many sugars”), also called complex carbohydrates or starches, whose molecules are made up of anywhere from about forty to thousands of glucose units. If the units are joined in long, rather straight chains, they are called amylose starches; if they are joined in a branching, bushy configuration, they are called amylopectin starches. Because of their different molecular shapes, they impart different properties to our starch-containing foods. Most plant starches are mixtures of both amylose and amylopectin.

The two forms of starch molecules. Top: the linear structure of amylose. Bottom: the branched structure of amylopectin. Each hexagon represents one glucose unit.

Other polysaccharides whose names you may have seen on food ingredient labels are dextrins, which are rather large molecular chunks that break off from bigger polysaccharide molecules like dead branches from a tree, when the polysaccharides break down in water.

Too lazy to articulate a four-syllable word, many people today are talking about—and counting—the number of grams of “carbs” in their foods. Carbohydrates—uh, carbs—range upward in molecular size and complexity to thousands of glucose units. If the molecules are big enough, we can’t digest them and they pass right through our alimentary canals without giving us any calories or nutrition. The smaller, digestible carbohydrate molecules—sugars and starches—are loosely referred to as “net carbs” in the proliferating literature of weight-loss dieting, because they’re the ones that are metabolized to yield calories at the rate of 4 calories per gram.

THE FOODIE’S FICTIONARY:Invert sugar—Whoops!

I knocked over the sugar bowl

M*A*S*H

Every time I make mashed potatoes I get different results. Worst of all is when they turn out sticky and gluey. What am I doing wrong?

Mashed potatoes would seem to be the easiest thing in the world to make: just boil ’em and mash ’em, right? But potatoes are mostly starch, and a lot depends on how the starch behaves.

Potato flesh is made up of plant cells. Inside the cells are thousands of starch granules, little round packages in which the plant has stored the molecules of starch that it manufactured during photosynthesis. The starch inside the granules has a gelatinous consistency, so that the granules may be thought of as tiny sacks of glue.

When heated in a moist environment, the granules take on water and swell until some of the sacks disintegrate, spilling their gummy contents. The granules lose their grainy structure and become gelatinized . (See “In a fog about pea soup” on the following page.)

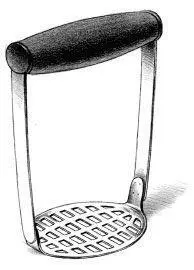

The OXO potato masher. When used with a straight up-and-down motion, it extrudes the potato through its rectangular holes, producing a coarse, non-gluey texture.

But the game isn’t lost yet. If the spilled gelatinous starch remains trapped within the potato’s cells, your spuds are still okay because the potato’s cell structure keeps them firm. But if you then smash the cells open, the gooey starch runs out and gums up the works.

The best masher, in my opinion, is the type that has square or rectangular holes in a flat plate. It extrudes the potato through the holes as a ricer does, rather than crushing it. When mashing, use an up-and-down motion; don’t slide the masher sideways, which would squash open more starch grains. That’s the trouble with those zigzag rod mashers; their round rods squish the potato sideways. And never use a food processor. It is notorious for making gluey potatoes because its sharp blades slash through the swollen starch grains, liberating lots of gluey gel.

Beyond all that, some potatoes are better for mashing than others. Small redskins are waxy and make a waxy mash. Best are the russets, or “Idaho baking potatoes,” and Yukon Golds, whose cell structures give a nice, mealy texture. And the color of the Yukon Golds (see chapter 3) makes your guests think there’s more butter in the mashed potatoes than there is.

How to make mashed potatoes

Cut the potatoes into 1-inch pieces and precook for about 10 minutes at a simmer, not a full boil. That gives the starch grains a chance to swell without rupturing. Then drain the potatoes and let them cool. That allows the swollen starch granules to firm up. When you’re almost ready to mash, simmer the potatoes the rest of the way until they’re barely tender, not mushy. Drain them very well and mash them with a potato masher or ricer. The firmed-up starch granules won’t release their goo as easily as they would have without the precooking and cooling steps.

IN A FOG ABOUT PEA SOUP

Why is it that when I make split pea soup and put the leftovers in the refrigerator, they set up like cement? I then have to add a lot of water and beat it into submission to make it thin enough to eat with a spoon.

Before I answer your question, have you ever wondered why split pea soup has to be made from split peas, rather than whole ones? I know I have. After all, once they’ve been reduced to pottage, who cares whether they were originally intact spheres or, one must presume, had been carefully split in two at the factory by a tribe of elves wielding tiny machetes?

In truth, the split pea is a specific variety of pea whose proper name is field pea, originally native to southwestern Asia and one of the earliest crops cultivated by humans. They have a weak plane or layer that splits apart when the peas are dried. That easy-splitting phenomenon, also found in some minerals, is what mineralogists call cleavage. (Now get your mind back on what I’m talking about!)

All peas are varieties of Pisum sativum . The field pea is to be distinguished from the common garden pea, a.k.a. green pea or English pea, which is usually sold fresh and still in its pod, to be shelled by grandmothers seated at the hearth or, when fresh and young (the peas, not the grandmothers), to be eaten whole, pod and all. The French are particularly fond of their tiny young peas, which they have imaginatively named petits pois, or “little peas.”

Your solidified soup phenomenon is not unique to peas; it is caused by the peas’ abundance of starch, and exactly the same thing will happen in any starchy soup or sauce, such as a gravy that has been thickened with cornstarch or flour and subsequently refrigerated. They, too, will be unyieldingly thick and gelatinous after having been refrigerated.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «What Einstein Told His Cook 2»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «What Einstein Told His Cook 2» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «What Einstein Told His Cook 2» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.